Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

16 min read

She buried her Jewish identity. Her son embarked on an astonishing quest to reclaim it.

Tom Gale never knew what hit him. En route to a weekend home from college, he was cruising along a Canadian highway at 95 mph in his bright red Triumph Spitfire. The nasal decongestant he’d taken that morning made him drowsy.

“I took my eyes off the road for a minute,” Tom recalled, “and that’s all it takes at 95 mph.”

The convertible, with its top down, rolled over him.

Tom awoke two weeks later. “Most of the bones in my body were broken, including all my ribs. The doctors kept me unconscious during those first, most painful weeks. It was more humane.”

Tom’s odds against living were set at 1,000 to one. But since he was young and in top physical shape, his body was able to fight back. “During those two weeks I lost 80 pounds. When I woke up, I didn’t even recognize myself.”

Tom had a massive spinal injury which left the lower half of his body paralyzed.

Born of strong stock, Tom came to relish the challenge. “I resolved to move my toe. As the furthest extremity from my brain, it was my most effective way to demonstrate voluntary muscle control.”

One day he felt his toe twitch. He was able to move it! Surgeons flew in from around the country to witness this groundbreaking achievement.

After 18 months of intense physical therapy, Tom managed to struggle back to his feet and walk with a cane.

“The doctors put the odds against that at 5,000 to one.”

The accident shook Tom to the core. “Facing mortality always gets you thinking,” he says.

He began to explore spirituality.

Tom grew up in a Christian home, the eldest of four children. “My mother strongly believed in God, and always said she was Christian. But she had no religious observance and never stepped inside a Church. I never knew why.”

There were other unexplained things as well: His mother’s staunch support of Israel. The aunt who had a Jewish home. And the grandmother who kept a box of matzah hidden under her bed.

A voracious reader, Tom explored the gamut of religions, from the traditional to the bizarre. He didn’t find what he was looking for.

But at one lecture he met the woman who would soon become his wife.

Katherine had grown up on a farm in rural Ontario, with a similar religious upbringing as Tom. The foundation of her home was a strong belief in God, without Christian overtones or imagery.

Gershom’s mother never uttered a word about the secret buried deep inside.

One day in 1983 Tom wandered into a Jewish bookstore in Toronto. “I told the man I wanted to study Talmud,” he recalls. “He looked at me rather strangely, then handed me an English translation of Tractate Brachot.”

Tom devoured the material. “I can’t explain it,” he says, “but it was pulling me like a magnet.”

One time Tom was reading the Talmud and weeping. His mother asked, “What’s the matter?”

“It’s just so beautiful,” he said. “This is speaking to me. I feel like I’m experiencing a ‘call home.’”

Tom’s mother didn’t say a word. But as he would eventually discover, it required superhuman effort to hold herself back.

In the meantime, Tom’s wife was looking on with curiosity. One day he brought home a copy of Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan’s “Living Torah.” Katherine read it and said, “I’ve been looking for truth my entire life. The answer is here. Now what do we do?”

Tom opened the phone book and called a rabbi who happened to be Orthodox. They began studying for conversion.

It took nearly five years, but when the conversion was finalized, Tom and Katherine – now Gershom and Dinah – fulfilled their dream and, along with their two young sons, moved to Israel.

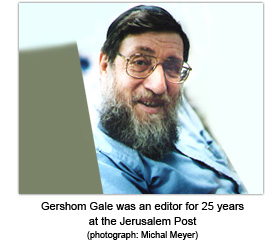

Gershom was hired as an editor for the Jerusalem Post, where he would work for the next 25 years.

Amidst all this – search, discovery, conversion, aliyah – Gershom’s mother never uttered a word about the secret buried deep inside.

Gershom’s mother grew up as Miriam Zimmerman in a Jewish family in the Polish city of Lodz. They celebrated Shabbat and the Jewish holidays. In 1939, when the Nazis invaded Poland, Miriam’s father thought it would be safer in the larger city of Warsaw.

The move proved inauspicious. In time, the Nazi beasts clamped down on Warsaw’s 400,000 Jews, herding them into a 1.3 square-mile cage called the Warsaw Ghetto.

At the tender age of 13, Miriam became surrounded by starvation, disease, and deadly beatings at the hands of uniformed monsters.

The Zimmerman family lived in a cramped room. Miriam, whose blonde hair and blue eyes gave her a “gentile look,” was sent daily to forage for food.

By the spring of 1943, Miriam’s father decided that their prospect of survival was slim in the Ghetto, and they must go into hiding on Warsaw’s “Aryan” side.

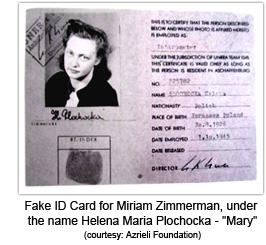

Through the kindness of a Christian woman named Christine Panek, Miriam’s family was able to obtain false Christian papers.

Miriam Zimmerman henceforth became known as Helena Maria ("Mary") Plochocka, the “cousin” of Christine Panek. Miriam’s mother became her “aunt” Jadwiga Mozdrzvaske. And Miriam’s sister, Chaya, became a “cousin” named Helen.

These new identities became the family's unshakeable guard against getting caught. Throughout the war, they used their Christian names exclusively, and never once spoke of their true relationship as parent, child, sibling.

Even out of the Ghetto, the fear of death was never far. Carrying false papers was not sufficient insurance, as Miriam’s uncle discovered. He was stopped on the street by a group of Gestapo soldiers who demanded that he expose himself. When they saw he was circumcised, they shot him dead.

The Zimmerman family lived in an apartment with Christine, where they often hid in a cupboard so tiny that they were truly in danger of suffocating. "We were constantly petrified that our secret would be discovered and that we would all be killed," Miriam later recalled.

One time the apartment was broken into by a bunch of Nazis. A stormtrooper shoved Miriam into the bathroom, put a gun to her head and said: “If you do anything, I will shoot you right here.” Miriam looked up at him very calmly and said: “If you shoot me, I will haunt you for the rest of your life.”

He left her unharmed.

One day in 1944, pandemonium broke loose when a German officer was killed in the Wola district of Warsaw where Miriam’s family lived. The German response was a rampage of shooting, looting and raping of Poles. Forty Polish men were taken out of their homes and shot dead.

Miriam heard shots in the street. She ran outside. There she found her father... lying in a pile... of dead bodies.

A few weeks later, Miriam awoke at 2 a.m. to find someone sitting on her bed. It was her dead father: “I came to warn you. This house will be bombed in the next 10 minutes. You must get to shelter immediately.” Miriam believed it strongly enough to wake up her mother and sister and convince them to follow her. As soon as they exited, the building blew up.

Although they had Christian papers, Miriam, along with her mother and sister, were rounded up as “Polish political prisoners” and deported in a cattle car. “The heat was oppressive and we had no water to drink,” Miriam says. “Little droplets of water appeared on the walls of the train car, created by the breath of all the trapped people, and we tried to lick the droplets off the walls because we were so thirsty.”

The train took them to Ravensbrück, the notorious women's concentration camp filled with gypsies, nuns, Polish patriots, criminals, Soviet POWs, Communists, lesbians – and about 15% Jews.

As a “Christian,” Miriam was given a “red triangle” patch designated for political prisoners.

Soon after Miriam was transferred to Buchenwald. Conditions in that camp were unspeakable, with widespread starvation, disease, human experimentation, backbreaking labor, and execution. One time an SS officer kicked Miriam in the side of the face – knocking out half her teeth and breaking her jaw. “I could never open my mouth properly after this happened,” she says.

Miriam, at age 17, weighed 80 pounds.

Due to malnutrition, her legs became covered with oozing boils. "The sores were so deep that I could put my finger into them and touch the bone in my leg," she says.

She was forced to stand for hours in the cold, with bare feet and hands. To this day, her swollen hands are a grim reminder of freezing in Buchenwald.

In the spring of 1945, with the Soviet Red Army rapidly approaching, the Nazi machine decided to exterminate as many prisoners as possible, in order to “silence the accusing witnesses.” As the Russians neared closer and closer, the SS forced 20,000 prisoners on a death march.

For three weeks, Miriam, her mother and sister slogged through the freezing German countryside. Anyone who couldn’t keep up was shot on the spot. Eighty-five percent did not survive the march.

“We found dirty water to drink... and occasionally found some animal food,” Miriam recalls.

One day, their group was guarded by a single teenage soldier. When he fell asleep, the women sought to tear him to bits. But Miriam considered another idea: She threw his rifle into the river. When the soldier heard it hitting the water, he woke up to see 300 angry women staring down at him. He quickly ran away.

The women wandered into the town of Plzen, Czechoslovakia. The war was finally over. “A man came out of church with a little boy in his arms and stared at us,” Miriam recalls. “I saw his eyes go to my oozing legs with disgust.” The man handed Miriam his shoes and then went to bring them food.

Miriam, her mother and sister, who all miraculously survived, were sent to a displaced persons camp in Aschaffenburg, Germany. A Canadian Army officer named Arthur Gale had been appointed by the United Nations as director of the camp. Arthur didn't know any Polish and needed someone to interpret. The promise of extra food made Miriam Zimmerman immediately volunteer, despite knowing no more than 20 words of English.

As Miriam and Arthur spent more time together, they became good friends and decided to get married. "I told Arthur that I was Jewish," she says, "and he said he did not care at all."

(Miriam's sister Helen met a Jewish-American soldier and had a Jewish wedding in the DP camp. They were happily married for 68 years and lived a Jewish life in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Helen’s husband died in 2013.)

Meanwhile, newlyweds Miriam and Arthur Gale moved to Nova Scotia, Canada, where they raised a family of two boys and two girls.

Miriam tried to use her war lessons to help others. “I raised my kids to be tolerant and we welcomed immigrant families into our home,” she recalls. When neighbors from Jamaica encountered discrimination, Miriam “adopted” them. When refugees from China and Sri Lanka showed up in Toronto, Miriam moved them into her house and helped them get settled. “I did these things because of what Christine Panek did for us in order to save our lives in Poland.”

Miriam kept her mother and sister under a strict oath of secrecy.

And yet, Miriam was so traumatized from the war that decade after decade she insisted that her mother and sister perpetuate the charade of "a Christian family, whose father was a fallen Polish general, and whose mother had died of cancer." Under an oath of absolute secrecy, Miriam's mother and sister acted as “the auntie and cousin who adopted her” – forbidden from ever revealing anything about their real family background.

Miriam says: “I learned that to be Jewish meant tragedy … I simply thought about what I needed to do to keep myself and my family alive."

Imagine the irony of their oldest child, Tom, experiencing a near-fatal car crash and then "converting" to Judaism.

Only later would he find out what a massive internal struggle his mother's silence was.

Miriam remained in contact with Christine Panek, the righteous gentile who'd saved her life during the war without ever accepting money. Over the years, Miriam would send gift packages, and even went to Poland to visit Christine.

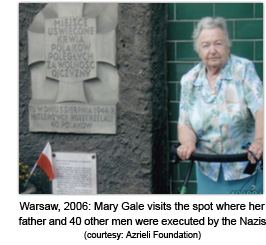

In 2006, to celebrate her 80th birthday, Miriam took a second trip to Poland, accompanied by her daughter. While visiting the spot where her father was murdered, Miriam could no longer control herself.

In 2006, to celebrate her 80th birthday, Miriam took a second trip to Poland, accompanied by her daughter. While visiting the spot where her father was murdered, Miriam could no longer control herself.

“I could see the bodies again and smell the burning rubber,” she says. “The trauma of my father’s death was right in front of my eyes.”

By this time, Miriam had two heart attacks, and the doctors told her she would not survive a third. The secret of her Jewish identity had been weighing heavily all these years, and she didn’t want to take that fact to the grave.

Plus, Miriam no longer had the strength to hold it all in.

Her iron will broke.

Twenty-five years after her son Tom converted and became Gershom, she told her stunned daughter: “We are not who you think we are. We are Jews.”

Miriam made her daughter swear not to tell anyone, even Gershom. And although the secret remained largely under wraps, slowly the walls came down. In 2010, Miriam’s other daughter, Christine (named after Christine Panek), became engaged to a Jewish man. Miriam again revealed the secret, telling her daughter: "You might as well have a Jewish wedding!"

Yet Gershom still didn’t know the truth. One day, his younger son Joshua was in Canada and asked his grandmother point-blank: “If you are Jewish, I have a right to know.” She broke down and revealed it. That’s how Gershom found out.

“I always suspected that Mum was Jewish,” Gershom told Aish.com from his home on the outskirts of Jerusalem. “Over the years I asked her several times if she was Jewish, and she always answered, ‘No, I’m Christian.’ She was very firm about it, and since she's my mother, I had no reason to doubt her word.”

Still, there were various signs over the years. Dinah recalls one incident: “The phone rang at home and when Miriam answered, the caller shouted ‘Jew!’” She was afraid she’d been discovered and that they were coming to get her. She turned white as a sheet.”

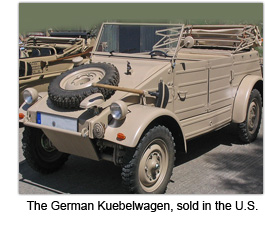

Gershom recalls an occasion when his grandmother had a panic attack. The Volkswagen Kübelwagen was used as a Nazi staff car during World War II. In the early 1970s it was sold commercially in North America as "The Thing." “My grandmother saw such a car driving down the road in Canada and she freaked out. She thought she was back in Poland.”

There were other signs as well. Dinah describes how before she was married, Gershom’s grandmother “leaned across the table, looked me straight in the eye and said, ‘Katherine is a Jewish name.’ I didn’t know what she meant at the time. In retrospect it was her way of saying: ‘Judaism is important and I want you to go in that direction.’”

Was Gershom upset with his mother for keeping the secret all those years?

“At first I was very angry. I had gone through a lengthy and unnecessary conversion process, and she stood silently while it was all happening. In exasperation, I told her: ‘You’ve been lying to me all my life!’ I eventually came to understand that she did it for my own protection. She endured a lifelong trauma and didn’t want me to ever repeat it.”

What about Arthur Gale? Gershom says: “My father once told me that Mum had a secret that only he knew. But he wouldn’t share with me what it was.”

What about Miriam’s sister, Helen, sworn to secrecy all those years? Gershom says: “She has apologized profusely for not saying anything all along, but my mother had her under strict oath not to tell.”

While Miriam has visited Gershom in Israel twice, she remains traumatized by the memories of having seen people shot, poisoned, hanged, and thrown out of windows. She has persistent “nightmares and deep fears,” terrified that should she admit, “I am a Jew," the hatred and horrors will revolve again.

For 60 years she kept her Buchenwald prisoner coat hidden in a box, along with her prisoner patch – number 29943.

But the secret is no more.

Miriam now eagerly shares her story in recent TV and newspaper interviews, and a brand new Holocaust memoir for Canada's Azrieli Foundation, entitled "Identity Lost and Found."

Why did Miriam decide to tell her story now?

“The people in my past died because they were Jews, and I am still afraid to admit who I am.”

“I want to make amends with the people in my past, and I feel guilty for not carrying on the traditions of the Jewish people,” she says. “They all died because they were Jews and I am still afraid to admit who I am.”

Another reason is more personal: Miriam seeks to purge her demons.

“I feel like I am on a seesaw and sometimes I think that it is too late to change my life story,” she says. “My secrets are hanging me and they are very hard to undo. I feel like they are choking me to death.”

"I hope that telling my story will help with my flashbacks and that the truth will untangle me somehow. I am like a pot bubbling with lies and need to tell the truth rather than continue stirring the lies. But the prospect of telling the truth still terrifies me."

And what about her Jewish son who “converted” and made aliyah?

"I am pleased that some members of my family are carrying on the Jewish traditions that I learned as a child,” she says. “It is like a miracle to me that of all the religions, Gershom picked Judaism. Maybe it was his destiny."

Mary Gale quotes courtesy of the Azrieli Foundation and Ruth Krongold

that Miriam should have had to carry the burden of guilt or her children's fury in addition to all the anguish she had already suffered is an obscene consequence of The Final Solution. fate imprinted her with a faith beyond denomination & a grief beyond measure. may she be blessed & relieved of such dismal scrupulosities, and may no one - least of all herself - judge her, lest she haunt you for the rest of your lives.,

What a remarkable story.

My heart aches for Miriam. I sincerely hope she finds inner peace before she meets her maker.I do not judge her or fault her in the least!

Hashem gave her “Yiddishe Naches”!

That is the way He stayed by her side!

It reminds me of the brilliant book Family history of fear by Agata Tuszynska.

Amazing

As ALWAYS, Aish's holocaust testimonies are most compelling. Ever consider publishing them as a book?

Fascinating and moving story about unimaginable suffering and transcendence.