Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

9 min read

Recently published diaries present an unique and damning insider's view of Nazi Germany.

The penultimate year of the war began with a speech exhorting Germans to persevere. Italy was no longer Germany's ally, and the Soviet army was approaching the borders of Poland, Hungary and Romania. The Allied landing in France was imminent. After addressing soldiers and his fellow Germans, Adolf Hitler turned his attention to the Lord himself in his speech to ring in the New Year of 1944. "He is aware of the goal of our struggle," he said. The Lord's "justice will continue to test us until he can pass judgment. Our duty is to ensure that we do not appear to be too weak in his eyes, but that we are given a merciful judgment that spells 'victory' and thus signifies life!"

Two very different men in the German Reich noted their thoughts about Hitler's expression of religious sentiments in their diaries. The first, Victor Klemperer, lived with his wife in a "Jew house" in Dresden, where he wrote about the dictator, using a false name: "New content: Karl becomes religious. (The new approach lies in his approximation of the ecclesiastical style.)."

The second, Friedrich Kellner, lived with his wife in an official apartment in a court building for the Hessian town of Laubach, where he hid his written account of the war in a living-room cabinet. In his commentary on the Hitler speech, Kellner wrote: "The Lord, who has been maligned by all National Socialists as part of their official policy, is now being implored by the Führer in his hour of need. What strange hypocrisy!"

The extensive diary written by Klemperer, a professor of Romance Literature who had been fired from his job in Dresden, was published in 1995 under the title "Ich will Zeugnis ablegen bis zum letzten" ("I Will Bear Witness 1942-1945: A Diary of the Nazi Years"). It is perhaps the most important private document about the Nazis, because it offers an extremely clear-sighted and detailed account of the 12 years of the "Thousand-year Reich" from the perspective of someone who was marginalized. The account details small annoyances and major crimes, daily life and the development of Nazi propaganda.

This document now has a counterpart, the diaries of judicial inspector Friedrich Kellner. The 900-page book begins in September 1938, told from the perspective of a German citizen who was not a Nazi. It also reveals what information Germans could have obtained about the Nazis if they had wanted to.

An Ordinary Family

Kellner, born in 1885, a few years later than Klemperer, was not a privileged man. The son of a baker and a maid, he embarked on a judicial career after graduating from the Oberrealschule, a higher vocational school. At 22, Kellner completed his one year of compulsory military service as an infantryman in the western city of Mainz, and in 1913 he married Paulina Preuß, an office clerk. The couple's only son was born three years later, when Kellner returned from the French front after being wounded in the First World War.

Kellner was horrified, both by the gullibility and barbarism of the people around him.

They were an ordinary, lower middle-class family, but they were also politically active. He distributed flyers, gave speeches and recruited new members for the Social Democratic Party (SPD). Kellner had read Hitler's "Mein Kampf," and he took the book seriously, saying that it brought shame to Gutenberg. After the 1932 elections, in which the Nazi Party became the strongest faction in the parliament, the Reichstag, Kellner requested a transfer from Mainz. In 1933, two weeks before Hitler's appointment as Reich chancellor and the first wave of internal terror, he began working as a government employee in the Laubach District Court. He was an unknown entity in a town with strong Nazi sympathies. It was there that Kellner wrote his diary: a conversation he conducted with himself out of despair that was also an analysis of the present and a planned legacy.

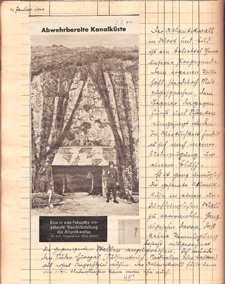

Clippings and observations

Clippings and observations"The purpose of my record," he began, on Sept. 26, 1938, "is to capture a picture of the current mood in my surroundings, so that a future generation is not tempted to construe a 'great event' from it (a 'heroic time' or the like)." In the same passage, on the same day, Kellner revealed a bitter clear-sightedness, when he summed up German postwar history in one sentence: "Those who wish to be acquainted with contemporary society, with the souls of the 'good Germans,' should read what I have written. But I fear that very few decent people will remain after events have taken their course, and that the guilty will have no interest in seeing their disgrace documented in writing."

Ten closely written volumes document the things Kellner experienced, observed and, most of all, what he read and heard. He cut out speeches and calls to action from newspapers and analyzed them, and he made notes about ordinances and decrees. He contrasted the information provided by the government with the facts, both in everyday life in Hesse and at the distant front. He listened to foreign radio stations when he could. But most of all, he analyzed the propaganda from a critical standpoint. Commenting on the 1939 "Treaty of Friendship" with the Soviet Union, he wrote: "We must resort to aligning ourselves with Russia to even have a 'friend.' Russia, of all countries. The National Socialists owe their existence entirely to the fight against Bolshevism (World Enemy No. 1, Anti-Comintern Pact). Where have you disappeared to, you warriors against Asian disgrace?"

Clippings as Evidence

Less than two years later, the warriors had returned, supposedly to preempt an attack by the Soviet Union. On June 22, 1941, Kellner wrote in his diary: "Once again, a country has become a victim of the non-aggression pact with Germany. No matter how our actions are justified, the truth will be found solely in the economy. Natural resources are the trump card. And if you are not compliant, I am prepared to use violence." But hardly anyone saw things the way he did. The women, over tea, liked to refer to the Germans "taking" a city, a region or even an entire country. Kellner was horrified, both by the gullibility and barbarism of the people around him.

Using military news, obituaries of those who died ("for Germany's greatness and freedom"), caricatures, newspaper articles and conversations with ordinary people, Kellner fashioned an image of Nazi Germany that has never existed before in such a vivid, concise and challenging form. Until now, the discussion over German guilt has fluctuated within the broad space between two positions. The one side emphasizes the deliberate disinformation of Nazi propaganda and the notion that ordinary citizens lived in fear and terror, concluding that they couldn't have known better. The other side takes the opposite position, namely that most were aware of what was happening.

In July 1941 he wrote: "The mental hospitals have become murder centers."

Kellner's writings offer a glimpse into what everyone could have known about the war of extermination in the East, the crimes against the Jews and the acts of terror committed by the Nazi Party. He wrote about the executions of "vermin" who made "defeatist" remarks, and about "racial hygiene." In July 1941 he wrote: "The mental hospitals have become murder centers." A family that had brought their son home from an institution later inadvertently received a notice that their child had died and that his ashes would soon be delivered. "The office had forgotten to remove the name from the death list. As a result, the deliberate killing was brought to light," he wrote.

Under Nazi Watch

By reading Kellner's diaries and recognizing what Germans could have known, it's tempting to rethink how the expression "We knew nothing about those things!" came into being. According to Kellner, people simply ignored the information available to them out of both laziness and enthusiasm for German war victories. When this denial of reality no longer worked, when too much had been revealed about what the Nazis were doing in Germany's name, there was no turning back for the majority of Germans. "'I did that,' says my memory," Nietzsche wrote. "'I could not have done that,' says my pride, and remains inexorable. Eventually, the memory yields."

Kellner himself wrote that "this pathetic German nation" had been held hostage by the perpetrators. "Everyone is convinced that we must triumph so that we are not completely lost." The Nazis themselves warned the population against the revenge of the perpetrators. For most Germans, the only conceivable end of the war was victory -- or total annihilation.

Kellner lived until 1970. Despite having been under surveillance by the party and questioned several times, he escaped the concentration camps. In a denunciation written in 1940, a Nazi official named Engst wrote: "If we want to apprehend people like Kellner, we will have to lure them out of their corners and allow them to make themselves guilty. The time is not ripe for an approach like the one that was used with the Jews. This can only happen after the war."

For most Germans, the only conceivable end of the war was victory -- or total annihilation.

In the epilogue, the author's grandson describes how the publication of Kellner's diaries came about. German publishers were not interested at first. But then the diaries attracted attention when, in April 2005, SPIEGEL reported that former US President George Bush had looked at Kellner's original notebooks in the George Bush Presidential Library at Texas A&M University.

Now that they have finally been published, the volumes are likely to find a place next to the Klemperer diaries in German libraries and on private bookshelves too.

Translated from the German by Christopher Sultan.

This article originally appeared in Der Spiegel.

This is a perilous time for the Second World War to be passing from living memory; for the stoic survivors of the Holocaust – those dedicated witnesses of the Nazi blight on civilization – to be reuniting with their loved ones who perished. They depart under the looming specter of what was once considered inconceivable – a third world war and a second Holocaust. Their final cry is for democratic leaders to act immediately and decisively against the existential threat of anti-Semitic totalitarian forces. The Cambridge University Press has now published in English an irrefutable voice from within the Third Reich itself, whose observations demolish the fake histories of revisionists and Holocaust deniers. The title is My Opposition: The Diary of Friedrich Kellner – A German against the Third Reich.