Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

7 min read

Born to a fairly observant Jewish family, Dylan had a decidedly Jewish upbringing.

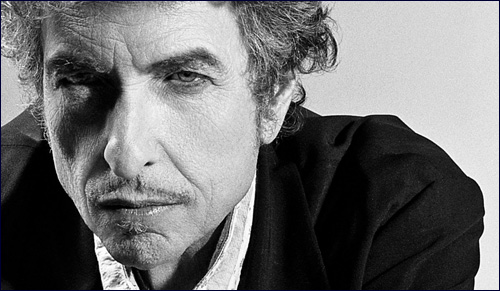

Mazel tov to Bob Dylan on winning the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Unlike the film or comic book industries, pop music has never been particularly Jewish. There have been Jewish managers and behind-the-scenes men like Brian Epstein or Leonard and Marshall Chess, but, on the whole, pop music since the dawn of the rock-and-roll era (roughly 1955 or so) has not exactly been inundated by Jewish talent. There are exceptions, of course, but how much did the Jewishness of, say, Lou Reed or the Clash's Mick Jones really influence their work or, for that matter, their public personas?

Bob grew up in a kosher home and even attended the religious-Zionist summer camp, Camp Herzl.

If you're looking for a particularly Jewish pop musician, however, you needn't actually look much further than arguably the single most influential figure in the history of rock and roll: the one, the only, Bob Dylan. Dylan being Dylan, though, his Jewishness may be present and accounted for, but has also been as complex and as contradictory as everything else about the man.

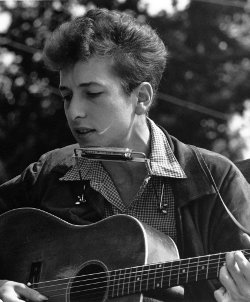

Born Robert Allen Zimmerman (or to give him his Hebrew name: Shabtai Zisl ben Avraham) to, by all accounts, a fairly observant Jewish family, Dylan had a decidedly Jewish upbringing as part of the tight-knit, small Jewish communities of Duluth and Hibbing, Minnesota, growing up in a kosher home and even attending the religious-Zionist summer camp, Camp Herzl.

At least, I think that's the case. It's always been very hard to tell the difference between reality and mythology when it comes to the ever-mercurial Bob Dylan.

At least, I think that's the case. It's always been very hard to tell the difference between reality and mythology when it comes to the ever-mercurial Bob Dylan.

Once he decided to follow in the footsteps of his folk-music heroes Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly and left both his home town and his real name behind. Dylan became increasingly cagey about his personal life and even more so about his origins. Indeed, “cagey” is rather underselling the tall tales and outright lies that Dylan concocted both in his early days as a homeless folk singer, paying his dues in New York's legendary Greenwich Village, and, most especially a few years later, when he was heralded as The Voice of a Generation in the mid-1960s.

Presumably a mixture of self-mythologizing, genuine humility (yes, only Dylan could get away with both), and an apparent love for messing with both the press and his most ardent followers, Dylan went out of his way to make sure that people knew as little about the real Bobby Zimmerman as possible. Over the years, though, the man behind the legend has emerged somewhat and it has become increasingly clear that, not only did he have this very Jewish upbringing, but he never moved quite as far away from his roots as it may appear at first.

While it's true that Dylan's lyrics, especially in his '60s heyday, are often even more (beautifully) oblique than his persona, they sometimes tap into his rich Jewish tradition far more than anything he said in those endless press conferences and interviews. In fact, at the very dawn of his career, while still making routine appearances in the Village, he even played a short snippet of the famous Jewish ditty, Hava Nagila , which has been forever immortalised on the inaugural volume of his Bootleg Series as “Talkin' Hava Nageilah Blues” but introduced on the night as “a foreign song I learned out of Utah”. One wonders what the Mormons thought of that.

While it's true that Dylan's lyrics, especially in his '60s heyday, are often even more (beautifully) oblique than his persona, they sometimes tap into his rich Jewish tradition far more than anything he said in those endless press conferences and interviews. In fact, at the very dawn of his career, while still making routine appearances in the Village, he even played a short snippet of the famous Jewish ditty, Hava Nagila , which has been forever immortalised on the inaugural volume of his Bootleg Series as “Talkin' Hava Nageilah Blues” but introduced on the night as “a foreign song I learned out of Utah”. One wonders what the Mormons thought of that.

Biblical references constantly popped up in his work.

In terms of real songs that he actually wrote, though, Biblical references constantly popped up in his work, but none more so than in three notable tracks from his first and best decade as a working songwriter/performer. The first, the title-track of arguably his best album, Highway 61 Revisited, opens up with a less-than-accurate retelling of the Binding of Isaac. Much more reverently, a section of the Tanach appears again a couple of years later in one of his all-time masterpieces, All Along the Watchtower (obviously best known by Jimi Hendrix's incendiary cover). The song seems to be largely based on a passage from Isaiah 21:1-10 that tells of the fall of Babylon, but whose striking imagery is refashioned by Dylan into something far more obscure and dreamlike – if no less poetic.

Most Jewish of all though is yet another untouchable classic, Forever Young, that adds Jewish prayer to some very on-point Biblical imagery. The song is, by all appearances, an adaptation of the blessing that Jewish parents traditionally give to their children on Friday nights and festivals that was written by Bob for his young son, Jacob (later a musician in his own right and one of five children that Dylan had with his Jewish first wife, Sara). It even opens with a line straight from the Priestly Blessing: “May God bless and keep you always”, and includes an explicit reference to the story of Jacob's dream (“May you build a ladder to the stars and climb on every rung”) which is clearly a reference both to Dylan's son and the originator of this Jewish tradition of blessing one's children, our Patriarch Jacob, himself.

Most Jewish of all though is yet another untouchable classic, Forever Young, that adds Jewish prayer to some very on-point Biblical imagery. The song is, by all appearances, an adaptation of the blessing that Jewish parents traditionally give to their children on Friday nights and festivals that was written by Bob for his young son, Jacob (later a musician in his own right and one of five children that Dylan had with his Jewish first wife, Sara). It even opens with a line straight from the Priestly Blessing: “May God bless and keep you always”, and includes an explicit reference to the story of Jacob's dream (“May you build a ladder to the stars and climb on every rung”) which is clearly a reference both to Dylan's son and the originator of this Jewish tradition of blessing one's children, our Patriarch Jacob, himself.

Of course, all these Jewish references are all well and good but as anyone familiar with Dylan would tell you, there is that whole business with Dylan's brief interest in evangelical Christianity in the late 1970s which, ironically, produced some of his most uninspired music. Even more oddly, it was this turn that would ultimately result in Dylan's Judaism being more explicit than ever.

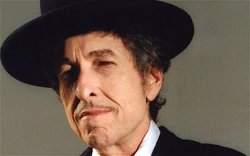

The 1980s saw Dylan becoming increasingly close to the Chabad-Lubavitch movement and the release of by far his most Jewish song ever: Neighborhood Bully. It doesn't exactly rank among his best work, but its lyrics are an impassioned response to critics of both Israel and the Jewish people. The entire song is a thinly veiled commentary on the tendency for some to lay all the world's ills at the foot of this tiny nation and their tiny nation-state (the bully of the title – I assume I don't need to spell out what the “Neighborhood” is), and a proud summation of the Jewish nation's ability to survive everything the world has thrown at us for the last four millennia.

As for his ties to Chabad, they have remained strong throughout the past few decades, despite Dylan's insistence that he has no time for organised religion. He has been spotted at a number of Yom Kippur services in Chabad shuls, has laid tefillin at the Kotel, and has taken part in a number of Chabad telethons.

As for his ties to Chabad, they have remained strong throughout the past few decades, despite Dylan's insistence that he has no time for organised religion. He has been spotted at a number of Yom Kippur services in Chabad shuls, has laid tefillin at the Kotel, and has taken part in a number of Chabad telethons.

Since the early '80s and his public embracing of his Jewish roots, more and more stories have also come out about both Dylan's Jewish ties and his restless, lifelong search for spirituality that sometimes butted heads with the hedonistic rock and roll lifestyle. And yet, for all of his mistrust of organised religion, and for all of his bohemian “freewheeling” nature, there is something about Judaism that has called to him time and time again over the years. In particular, he has been greatly influenced by a number of rabbis, whose openness, warmth, and great emphasis on the spiritual and mystical sides of Judaism, have clearly struck home with the former Mr Zimmerman. In particular, he formed a deep connection with Rabbi Shlomo Freifeld z”l, Rosh HaYeshivah of Yeshivas Shor Yoshuv, when Dylan, along with fellow Jewish bohemian poet Alan Ginsberg, attended a sheva brochas for an old friend at Rabbi Friefeld's yeshiva in New York. So taken was Dylan with both the Rabbi and the Yeshiva that he came very close to actually buying a place near the Yeshiva and was quoted as saying, when visiting Rabbi Friefeld on a particularly cold New York's winter night, “It may be dark and snowy outside, but inside that house, it's so light.”

Alas, he never quite went that far and his Judaism has remained but one (very big) part of an unquestionably complex spiritual identity. But when you consider just how much in-flux the very concept of Jewish identity is in our modern world, there's something profoundly fitting about one of our foremost cultural icons being so “complicatedly Jewish” himself.

Reprinted from Jewish Life magazine, www.jewishlife.co.za, download the free Jewish Life app on iOS and Android

Why are we enthralled when Jews who ignore their spiritual essence and destiny, then use their God-given talents to make it big in the non-Jewish world, deign to throw a few crumbs back at the cosmic destiny they left behind?