Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

7 min read

Giving voice to my uncle’s sacred memories of the Holocaust.

I made a promise.

I gave my word to my dear Uncle Yanky, Rabbi Jacob Jungreis, that I would not allow his story to be forgotten.

So I am sitting at the table of my beloved mother’s brother with notebook and pen in hand. We sit for hours.

I am the man who has seen affliction…My soul remembers well (Lamentations, 3:1).

When I leave his home I am holding my own Book of Lamentations. Each page cries out to be shared and remembered. We dare not forget. I will do my best to bring justice to the sacred memories he entrusted to me. They haunt my soul.

As a five-year-old child in Szeged, Hungary, in 1938, walking to school I would be yelled at, “Bidosh Zsido! Dirty Jew! You killed God!’

Every day the taunts and screams were thrown at me and I never understood what that meant. I was always a frightened little boy. But this was my life. We did not know anything different or how terrible things would become.

One day in 1943, I am standing next to my father, your Zayda who was the Chief Rabbi of Szeged, in the room filled with his holy books. A man comes in. Mama, your grandmother, invites him to eat with us. We always had a house filled with people.

My uncle, Rabbi Jacob Jungreis, holding his baby sister, my mother Rebbetzin Esther Jungreis A'H

My uncle, Rabbi Jacob Jungreis, holding his baby sister, my mother Rebbetzin Esther Jungreis A'H

I will never forget the moment. His eyes are hollow, dark. He says he escaped a concentration camp.

“Rabbi! You know they are making soap out of our people?”

Zayda’s hat falls off. His head slumps down. Mama cries out. “That cannot be!”

No one believed it. It could not happen here. Hungary was a cultured country. Szeged was a civilized city. We had colleges, universities, plumbing, and electricity. There was art and music, museums and concerts.

We didn’t comprehend the truth. The carnage was being covered up. There were wild rumors flying. We could not fathom that such atrocities existed. We couldn’t believe it could happen in our Hungary. Those who dared talk about death camps were shouted down or called alarmists. There were no news stories or radio shows revealing the murder of the Jews. Many who had been taken away were forced to send postcards back saying that they are fine; they are being taught a trade because Jews are lazy and they will soon be home. Arbecht macht frie – “work will set you free” was the sign greeting those who entered the extermination camps.

Later when we wanted to leave Hungary there was no getting out. Even if we could, no country in the world wanted us. There was no spot on earth for a Jew to find shelter.

Rabbi Jacob Jungreis

Rabbi Jacob Jungreis

Soon after people started arriving all hours of the night. They were running across the border smuggling themselves into Szeged.

At 2 AM we would hear a frantic knock.

“Vers duz? Who is it?”

“A Yid.”

A Yid? We must open the door. I never knew where I would be sleeping. Mama spread sheets in the corner of every room. Fifty people crammed into our home looking for a place to breathe.

In time Szeged would become a stifling ghetto.

Young men drag the millstone and youths stumble under the wood. Gone is the joy from our hearts, our dancing has turned into mourning (Lamentations, 5:13).

Young Jewish boys were forced to join work brigades and slave labor camps. They were brought to our city because we were near the Tisza River, a hub for travel. Once a month a boat would take 300 of our finest boys to Bor, where they were forced into backbreaking labor. There, many were cruelly shot, sent on death marches and slaughtered.

Zayda and Mama were anguished. These beautiful Jewish young men were here in our city. They were being sent to their death. We cannot turn our backs on our brothers but how can we possibly help them?

Zayda and Mama spoke to the Jewish doctors of the city. “How can we get these boys to miss the boat and escape their death sentence? How can we help them be sick enough but then get well?”

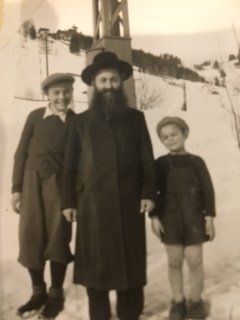

Zayda with his two sons, Jacob and Benjamin in the DP camp in Switzerland after the Holocaust.

Zayda with his two sons, Jacob and Benjamin in the DP camp in Switzerland after the Holocaust.

In Mama’s kitchen concoctions were made. One with unpasteurized milk, another with soybeans crushed into powder. If injected, one would get high fever for 48 hours and miss the boat. If the paste was put onto the eyelids, it mimicked trachoma. But how to get these vials to the boys?

Zayda would take with him my little sister, your beloved mother, Rebbetzin Esther Jungreis of blessed memory, to visit these young men while they were being held. Since he was the Chief Rabbi, Zayda was given some precious time with the prisoners. He blessed each one with his tears, lovingly embraced them and prayed with them. Mama sewed the poisonous vials into my sister’s coat lining. While no one was looking, the vials were given over and countless lives were saved.*

There was never a doubt that we had to do whatever we could to save lives. From the earliest age we were given this understanding. Feel the pain of your brothers and sisters. Never look away at the suffering of your people.

My eyes shed streams of water at the shattering of our people” (Lamentations 3:48).

June 1944, midnight. A knock at the door. “Pack up! You will need to leave your house!”

Mama woke us up and bathed us one last time. We spent three days at the railroad station. Zayda took only the handwritten Torah notes of his illustrious ancestor Rabbi Modche Benet and the holy tefillin given to him by his Zayda. Throughout our days in the concentration camps these were never lost and imbued us with continuous faith.

Zayda and Mama in America begin again

Zayda and Mama in America begin again

We were kept in pop up tents. There was a torrential downpour. We were freezing, hungry and frightened. In middle of the night my sister, your precious mother, developed a high fever. Zayda went to search for an aspirin. Three hours later he returned; there was no aspirin. Zayda and Mama held your mother in their arms, rocking her while they were crying. I was sitting across from them, silent. I couldn’t bear to watch my parents suffering. But when I looked away I felt guilty.

I was 11 years old.

They pushed us into cattle cars. There were barking German Shepherds and rifles. 90 people jammed on top of each other. We were suffocating. All around people screaming, “I have no air! I have no air!” We didn’t know it at the time but we were being taken into the Valley of Death, Bergen Belsen.

There is so much more that needs to be written. Our space here is limited.

Over these things I weep; my eyes run with water because a comforter to revive my spirit is far from me (Lamentations, 1:16).

I pray that I have given life to the memories that have lied dormant within my uncle’s soul. I hope to share more so that we can revive the light of those whom the world believed they had extinguished.

This Tisha B’Av, take a moment and mourn for your people. For a world that was. Dare not remain silent when you witness the suffering of your nation.

*Years later, while speaking across the world, my mother met some of these very boys, now grown men, who had survived through these dangerous encounters. The reunion was incredibly emotional.