Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

9 min read

Why do so many teenagers rebel against their parents?

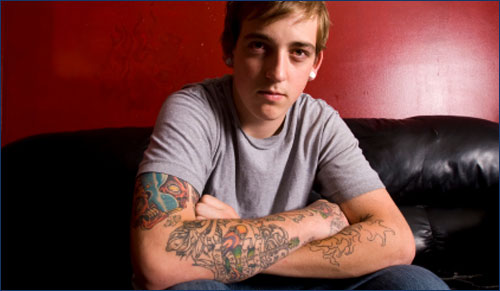

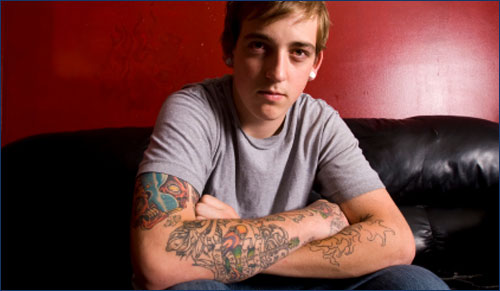

First it was Hebrew school, then it was bar mitzvah lessons, then came the refusal to attend services "even for an hour" on Rosh Hashanah. "I'm not going," Jake said, folding his arms and firmly planting his right foot down on the kitchen step stool. "And no one can make me." And for good measure he added, "I might not even fast at all this Yom Kippur!"

Jake's parents, despite being thoroughly modern in every sense of the word – his father believed in giving his son total freedom in religion though he himself had become more traditional through the years – found to his surprise that he could not digest his son's words. His mother too, a child of traditional parents, was surprised that she felt Jake's words like a stinging slap.

So ingrained is tradition that it comes as a dreadful shock to parents when a boy of bar mitzvah age or close to it, conveys in word or deed: I am not participating. Perhaps it started with a milder refusal, like not wanting to visit Grandpa, but now it is full bloom – he was officially a "refusenik" – but the problem was, he was a dissident on the wrong side, as his parents saw it.

Conversations with the young man went nowhere. He even declared (probably to provoke his father) that he is an "atheist." He cast himself in a noble light. "It would be hypocritical," he protested with no small amount of affectation, "for me to participate in religious rituals that have no meaning for me."

Do I want to please or thwart authority?

His parents are frightened. "Did we raise a non-believer? Sure, the Jewish people have had many a rebel. Many have turned out to be great people, but not our son. Let someone else's son be the next Karl Marx or Leon Trotsky or Sigmund Freud.” Most Jewish parents want to feel they passed on the tradition to their sons and daughters. It is a matter of pride and a measure of their success to link the family with the larger community and the Jewish people.

As a psychotherapist, a great deal of my work has been with parents and children who are in conflict over some aspect of religious observance, but they don’t understand what they’re really fighting about. Sometimes the conflicts are so toxic they even threaten the near-indestructible bonds of family and tribe.

I do not know whether this was always true, but teenagers will rebel. Much of teenage behavior can be understood as a representation of the following conflict: Do I want to please authority or do I want to thwart authority?

This conflict is a reprise of a primitive dance that began at the beginning of life: An infant even a few months old has already learned to please his mother. He might smile at her or make eyes at her, or eat or roll over or do something, anything to please her. Eventually, he learns to please his father and other parent substitutes, his teacher, his synagogue, his country, and beyond. But there is another force in him. He doesn’t want to please at all. He wants to thwart. His father wants him to go to synagogue, his teacher wants him to listen, his mother wants him to put his laundry in the basket or take out the garbage – he’ll come up with every reason why it can’t be done. What’s going on here?

Well, here’s a clue. Everyone knows about the terrible-two’s. When a two year old refuses to put on her shoes – or take them off it may be puzzling to the parent. The famous psychoanalyst Margaret Mahler understood that when the toddler begins to say “no” it may be an expression of separation. She may be saying, “I am not an extension of you. I once was, but I am no longer.” Often, there is a capricious seesaw between “yes and no” without any apparent rhyme or reason to the observer.

This oscillation between yes and no seems to go dormant for a while, but then resurfaces in full bloom in the teenage years (and it echoes throughout life). The child who was once enthusiastic and cooperative suddenly refuses to participate. A once “good” boy wants to say no to the dismay of everyone. Doesn’t he want to follow in the way of his father and his people? He may well want that, but right now his greater pleasure, bizarre at it may seem, is to thwart.

The adult world, with its endless responsibilities and pressures, terrifies him.

Why? "Because he is likely scared out of his wits. The adult world with its endless responsibilities and pressures – the endless chase to make a living, the stumbling at work, the failed business enterprises, the ever-present failures of even the best of fathers, the normal humiliations of life – -it all terrifies him. Will he be able to hack it? Or will he collapse. When a boy derails his father and makes his father stumble, oddly, his fearful tensions are temporarily relieved.

Take the case of Jeremy, for instance. Although Jeremy showed early promise, after his bar mitzvah, he started slacking off. Whereas initially he had ambitions to master the guitar and woodworking, his life at school and at home took on the feel of a listless voyage. He was even seen smoking cigarettes and Heaven knows what else. Everyone was astonished. He was a great kid from a great family. He had a mind as sharp as a blade and aced all the achievement tests in math and science. But what people didn’t realize was that Jeremy's main objective, like many teenagers, was to protect his fragile self and to protect the people around him. Many a young man is plagued with fear of failure. If he is a "good boy," he will fail to be "true to himself"; if he is a "bad boy," he will fail his father and mother. Many are not aware that a teenager's instinct to protect is very strong. He lives in dread of harming everyone, including himself even as he feels he must also protect those around him.

To the adult, Jeremy may appear lazy or even that dreaded word “delinquent.” Actually, Jeremy is hard at work to resolve this crushing conflict – to please his parents or to please himself, if only he knew how. This is a formidable challenge. Given this, it makes sense that his energy would turn toward delay, distraction and a slowing down of his progress in life. His under-performance, for example, his coming late to synagogue, gives him a momentary reprieve from his dilemma. No longer is he "the good boy" with a bright future. He is just a shlep who comes late to synagogue or a ne'er-do-well who smokes. He’s throwing people off the scent of who he is or could possibly be: I’m no prodigy and I'm certainly no good-boy. Don’t have any grand ambitions for me.

Perhaps Freud’s most useful contribution to the world was his insistence that human behavior is likened to the tip of an iceberg. We see only what sticks out above the surface of the water, but we know that the ice is a thousand fathoms deep to the ocean floor. We don’t know why a child or anyone else does things. The reasons are hidden sometimes even to the person himself. All well and good, you may say, but what is a parent to do?

Obviously, there are no hard and fast rules, but a parent has two powerful tools at his disposal: silence and words.

Silence? How can I be silent, one might ask, when my son does such-and-such? "Well one might consider that silence, saying absolutely nothing at all, say in the face of “I’m not going to fast on Yom Kippur,” is a very powerful form of rebuke. "In fact, when dealing with intimates, the seemingly "mildest rebuke, silence, is often the strongest. "What’s more, an added benefit to silence, is that a child learns to quell his urges to defy, to still his impulses, when he sees his father restrain himself from speaking even when provoked. ""

What do you need from me to succeed?

But there’s a time to speak too. "Here’s when: at some point the boy will make contact in a less provocative way. "Perhaps it is later in the week and he needs a ride somewhere and there is light conversation in the car. "The wise parent will wait for just such a propitious moment. Now you can use words, but choose them carefully. "I recommend something along the lines of “You are __ "years old now. "What do you need from me to succeed?” This is a question that when sincerely asked is almost certain to induce love and cooperation. "It is respectful and truthful and speaks directly to the adolescent’s need for both help and independence. It neutralizes the impulse in him to “monkey wrench” and sabotage. "

Nagging words, on the other hand, such as “reminding” a child to study, go to synagogue, do his homework or floss his teeth, is pretty well guaranteed to be pointless at best, and destructive at worst, sowing the seeds for a lifetime of thwarting and undoing.

There’s a story once told of a man who came to the Satmar Rebbe, of blessed memory. He was in a battle with his son. "The man wanted his son to be a rabbi, but the son wanted his father’s help to get to medical school. "The sage told the father: besser tzu zein a rofeh cholim vi a mater assurim. "Better to be someone who heals the sick rather than someone who permits what is forbidden. "

The holy man understood that if the man’s son were to become the “rabbi” of his father’s dreams, the son would still find a way to thwart his father.