Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

5 min read

Newly discovered documents reveal that a reviled Bolivian tycoon was one of the greatest heroes of the Holocaust who rescued over 9,000 Jews.

Newly discovered documents have shown that a long-reviled Bolivian tycoon of the 1940s was in fact one of the greatest heroes of the Holocaust, rescuing over 9,000 Jews and finding jobs and support for them.

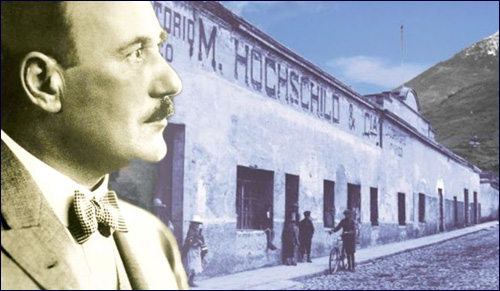

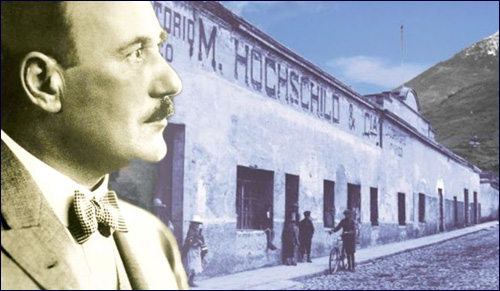

Mauricio Hochschild was one of three “Tin Barons” who controlled tin mining in Bolivia in the 1940s. Together, the Tin Barons controlled most of the world’s tin production. They had abysmal reputations.

Far from being a callous tycoon, Hochschild worked feverishly to save thousands of his fellow Jews from the Holocaust.

Hochschild, a Jew, was considered to be short-tempered and ruthless. Born in Germany, Hochschild had moved to Bolivia at the age of 40 and built up a business, only to be driven out of his adopted country in 1944, when he was briefly jailed for not paying a new tax. When he died in 1965, in Paris, his reputation in Bolivia was for being greedy and unprincipled.

All that has changed in recent months, when workers for the Mining Corporation of Bolivia found a trove of old documents. Filthy, ragged, and mixed in with garbage, the pages were in terrible condition. Workers started going through the papers and eventually realized they belonged to Mauricio Hochschild whose business had been nationalized in 1952. The documents contained a huge surprise: far from being a callous tycoon, Mauricio Hochschild worked feverishly for years to save thousands upon thousands of his fellow Jews from the Holocaust, helping them obtain visas, then providing jobs, housing, schools and other aid for them once they reached safety in Bolivia.

All that has changed in recent months, when workers for the Mining Corporation of Bolivia found a trove of old documents. Filthy, ragged, and mixed in with garbage, the pages were in terrible condition. Workers started going through the papers and eventually realized they belonged to Mauricio Hochschild whose business had been nationalized in 1952. The documents contained a huge surprise: far from being a callous tycoon, Mauricio Hochschild worked feverishly for years to save thousands upon thousands of his fellow Jews from the Holocaust, helping them obtain visas, then providing jobs, housing, schools and other aid for them once they reached safety in Bolivia.

Bolivian media has taken to calling Mauricio Hochschild the “Bolivian Oskar Schindler”. The comparison is inexact: while Oskar Schindler saved over a thousand Jews by employing them as slave laborers in his factories, Hochschild saved over 9,000.

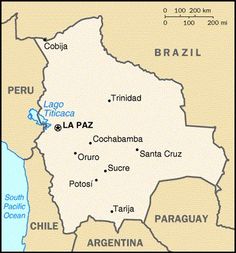

Hochschild’s plan started in the 1930s, as he watched the rise of fascism in his native Europe. Hochschild was close to Bolivia’s volatile and short-lived President German Busch, who tried to stimulate Bolivia’s economy by admitting immigrants from Europe. Hochschild helped shape this plan, allowing Bolivia’s consulates in Zurich, Paris, London, Berlin and Vienna to issue visas to would-be immigrants, many of them Jews.

Refugees started pouring into Bolivia. From late 1938 until mid-1939 alone, 12,000 Jews fled Europe to the Latin American state. Some of these desperate refugees sailed on comfortable passenger ships; many more packed into unhygienic, barely seaworthy ships. The ships docked in the port of Arica, in nearby Chile, and then they were taken by train to Bolivia’s capital La Paz. The route became known as the Express Judio, or the “Jewish Express”.

Once in La Paz, there was woefully little infrastructure to help Jewish arrivals. Many were housed in jails until something more permanent could be found. Few of the refugees spoke Spanish and most arrived in Bolivia penniless.

Once in La Paz, there was woefully little infrastructure to help Jewish arrivals. Many were housed in jails until something more permanent could be found. Few of the refugees spoke Spanish and most arrived in Bolivia penniless.

The American Joint Distribution Committee helped settle some of the refugees, but Mauricio Hochschild wanted the refugees to be able to work and support themselves. It seems he also viewed the Jewish refugees as a key opportunity to help strengthen Bolivia’s economy and society. Hochschild helped found two new organizations to help his fellow Jews.

SOPRO, the Sociedad de Proteccion de los Inmigrantes Israelitas, or the Society for the Protection of Jewish Immigrants, provided monetary assistance to help the new refugees get on their feet; Hochschild personally contributed the thousands of dollars each month it took to keep SOPRO running.

He also bought three agricultural estates in the Bolivian province of Nor Yungas where Jewish refugees could work, and founded an organization called SOCOBO, the Sociedad Colonizadora de Bolivia, sometimes translated as the Society for the Protection of Israeli Immigrants, to manage the agricultural projects there. In addition, Hochschild employed Jewish refugees in his mining business.

Hochschild seems to have been known as a philanthropist who could help Jews the world over. One letter in the cache is from French authorities asking Hochschild to receive and settle a thousand Jewish orphans. Another letter, from a Jewish kindergarten in La Paz, Bolivia, asks for Hochschild’s help in expanding the school “in view of the number of children who are here and others who want to come.”

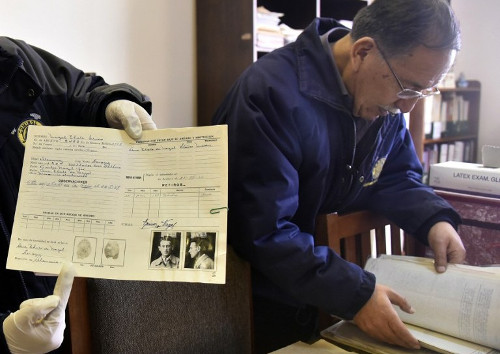

Edgar Ramirez (right), the head of the archives in the Bolivian state mining company COMIBOL, with unearthed documents in El Alto, Bolivia. (Aizar Raldes/AFP)

Edgar Ramirez (right), the head of the archives in the Bolivian state mining company COMIBOL, with unearthed documents in El Alto, Bolivia. (Aizar Raldes/AFP)

Historians reviewing the papers now believe that Hochschild was instrumental in helping political resistance to Nazi Germany. “I am convinced that Hochschild was part of the anti-fascist apparatus,” explains Edgar Ramirez, the archive director of the Mining Corporation of Bolivia. “In order to do what he did he had to be a man linked to the resistance movements that were operating around the world.”

In Bolivian popular imagination “Hochschild was the bad guy,” Ramirez explains. Now they are realizing he was a national hero.

The documents are causing many Bolivians to question what they know of their history. In Bolivian popular imagination “Hochschild was the bad guy,” Ramirez explains. Now they are realizing he was a national hero. “He saved many souls from the Holocaust by bringing them to Bolivia and creating jobs for them,” explains Carola Campos, head of the Bolivian Mining Corporation’s Information Unit.

In the 1940s, 15,000 Jews lived in Bolivia; almost all of them had come as refugees from Nazi Europe. For years, the community flourished, with synagogues, schools, burial societies, aid organizations, sports leagues, a retirement home, and Zionist clubs. Many Jews have emigrated from Bolivia, joining larger Jewish communities in Israel, Argentina, and the United States. Today, Bolivia’s Jewish community numbers under 500 people.

Thousands of Jews around the world continue to have a key link to Bolivia, having found safe haven in this country. Today, thanks to the a cache of dusty old papers in a company warehouse, Mauricio Hochschild, the man who rescued thousands of more Jews than Oskar Schindler, is at long last being acknowledged and his story rewritten.