Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

9 min read

Believing in God after the Holocaust.

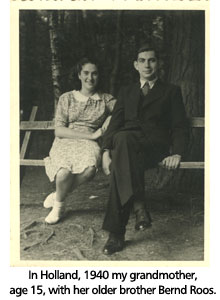

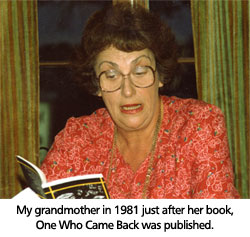

I grew up watching interviews with my Oma on national TV. She may not have been as big as Elie Wiesel, but to me she was larger than life. She was an author and was featured in an Emmy award-winning documentary. She was the most famous person I knew. And she was my Oma.

"Do you still believe in God after the Holocaust?" My Oma’s answer was engraved in my heart.

Every lecture, every interview, every question and answer period included one question. I knew my Oma's answer well; it had been engraved in my mind and in my heart:

"Do you still believe in God after the Holocaust?"

For many the question seemed too controversial, too painful. For Oma, it was simple. I would mouth the words with her: "God is not a babysitter."

For many the question seemed too controversial, too painful. For Oma, it was simple. I would mouth the words with her: "God is not a babysitter."

In my mind, the unasked questions of her listeners screamed for answers. "But where was God when Adolf Hitler (may his name be erased) put in motion the final solution?" "And where was God when your mother and father were taken to the gas chamber?" "And where was God when your brother was brutally shot on a death march just days before liberation?"

But the answer was there too, implanted by my Oma. "God was watching and crying. He was crying for all of his children. The ones that had done wrong and the ones that had been wronged. God runs the world, but He granted His children free will. It is up to them to decide what they choose to do with it. A babysitter is a placeholder for a parent. Their job is to make sure the child remains exactly as they were when the parents left. There's no room for growth because anything remotely dangerous must be stopped before it even begins. Should God have struck each Nazi down with lightning? No, because God is not a babysitter."

As her startled audience recovered from her answer, Oma would continue. "It was not God Who hurt me. People did these things to me. I saw many miracles. Let me read to you from my book..." I would smile as my Oma rifled through the pages of her dog-eared copy of One Who Came Back. I knew most of the book by heart and I knew what story was coming next.

"Another day when four of us were digging stones out of a narrow ditch with our bare hands, my patience was tested again. The stones had to be loaded into a cart, which was pulled by a horse. The German laborer who came with the horse took an instant dislike to me. He harassed and pestered me all day. I paid as little attention to him as possible, which seemed to provoke him even more. Finally he ordered the horse, which was standing above me, to kick me, knock me down and finish me off. I couldn't move, so I started to talk to the horse in a very low voice. I told the horse, in Dutch of course, that he was a nice animal, and I knew he wouldn't hurt me. I just kept talking and talking. Whatever threat the German made, the horse stubbornly stood his ground."

Oma raised her eyes and lowered her reading glasses. "Why would a horse listen to me speaking in a foreign language instead of its owner and master? I saw many miracles like this. God looks out for us. He allows both good and bad to happen. God is not a babysitter."

Visiting Treblinka

From the first time I learned about the program, I wanted to attend the March of the Living. My Oma's experiences were a part of me. I needed to understand, at least in part, what she went through. I don't know what I expected from the trip, but through Majdanek, Auschwitz and Birkenau I clutched my Oma's book hoping to gain strength by osmosis from her words. Even the religious members of our group cried out in pain, "How could God have let this happen?" My whispered mantra protected me from these thoughts. I knew that God was not a babysitter.

From the first time I learned about the program, I wanted to attend the March of the Living. My Oma's experiences were a part of me. I needed to understand, at least in part, what she went through. I don't know what I expected from the trip, but through Majdanek, Auschwitz and Birkenau I clutched my Oma's book hoping to gain strength by osmosis from her words. Even the religious members of our group cried out in pain, "How could God have let this happen?" My whispered mantra protected me from these thoughts. I knew that God was not a babysitter.

On one of our last days in Poland we visited Treblinka. The Nazis had destroyed the entire camp before the area was liberated. By the time the Allied forces had arrived, a farm surrounded by trees had been built on top of the square of land that had once held the gas chambers. The farm is no longer there and monuments demarcate the location of the train tracks, fence and buildings. Locals enjoy the "park." A family was having a barbeque when we arrived. From a distance, the smoke appeared to float and curl out of the crematorium monument.

Wildlife was everywhere. The sweet sound of birds chirping mingled with the fresh air and woodsy smell that tickled our noses. Butterflies flitted through the trees in search of nectar. "The butterflies are the souls of the children we lost here," my counselor said. I smiled as I thought of the poem I Never Saw Another Butterfly. As we prepared to enter the forest, a butterfly landed on my counselor’s cheek.

I laughed at her startled reaction. "And that one kissed you," I whispered.

I was completely empty. I had lost all faith, not in God – but in man.

I stopped at the kiosk in the parking lot and picked up an Explanation Guidebook. As we entered I read the statistics "874,000 Jews were murdered in Treblinka and there were virtually no survivors." My mind reeled at the staggering numbers. Almost a million Jews and nothing to show for it? We reached the line of boulders that symbolized the fence and I stopped.

Paralyzed by the beauty that masked the horrors seeped into the soil, I fell to the ground. I curled up beside the nearest stone. I was completely empty. I had lost all faith, not in God – but in man.

How could they do this to us? How could this happen in a seemingly civilized world? How do 'innocent bystanders' watch the systematic murder of almost 900,000 people in cold blood and do or say nothing? Where was man when this happened? Where am I when others suffer?

My mind raced through the questions unable to come up with an answer. My Oma had given me one more legacy and I grabbed hold of it now when my mantra failed. I pulled out a pen and a paper and I began to write. I blended in with the scenery as I sat completely still with nothing but my pen moving as it scratched across the paper. My heart bled onto the paper like an open wound. Would I ever overcome these feelings of despair?

My pen paused as my numbed mind began to feel completely spent. I glanced up and away from the paper. I was startled by the delicate form of a butterfly slowly opening and closing its wings on my knee. The words of my counselor came back to me "The butterflies are the souls of the children we lost here." Yes, this child we lost, but there were many more children welcomed into the world every day. Were my sister, my cousins and I not proof that the Nazis had failed?

A new feeling more overwhelming than the last attempted to burst out of my chest. As I watched the gentle movements of the butterfly, I felt only one thing: hope.

Why do bad things happen to good people? I can't answer. Since Moses asked God in the desert, we have been asking why. But the answers remain unfathomable. All I can do is remember that everything happens for a reason whether I understand it or not, and hope that the children of the future will learn from the lessons of the past.

Surviving

Following our week in Poland, we went to Israel. Everyone set their feelings aside for one week to celebrate. We could think about what we went through when we got home. One of my friends could not handle the roller coaster ride of emotions. She had a major breakdown a couple days after our arrival in Israel.

Following our week in Poland, we went to Israel. Everyone set their feelings aside for one week to celebrate. We could think about what we went through when we got home. One of my friends could not handle the roller coaster ride of emotions. She had a major breakdown a couple days after our arrival in Israel.

"How can you expect me to just turn off all these feelings?" she demanded the counselor that had come to try to get her to participate in the activities. "After all we saw and experienced we should just turn around and be frivolous and carefree?"

His response had a profound affect on me although it left my friend unmoved.

"Did the survivors survive so that we could drown in sorrow or so that we could live?"

Surviving meant coming to terms with your experience and building a life.

All my negative thoughts of the inconsistencies between the two legs of the trip vanished. I thought of the pictures of my Oma from after the war when she had returned to Holland to discover she was the only one that remained. She was smiling in all of them.

Was it easy for her to return? I'm sure it was not. Even after the war, there were difficulties to overcome. But being a survivor meant more than having a beating heart when the allies came to liberate you. It meant coming to terms with your experience and building a life.

I no longer count the six million Jews that we lost in the Holocaust; I count my six million Jewish neighbors living in Israel. I no longer dwell on what was in Europe; I live what is today in Israel. My husband and I, both grandchildren of Holocaust survivors, are commemorating the lost lives of the past by building our lives and the lives of the future, our children. I only pray I can instill in them the same faith my Oma instilled in me.