Identifying as a Jew

Identifying as a Jew

4 min read

We cannot write the future. Only our children can do that.

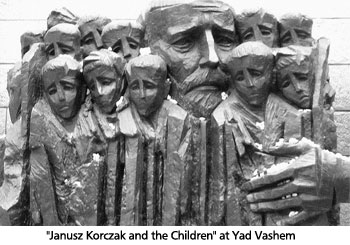

During the nightmare years of the Holocaust, one moment stands out for what it taught about the human spirit. It concerns a man almost unknown in Britain, the Polish-Jewish physician Janos Korczak.

Early on in his medical career, Korczak was drawn to the plight of underprivileged children. He wrote books about their neglect and became a kind of Polish Dickens. In 1911 he founded an orphanage for Jewish children in Warsaw. It became so successful that he was asked to create one for Catholic children as well, which he did.

He had his own radio program which made him famous throughout Poland. He was known as the "old doctor." But he had revolutionary views about the young. He believed in trusting them and giving them responsibility. He got them to produce their own newspaper, the first children's paper in Poland. He turned schools into self-governing communities. He wrote some of the great works of child psychology, including one called The Child's Right to Respect. He believed that in each child there burned a moral flame that if nurtured could defeat the darkness at the core of human nature.

When the time came for the children under his care to leave, he used to say this to them: "I cannot give you love of man, for there is no love without forgiveness, and forgiving is something everyone must learn to do on his own. I can give you one thing only: a longing for a better life, a life of truth and justice. Even though it may not exist now, it may come tomorrow if you long for it enough."

When the time came for the children under his care to leave, he used to say this to them: "I cannot give you love of man, for there is no love without forgiveness, and forgiving is something everyone must learn to do on his own. I can give you one thing only: a longing for a better life, a life of truth and justice. Even though it may not exist now, it may come tomorrow if you long for it enough."

In 1940 he and the orphanage were driven into the Warsaw ghetto. In 1942 the order came to transport them to Treblinka. Korczak was offered the chance to escape, but he refused, and in one of the most poignant moments of those years, he walked with his 200 orphans through the streets of Warsaw to the train that took them to the gates of death, inseparable from them to the end.

More than a million and a half children were killed during the Nazi terror.

More than a million and a half children were killed during the Nazi terror. The first victims were the disabled, the epileptics and the mentally handicapped. Then the killing machine moved on to those the Nazis judged to be subhuman, culminating in the Jews. More than a million Jewish children were lost in those years, a whole murdered generation.

At first children were given lethal injections. Later they were starved or shot or bayoneted or strangled. These methods proved too much for some soldiers and too slow for the projected 'Final Solution.' Thus were born the extermination camps with their gas chambers disguised as showers. A guard at Auschwitz, testifying at the Nuremburg trial, admitted that at the height of the genocide, when the camp was killing ten thousand Jews a day, children were thrown into the furnaces alive. Never has humanity come closer to evil for evil's sake.

Yet there were other stories. There were the almost ten thousand children brought, mainly to Britain, through Kindertransport. Nicholas Winton, then a Stock Exchange clerk in London, organized eight trains from Prague, saving 669 children whose descendants -- numbering 5000 today -- owe their existence to him.

In mainland Europe itself thousands of children were adopted, hidden and rescued in orphanages, convents, monasteries and by men and women driven by ordinary humanity to extraordinary acts of courage, knowing that by saving a Jewish life they were risking their own.

Children -- dependent, vulnerable, defenseless -- are the litmus test of our humanity. Not by accident does the biblical word for compassion, rachamim, come from rechem, meaning a womb. Yet even today, 30,000 die daily from preventable diseases. Hundreds of millions go without adequate food and shelter, education or medical facilities. Will we continue to sacrifice our children for the sake of our hatreds, or will we finally learn to sacrifice our hatreds for the sake of our children? On that question, the fate of humanity may turn.

Korczak was right. We cannot write the future. Only our children can do that. But we can teach them to create a world of respect for difference that may come tomorrow if they long for it enough today.

This article originally appeared in The Scotsman, 27 January 2003