We Were the Lucky Ones

We Were the Lucky Ones

14 min read

Left-right, blue-red, rich-poor. With the U.S. elections over, how can the healing begin?

The U.S. presidential election is mercifully over. The billions of TV ads and robocalls have stopped. By all observations the election was a referendum on two vastly different visions for America – issues of economic growth, taxes, social programs, family values, and foreign policy. Vitriol spewed from both sides of the political aisle. Surveys show that the election had a widespread negative impact on interpersonal relationships, spurring heated arguments among family and friends (often on social networking sites like Facebook, where people don't have the polite restraint of facing one another).

What is the root of this polarization? Whatever happened to the credo – as expressed by the Jewish Sages – that "People of good will can reason together and reach a common conclusion"? What can we do to pull together and really listen to one another, to understand the opposing view, and to find common ground?

Working in harmony does not mean we are all identical.

The first step is to correct a misconception about what it means to be working in harmony. Unity does not mean we are all identical, or even that we agree on how to reach our goals. Rather, unity means respecting each individual and appreciating their unique contribution to the whole. Jewish tradition states there are “70 faces to Torah.” Only the most arrogant among us believe they are the exclusive guardians of truth in every facet.

As one friend wrote on Facebook, "Whoever you voted for, there are 50 million people who voted for the other guy. So maybe they're not all crazy, evil or stupid. Maybe there are two rational ways of sizing up what's beneficial for America."

Rather than encouraging political battles, those who care about our future should be working to build consensus.

Herein lies the litmus test. If someone’s actions are creating discord, that’s probably a sign they’re acting out of self-interest. Whereas someone who builds bridges of understanding is most likely acting out of genuine altruistic concern.

So let’s get to the core of the problem. What is driving this polarization?

I believe the answer is two-fold: Power and Profit.

#1 – Political Power

Political leaders have a vested interest in generating party loyalty, calling for a "toeing the line" that discourages independent thinking and polarizes debate. This is due in part to activist groups like the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street, who by nature tend toward more extreme positions than the rest of the population. On top of this is a primary system that forces candidates to appeal to one-half of the electorate – i.e. "play to the base" – thus driving candidates to take more extreme positions than they might truly believe.

With this, we are witnessing the vanishing center of American politics. Ideological separation between Republicans and Democrats is at its highest degree in nearly a century, with party lines accounting for 93 percent of Congressional roll call votes.

Backlash against one centrist signals to other "centrists" to beware.

Connecticut Senator Joseph Lieberman illustrates the challenge of centrism. As a Democrat, Lieberman took conservative positions on many issues - pro-business, criticizing President Clinton's moral behavior, and even supporting the war in Iraq. His views branded him a party traitor, and his near-banishment from the Democratic party (Lieberman successfully won re-election as an independent) signaled to other "centrists" that they'd better beware.

In recent years, the vast majority of those departing from Congress have come from the moderate wings. Intense ideological battles has made it increasingly difficult to achieve political consensus in Washington, fomenting gridlock and dysfunction in Congress, and making life unbearable for those who genuinely seek to problem-solve.

Our leaders have lost the art of compromise, placing the common good above their quest for domination. This scorched-earth partisan politics keeps us from recognizing potential allies; from using our collective intelligence to innovate creative new solutions; and at the very least, from treating each other like decent human beings. What hope does that bring?

#2 – The Media’s Pursuit of Profit

The second cause of polarization is the news media, which has a vested interest in presenting things in stark black-and-white terms. The media's profit margin – i.e. attracting a large audience – is a direct function of stirring controversy and cynically employing hyperbole that stokes and inflames "hot-button" issues.

My book, David & Goliath, addresses a basic question: Exactly who are the media's customers? On one level, it's the general public. But on a deeper level, the media's customers are commercial advertisers, sold a product called "eyeballs." (That's you and me.) That's why the news media is constantly trying to stir controversy. The more compelling the show, the more eyeballs tune in, the more they can charge advertisers, and the greater profit they reap.

Wouldn’t a more responsible media have clarified the parameters of normative debate?

Consider the issue of abortion. Studies show that most Americans favor a nuanced approach – opposing abortion as a convenient method of birth control, yet favoring abortion when the mother’s physical or mental health is at stake. (Read: Abortion in Jewish Law) Yet in the recent campaign, when two Senatorial candidates suggested that rape is not a reasonable cause for abortion, the news media jumped on this to present the abortion issue polarized in all-or-nothing terms. Such a distortion leaves reasonable people flummoxed. Wouldn’t a more responsible media have identified these as “extremist positions,” while clarifying for voters the parameters of normative debate?

In the early days of television, network news operated on the principle of just-the-facts-journalism (think Walter Cronkite). Consumers all had the same choice of three channels, each moderate and centrist. Yet with today’s vast competition on cable TV, coupled with Internet technology, the world of journalism has become irrevocably altered. With so many choices, media outlets have to compete harder for audience share – boosting the level of sensationalism and driving society into greater segregation of like-minded components.

As one pundit wrote, most of us exist in our own political bubbles. With thousands of channels and websites to choose from, we can cherry-pick information that conforms to what we already believe. We tend to stew in our own juices, without benefit of anyone we know well and with whom we disagree – and this makes it almost impossible for us to understand the other side.

As one pundit wrote, most of us exist in our own political bubbles. With thousands of channels and websites to choose from, we can cherry-pick information that conforms to what we already believe. We tend to stew in our own juices, without benefit of anyone we know well and with whom we disagree – and this makes it almost impossible for us to understand the other side.

Gene Weingarten, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist for the Washington Post, recounts that as a "hungry young reporter in the 1970s," he thought of himself as "an invincible crusader for truth and justice." Now, he says, the media is in a "frantic, undignified campaign… [for] attracting more 'eyeballs.'"

Finding Solutions

We must do something to reverse this trend.

Probably the most well-known Hebrew word is shalom, peace. Shalom pervades Jewish life – as the theme of endless poems and songs; used as a greeting for both “hello” and ”goodbye”; and the final word of Judaism’s most important prayers.

Everybody wants peace. Yet how do we achieve it?

Here are three strategies:

(1) Stop All Negativity

During the recent campaign, 78 percent of Americans expressed frustration with the fragmented and strident news media, along with the sickening level of shrill and demonizing attack ads.

Judaism has a stop-gap mechanism to prevent this war of words. The Torah enjoins us not speak negatively of others (Leviticus 19:16). Gossip is a verbal atomic bomb that destroys marriages, businesses, friendships. Even if it's true, that doesn't mean it’s right to say it. The world has enough problems. We don’t need to compound things by breeding resentment.

Judaism has a stop-gap mechanism to prevent this war of words. The Torah enjoins us not speak negatively of others (Leviticus 19:16). Gossip is a verbal atomic bomb that destroys marriages, businesses, friendships. Even if it's true, that doesn't mean it’s right to say it. The world has enough problems. We don’t need to compound things by breeding resentment.

Imagine if our energies were spent working together on areas that transcend partisan politics – energy independence, a healthy economy, a healthy environment, and stopping a nuclear-hungry Iran. Have we forgotten the power of E Pluribus Unum – “Out of many, one” – that appears on all our coins and on the Great Seal of the United States?

(2) Listen Carefully

The two most famous disputants in Talmudic literature are Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai. They argued about almost everything and saw the world from nearly opposite perspectives. For example, Beit Hillel says we should light one Chanukah candle the first night, then add one candle each subsequent night. Beit Shammai argues and says to light 8 candles the first night, decreasing one candle each night.

Jewish law follows Beit Hillel, and the Talmud explains why: In the course of disagreement, Beit Shammai would typically state his own opinion, whereas Beit Hillel would first state the opinion of Beit Shammai – and only then state his own position. This way, Beit Hillel demonstrated a concern not just with being right, but seeking the truth that lied somewhere in between. That is why Jewish law follows Beit Hillel.

We need to train ourselves to take other people’s ideas seriously. The rule is: Communicate and discuss, rather than yell-and-proclaim. If you find yourself getting defensive, interrupting and responding impetuously, that’s a sure sign you’ve become entrenched in a position, closed off to rational debate, and stuck in the realm of “Us versus Them.” At the very least, we should respectfully "agree to disagree."

One way to draw closer is to focus on our mutual needs for tolerance, trust, respect and understanding. Until proven otherwise, presume the other side is sincere. Aish’s list of core values declares: "I trust that others have good intentions, and give them the benefit of doubt by proactively seeking to resolve conflicts."

Growing up I had powerful role models: My father and his best friend would get together and – with vehement intensity – argue politics. Yet somehow it only strengthened their kinship and mutual respect. As Thomas Jefferson said: "I never considered a difference of opinion in politics, in religion, in philosophy, as cause for withdrawing from a friend."

(3) Exposure to the “Other Side”

When it comes to political controversy, it is always beneficial to become exposed to the “other side,” as a way to understand the opposing position.

The Talmud tells of Rebbe Yochanan, a great scholar who for many years had a study partner named Reish Lakish. When Reish Lakish died, Rebbe Yochanan’s students found him a new and brilliant study partner. Yet Rebbe Yochanan became depressed, explaining: “My new study partner is so brilliant that he can cite 24 proofs that I'm correct. But when I studied with Reish Lakish, he showed me 24 proofs that I was wrong. That's what I miss. I don't want someone who will just agree with me; I want a partner who will challenge my position. In this way we will arrive at the truth together.”

The Talmud, in its list of 48 Ways to Wisdom, speaks of Dikduk Chaverim, literally “fine-tuning with friends.” As Rabbi Noah Weinberg always said: "If you persuade me that you're right, I'll join you." With this attitude, we view opposing perspectives not as adversarial, but as a welcome counterbalance to our own. In facilitating a collective intelligence, differences can be assets.

One possible way to achieve this is through programs that encourage creative dialogue. In Israel, initiatives have been launched that bring together diverse groups such as religious and secular, and Arab and Jew. The highest peace, said Rebbe Nachman of Breslov, is peace between opposites.

In America, some have proposed a National Service Program that would force members of the “upper tribe and the lower tribe” to live together, if only for a few years. Hippies working with religious fundamentalists to maintain educational policies friendly to home schooling? Imagine!

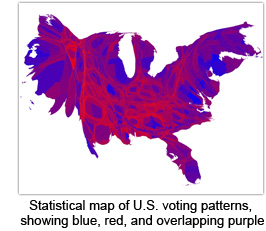

Purple Mountains

This polarization is partly an illusion, generated by those seeking profit and power. American society is blessed with large groups of “rich-and-secular” and “poor-and-religious” citizens whose economic interests and socio-spiritual identities make it difficult to be consistently conservative or liberal on all issues.

True, there have been times of genuine polarization. As a young student at Alexander Hamilton Elementary School, I was well aware of the deathly duel fought by two of America's leading politicians: Hamilton, America's first Secretary of the Treasury, against his arch-rival, Vice-President Aaron Burr. 150 years ago, divisions over slavery led to the bloody Civil War. And a half-century ago, the Sixties exploded into heated battles over civil rights and Vietnam, devolving into a shouting match between: "Make love, not war" versus "America, love it or leave it."

Though such periods are the exception, people still tend to overestimate polarization. In times now remembered as cooperative and cordial, people pegged political disagreements as far more vast than they really were.

Though such periods are the exception, people still tend to overestimate polarization. In times now remembered as cooperative and cordial, people pegged political disagreements as far more vast than they really were.

The same is true today. As Professor John Chambers of the University of Florida observed: "Although we tend to see the world as divided between blue and red, in reality, the world has much greater shades of purple. There is more common ground than we realize."

Yet the danger remains. As politicians and the media highlight the (overstated) homogeneity of each side, this apparent uniformity eventually evolves into actual uniformity by decreasing the exposure of each side to the arguments of the other. We should heed the words of Abraham Lincoln, who knew something about the tragedy of civil discord: "A house divided against itself cannot stand."

Together as One

Why do we so easily tend to fall into this false view of being polarized?

Lack of unity stems from a lack of belief in the single unifying purpose to existence. Most people act out of dichotomy: We regard ourselves at the center of the world, yet nurture a deep innate desire to unite and connect with others.

Are we teammates or competitors? It's like the story of two guys on a boat, and one of them is drilling a hole in the bottom. "What are you doing?!" his friend shouts. "Oh, don't worry," replies the other, "I'm only drilling under my own seat."

As Martin Luther King Jr said, we must learn to live together as brothers or perish together as fools.

One way to get past this is to realize that the distinct units which we call "bodies" are mostly an illusion. On a spiritual level, we are completely united. We intuitively know this to be true. That is how we maintain hope in a better future.

Each of us is one small light, but together we shine bright.

No matter how much we improve ourselves and grow toward our own potential, we cannot change the world by ourselves. Everyone is part of the whole, pieces of an incredible puzzle that together creates a bigger, richer whole. An Israeli folk song says: "Each of us is one small light, but together we shine bright." True, one may be able ram through some legislation and force others to abide by this view. But that is not true change. The only way to achieve unity is through mutual respect.

This is more than just a "nice thing." It is essential to achieving our goals. Dramatic achievement requires solid consensus. When the Jewish people stood at Mount Sinai, they "encamped opposite the mountain" (Exodus 19:2). The Hebrew word for "encamped" (vayichan) appears in the singular form, to emphasize how the entire nation had "a single goal and a singular desire." Any event with such earthshaking consequences could only be possible with unity.

The same is true of our ability to meet the challenges of the 21st century. Barack Obama, at the climax of his election night speech, made an impassioned call for unity, saying we're not "a collection of red states and blue states," but "an American family, one nation."

We need to start acting like it. It begins with each of us, modeling behavior in our communities, and demanding of elected officials that all parties work together to get the job done.

It is the only way forward.