Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

6 min read

Jose Castellanos Contreras rescued 20 times more Jews than Oskar Schindler. Everyone should know his story.

He’s been called the Oskar Schindler of El Salvador, but Jose Castellanos Contreras saved at least 25,000 Jews, twenty times more than Schindler. It’s time for his story to become better known.

Born in 1893 in El Salvador, Jose Castellanos (he is sometimes known by the extra surname Contreras) entered the military, eventually rising to the rank of Colonel, and becoming the Second Chief of the General Staff of the Salvadoran army. In 1938 he was sent abroad, first to work in the El Salvadoran Consulate in Liverpool, England, then to open El Salvador’s new Consulate in Hamburg, Germany.

Col. Castellanos’ grandsons, Alvaro and Boris Castellanos, who have researched their grandfather’s story and made a documentary about him titled The Rescue, speculate that Col. Castellanos’ anti-fascist feelings led him to oppose El Salvador’s autocratic tyrant at the time, Gen. Maximiliano Hernandez Martinez, and that is the reason he was posted abroad. They wanted to get him out of El Salvador. Whatever motive the Salvadoran government had in sending Col. Castellanos to Europe, the move would eventually save the lives of at least 25,000 Jews.

Grandsons Alvaro and Boris Castellanos

Grandsons Alvaro and Boris Castellanos

In Germany, Col. Castellanos was horrified by what he saw. A series of harsh anti-Jewish decrees prevented Jews from working in many professions, going to school, and banned them from public spaces throughout the country. Anti-Semitism was rife. On the night of Nov. 9-10, 1938, mobs roamed the streets of German cities and towns, beating and killing Jews and looting, burning and attacking Jewish homes and businesses. During the Night of Broken Glass (Kristallnacht), as it became known, hundreds of Jews were killed and 30,000 Jews were sent to concentration camps.

Despite the desperate need of Jews to leave Germany, El Salvador, like most countries, refused to issue life-saving visas that would enable Jews to leave Germany. In 1939, Col. Castellanos wrote a letter to the Salvadoran Foreign Minister, describing the dire situation of Jews in Germany and begging him to issue visas to German Jews. Col. Castellanos’ pleas fell on deaf ears and word came that he was forbidden to help.

In 1942, Col. Castellanos was assigned to be El Salvador’s Consul General in Geneva, Switzerland. There he decided to disobey orders and start helping desperate Jews. Col. Castellanos’ first act of resistance was saving his friend, a Hungarian Jewish businessman named Gyorgy Mandl. Mandl changed his name to the more Spanish-sounding George Mandel-Mantello, and became El Salvador’s First Secretary of the Geneva Consulate, a fictitious post and title that Col. Castellanos made up. Col. Castellanos issued Salvadoran nationality papers for Mandel-Mantello and his family, saving them from potential deportation.

Soon, Col. Castellanos and “First Secretary” Mandel-Mantello were issuing Salvadoran passports and visas to other European Jews, identifying them as citizens of El Salvador. While similar visas to other Latin American countries were being bought and sold for huge fortunes on the black market, Col. Castellanos never charged for the life-saving Salvadoran documents he issued.

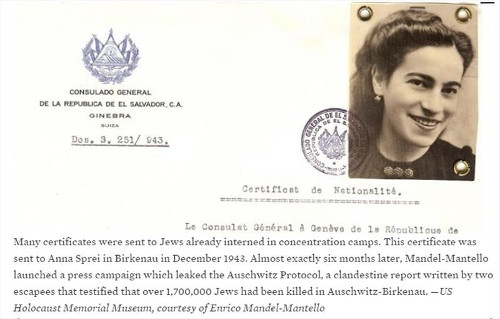

As the war progressed, Col. Castellanos and Mr. Mandel-Mantello realized they couldn’t issue visas fast enough to save the many desperate Jews whose lives were in danger. So they secretly distributed over 13,000 certificates of Salvadoran citizenship, each precious document protecting an entire family. Thousands of European Jews with no connection to El Salvador suddenly became citizens of the small Central American country, offering them protection from deportation and arrest. At first, these certificates were smuggled to Jews living in France; eventually they were sent to Jews in Mr. Mandel-Mantello’s native Hungary as well. In all, Jews from Poland, France, Hungary, Germany and Czechoslovakia found themselves citizens of El Salvador. Col. Castellanos used his diplomatic position to convince skeptical Swiss and other officials that the Salvadoran citizenship papers were in fact genuine.

Salvadoran citizenship allowed European Jews to receive the protection of the International Red Cross, which guaranteed the rights of citizens of neutral countries during the war. In 1944, Col. Castellanos asked Switzerland’s Consulate in Budapest to represent Salvadoran interests as well, and soon the Swiss Consul in Budapest was also working to maintain the rights of these new Salvadoran “citizens” and protect them from the mass arrests that targeted other Hungarian Jews.

In 1944, after two years of working secretly issuing thousands of visas, passports and certificates of citizenship, Col. Castellanos finally received permission from El Salvador to continue his life-saving work openly. He and Mr. Mandel-Mantello increased the number of papers they printed, eventually gaining an ally in Budapest: Carl Lutz, the Vice Consul at the Swiss Legation in Hungary’s capital.

With Lutz’s help, El Salvador issued thousands of official-looking, notarized documents guaranteeing citizenship and protection to Jews in Hungary, Poland, and other European countries, where they otherwise would have perished. As word of the Salvadoran visas being issued in Hungary grew, Carl Lutz moved his production facilities to an abandoned glass factory, where he had more space to churn out Salvadoran citizenship papers. In all, it’s estimated that somewhere between 30,000 and 50,000 Jews were saved by what some call the “El Salvador Action” of World War II.

After the War, Col. Castellanos lived a quiet life, rarely talking about his wartime heroism. The writer Leon Uris tracked down a then-retired Jose Castellanos in 1972, and in 1976 he gave his only interview about his wartime activities in a brief radio interview. After being posted to London after World War II, Jose Castellanos returned home and retired; he died in San Salvador in 1977.

Frieda Garcia, Castellanos’ daughter, recalls that her father played down his heroism and rarely talked about the thousands of lives he saved: “Whenever I asked him, he would say that he didn’t do anything another person in his place wouldn’t have done,” she recalled.

Jose Castellanos’ daughter, Frieda, at Yad Vashem

Jose Castellanos’ daughter, Frieda, at Yad Vashem

In 1999, the Jerusalem City council honored Col. Castellanos, naming a thoroughfare in the Givat Masua neighborhood El Salvador Street, and thanking Col. Castellanos’ granddaughter who attended the ceremony for her grandfather’s heroism. In 2010, Col. Jose Arturo Castellanos Contreras was honored as “Righteous Among the Nations” by Yad Vashem in Israel and a tree was planted in his honor.

In 2012, when Col. Castellanos was honored by the Anti Defamation League, his daughter Frieda Castellanos de Garcia noted that it’s more important than ever now to remember her grandfather’s legacy. “These stories have to be told,” she warned. “Some leaders of the world are denying the history of the Holocaust. The only way that we can avoid another horror of the Holocaust is by letting people know that it really existed.”