An Open Letter to University Presidents

An Open Letter to University Presidents

10 min read

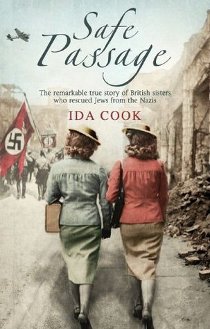

Using their avid opera-going as a cover, the British sisters saved dozens of Jews in Nazi Europe.

They were an eccentric pair: spinster sisters who lived for opera, travelling the world to listen to their favorite performers sing. Yet Ida and Louise Cook harbored a secret. For years, they worked to bring Jews out of Nazi Europe, using their avid opera-going as a cover. In all, the sisters saved the lives of 29 Jews.

Louise Cook was born in 1901 and her sister Ida in 1904. By the time Nazism was ascendant in Europe, the sisters were confirmed middle-aged spinsters, living in their family home in London. Louise was an office worker, Ida a typist and later a prolific writer who published under the name Mary Burchell. Their single passion in life was opera, scrimping and saving to be able to visit the world’s great opera houses.

In 1934, the sisters’ lives changed at one of these operas. A few weeks earlier, Austria’s Chancellor Englebert Dolfus had been murdered by a gang of Nazis. All of Austria was in turmoil, but Ida and Louise cared only for music and travelled to Salzburg for an opera festival where they became friendly with the great Romanian singer Viorica Ursuleac. At the end of the festival, Ursuleac took the sisters by the arm and asked them to look after a dear friend, a certain Frau Mitia Mayer-Lismann, who would be travelling to London soon on a short trip.

Ready for the opera

Ready for the opera

Ida and Louise agreed, and back in London they took Frau Mayer-Lismann around to see the sites. As the women chatted, Frau Mayer-Lismann mentioned that she was Jewish, and was surprised when the clueless sisters said they hadn’t realized. Patiently, Frau Mayer-Lismann explained to Ida and Louise what life was like for Jews in Austria and Germany.

Years later, Ida Cook remembered that conversation as a turning point. “We began to see things more clearly and to see them, to our lasting benefit, through the eyes of an ordinary devoted family like ourselves. By the time the full horror of what was happening in Germany, and later in Austria, reached the newspapers, the whole thing had become almost too fantastic for the ordinary mind to take in,” Ida wrote in her 1950 memoir We Followed our Stars. “It took a war to make people understand what was happening in peacetime, and very many never understood it. To us, the case of the Mayer-Lismanns was curious and shocking, but we did what I suppose most people would have done. We asked, ‘Where did they hope to go? And what could we do to help?’”

As British women living in London, it was difficult indeed to help Austrian and German Jews. Britain restricted the number of Jewish refugees it accepted and the paltry number of refugees it did accept was allowed only under strict conditions. Jewish refugees had to be sponsored by a British citizen and had to produce a large sum of money guaranteeing they wouldn’t be a burden on the state. Because refugees were not allowed to work in Britain, this financial guarantee had to be produced upfront, posing a near-insurmountable burden on many Jews.

Moved by Frau Mayer-Lismann’s descriptions, Ida and Louise began to sponsor refugees. When their money ran out, they encouraged others to help and marshalled resources to provide guarantees to Jewish refugees.

Ida later described their methods. “We began to coordinate the smaller offers of money or hospitality around individual cases, until we had enough money or hospitality to ‘cover’ a case. Then we would persuade some trusting friend or relative to sign the official guarantee form, on the understanding that the guarantee would never be called on because we already had the wherewithal to meet the needs of the case.” Many of the sisters’ friends started cutting back on their daily expenses, walking instead of taking the bus or cutting out cigarettes, for instance, in order to contribute to refugees’ pledge guarantees.

Word soon spread among Jews in Germany and Austria, and Ida and Louise were inundated with requests for help.

Word soon spread among Jews in Germany and Austria, and Ida and Louise were inundated with requests for help. Louise began learning German to better aid the refugees. Every few months, the sisters would travel to Germany to meet with potential refugees, with the pretext of attending operas as cover. In order to evade scrutiny, they travelled through smaller ports, flying from Croydon airport near London into Cologne on a Saturday morning and returning via boat from Holland on Sunday nights. “You never know what you can do until you refuse to take no for an answer,” Ida later explained of their travels.

In Germany, Ida and Louise often worked with Clemens Krauss, the head of the Berlin State Opera and then the Munich Opera House. Krauss was married to the singer Viorica Ursuleac, who’d befriended the Cook sisters years before. Throughout World War II, it was assumed that Clemens Krauss was a passionate Nazi; afterwards it was revealed that he in fact had personally worked to help Jews escape. In the case of the Cook sisters, he provided them cover for their trips. When they announced another visit to Germany, Krauss would send them the details of that weekend’s opera performances so they could gush about seeing their favorite opera to suspicious border guards or other officials.

Ida’s forthright style moved others to action.

Back in Britain, Ida began writing and speaking out publicly about the dangers facing Jews in Europe. Her forthright style moved others to action. Invited to address her first conference about the situation, Ida was dismayed at the dry, academic tone of the speakers. When her turn came, Ida decided to talk about an actual Jew. “He has asked me to save his life. He is under sentence to go back to Buchenwald Concentration Camp - and almost certain death - unless he can be got out of the country in a matter of weeks. I have no guarantee. I have no means of saving him. He must die, unless I can find both - and find them quickly.”

Ida recalls the profoundly uncomfortable silence that followed. Three days later, the conference organizer’s secretary called her. She had been crying nonstop about the Jew Ida had spoken of and she and her husband had decided to sponsor him themselves, saving his life.

In the final years leading up to World War II, Ida and Louise began an even more dangerous activity: having exhausted their own finances to pledge refugees, they began smuggling diamonds and other precious gems that desperate Jews had purchased out of Austria and Germany in order to help pay pledges to resettle in Britain. This carried huge risks: Jews weren’t allowed to bring valuables out of those countries, and the penalties for anyone caught helping them would be severe.

On November 9, hordes of Nazis and Nazi-sympathisers poured into the streets of cities and towns throughout Germany and Austria, burning thousands of synagogues, destroying Jewish businesses, and beating and killing scores of Jews. Thirty thousand Jews were arrested that night. For the world, it became clear just how little Nazis thought the lives of Jews was worth. Just weeks after these pogroms, Ida was asked to travel once more to Germany to help an older Jewish woman get out to safety in Britain.

Ida did so, at enormous risk, and then was presented with a still more dangerous request. A Jew with a visa to Britain needed help raising the financial guarantee they required. They’d spent their entire life savings to purchase a single diamond brooch which would cover the guarantee, but Jews were barred from bringing valuables out of Germany. Would Ida please smuggle this life-saving jewelry into Britain instead? Ida said yes.

She affixed the huge diamond brooch to the front of her cheap sweater. People would assume it was a fake.

When she saw the brooch, Ida was appalled. It was an enormous oblong, glittering with huge diamonds. At the time, Ida was wearing a cheap cardigan from Marks & Spencer. With trembling fingers, she affixed the blazing diamond brooch to the front of her sweater, reasoning that anyone seeing her would assume it was a fake. Her ruse worked, and she returned to England with the brooch still affixed to her cheap outfit.

In the following months, both Ida and Louise repeated this daring ruse time and again, smuggling diamonds and pearls that Jewish refugees had bought with their life savings into England where they were converted into pledges guaranteeing them a safe place to stay. If they were caught, the sisters decided to “do the nervous British spinster act” and behave eccentrically. When an Austrian frontier official questioned Louise’s opulent string of pearls that she was wearing along with her otherwise inexpensive outfit, she acted affronted, exclaiming, “And why not?!’ She frantically ran to a mirror and looked at herself, all the while yelling at the inspector, “What is wrong with my appearance? What were you trying to imply?” until the inspector fled Louise’s crazy act.

The last person Ida and Louise were able to rescue, their 29th, was a 25-year-old Jewish photographer named Lisa Basch. It was 1939 and the sisters’ old friend Frau Mitia Mayer-Lismann was now living safely in Britain. She handed the sisters a list of names and addresses with the words “God bless you and help you” written at the top.

Louise had no more leave from work, so Ida went alone to Frankfurt to the Basch’s family home. It was in ruins, having been searched by the SS. Most of the Basch family had found refuge; only Lisa remained with no place to go. Ida interviewed her, then got to work raising a guarantee, allowing Lisa to find refuge in England.

In 2007, Lisa Basch recalled Ida Cook to Britain’s Daily Telegraph, remembering that Ida had been like a mother to her. Ms. Basch eventually moved to New York, and recalled that every time the Cook sisters visited that city, Lisa “was completely at their service. Wherever they had to go, whomever they wanted to visit, I drove them there. Ida always said to me, ‘You don’t have to repay anything.’ but I wanted to. I was so grateful. I loved her really, and if it hadn’t been for her…”

In 1965, Israel’s Yad Vashem named Ida and Louise Cook Righteous Among the Nations. Ida died in 1986 at the age of 82, and Louise in 1991 at the age of 90. In 2010, they were posthumously honored as “Heroes of the Holocaust” by the British Government.

In 1965, Israel’s Yad Vashem named Ida and Louise Cook Righteous Among the Nations. Ida died in 1986 at the age of 82, and Louise in 1991 at the age of 90. In 2010, they were posthumously honored as “Heroes of the Holocaust” by the British Government.

Donald Rosenfeld, a British film producer, is working on a movie about Ida and Louise Cook, titled The Cooks. “They are huge heroes,” he explains. “This movie is an opportunity to make a global tribute to them.” Mr. Rosenfeld is appealing for anyone with a personal story or connection to Ida and Louise Cook to contact Sovereign Films.

I was wondering if anyone reading this may have the contact information for their estate or relatives. I think this would be an interesting screenplay and would like to talk to them about it.

Thank you.

Regards,