Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

4 min read

The story behind the Queen of Soul’s hit song, Respect.

Like others around the world, I’ve been listening to Aretha Franklin’s anthem “RESPECT” since the singer’s death on August 16, 2018 at the age of 76. With its catchy lyrics demanding human dignity, Franklin’s song became an anthem when she recorded it in 1967. Listening to it has become a way to remember Aretha Franklin, the Queen of Soul.

That RESPECT would become such a cultural touchstone wasn’t always a given. At the time she recorded it, Aretha Franklin was a deeply troubled singer trapped in an abusive marriage, and the song, originally written by Otis Redding two years earlier, was a man’s song that had failed to capture the public’s imagination.

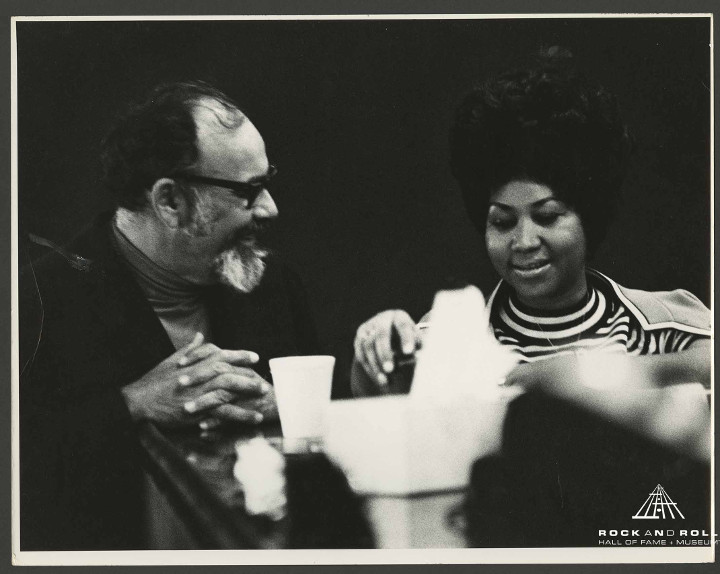

The producer who transformed it into a hit - and Ms. Franklin into a star - was Jewish industry executive Jerry Wexler. It was Mr. Wexler, as well as several other Jewish musical writers and producers, who helped Aretha Franklin flourish artistically and find her voice.

Jerry Wexler and Aretha Frankin

Jerry Wexler and Aretha Frankin

Born in 1917 to Jewish immigrants in New York, Jerry Wexler began his career as a reporter, and distinguished himself by his deep compassion and decency. At a time when recordings made by artists in the Black musical tradition were commonly called “race records”, Mr. Wexler resisted the term. In 1947, while working for Billboard Magazine, he started calling the gospel-infused music “rhythm and blues”, and the term stuck, helping Black music achieve the dignity it deserved.

For Wexler, giving Black American musical genres their due was personal. “As a Jew, I didn’t think I identified with the underclass,” he explained years later. “I was the underclass.” He also understood the universal power of music to inspire and transform.

Jerry Wexler eventually moved into record production, working at the Atlantic record label. In a career spanning 50 years, he signed and produced artists including Ray Charles, Joe Turner, Solomon Burke, Wilson Pickett, Dusty Springfield, Bob Dylan and Willie Nelson. Rhythm and blues became his specialty, and he helped shape the genre and bring it to prominence.

One of his greatest hits was Aretha Franklin’s RESPECT. To record it, Wexler brought Ms. Franklin and the rest of his team to Alabama, a region steeped in rhythm and blues. Aretha arrived with her husband and manager, Ted White, and he was openly abusive to her during the trip. (The couple divorced two years later.) Though Ms. Franklin only spent one day in Alabama recording that first album with her new label, it was enough to transform the way she sang.

Instead of singing in different contemporary styles, as she had been doing to middling reviews for the previous several years, Ms. Franklin went back to the gospel-infused music of her youth. “We were simply trying to compose real music from my heart,” she later explained. Jerry Wexler suggested she sing RESPECT, and took the rare step of letting her improvise and collaborate during the recording session. “He provided the vehicle to allow me to perform and express myself,” Aretha Franklin recalled after Wexler’s death in 2008.

In his autobiography, Mr. Wexler wrote about his decision to encourage Ms. Franklin to go back to her R&B roots: “My idea was to make good tracks, use the best players, put Aretha back on piano and let the lady wail.”

RESPECT quickly climbed to Number One in the charts, and earned Ms. Franklin the first of her many awards: a Grammy for best R&B recording and for best female solo R&B performance. She went on to record three more albums with Jerry Wexler, including seven more top10 hits.

It was Wexler who put Aretha Franklin in touch with Jewish songwriters, some of whom wrote songs that became iconic standards such as “I Say a Little Prayer” by Burt Bacharach, “Natural Woman” by Carole King and Gerry Goffin, and “Spanish Harlem” by Jewish songwriting trio Jerry Leiber, Mike Stoller and Phil Spector.

These and other songs spoke urgently to a new generation that was trying to claim that women and minorities and other overlooked groups had worth and deserved respect. “The call for respect went from a request to a demand,” Wexler later wrote. “And then, given the civil rights and feminist fervor that was building in the 1960s, respect - especially as Aretha articulated it with such force - took on a new meaning. ‘Respect’ started off as a soul song and wound up a kind of national anthem.”

Aretha Franklin recognized the universal nature of the need for respect and dignity. Speaking to Jet Magazine in November 1970, Aretha insisted that everyone had a place in her music. “It’s not cool to be Jewish, or Negro, or Italian. It’s just cool to be alive, to be around,” explained the Queen of Soul.