Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

5 min read

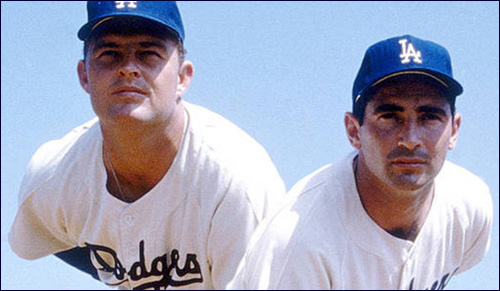

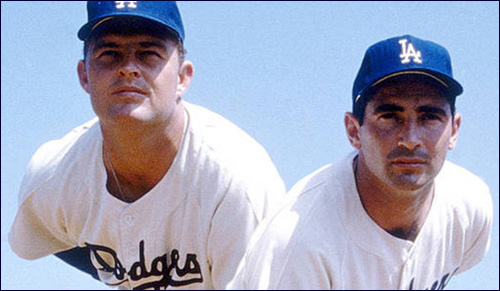

After being pulled from the game, Dodgers pitcher Don Drysdale said, "I bet you wish I was Jewish, too."

The High Holidays are upon us. Today we take a look back at some of the majestic events – from sports, media, to unimaginable sacrifices that took place during Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

Sandy Koufax and Ron Blomberg made an indelible impression when each refused to play ball during the High Holidays. Koufax in particular did so during the World Series. The Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher and Hall of Famer one of the most famous Jewish athletes in American sports, made national headlines when he refused to pitch in the first game of the 1965 World Series because it fell on Yom Kippur.

How many know that when Koufax’s replacement Don Drysdale was pulled from the game for poor performance, he told the Los Angeles Dodgers’ manager Walter Alston, "I bet you wish I was Jewish, too." But 31 years earlier, it was Hank Greenberg who set the bar … and took the greatest risk.

We all know that in 1934, Detroit Tigers first baseman Hank Greenberg who lead the team to win their first American League pennant, decided not to play in a game during a tight pennant race because it fell on Yom Kippur. Edgar Guest wrote of this momentous decision: "We shall miss him on the infield and shall miss him at the bat, but he's true to his religion – and I honor him for that." The Detroit Free Press published a special greeting to him on its front page in 1934 – in Hebrew. The man that Joe DiMaggio called "one of the truly great hitters" – Henry Benjamin Greenberg – born in New York on September 16, 1911, was the first Jew elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1956.

But how many know that “Hammer’n Hank” took an unprecedented and highly risky stand? In “Hank Greenberg: The Hero of Heroes,” journalist John Rosengren tells the story on and off the field. What you may not know is that given the time, anti – Semitism was as rampant in baseball as it was throughout the world. Hank suffered enormous prejudice. Jewish players were routinely baited with Nazi salutes and comments. Notable was Henry Ford’s rantings which included: “American baseball has passed into the hands of Jews” and called on “good Christians to reclaim the national pastime.” When Greenberg embraced his religious and ethnic identity and faced down prejudice, he, according to Rosengren “single – handedly changed the way Gentiles viewed Jews” and “transformed the national pastime into a true meritocracy, a model of democracy.”

Earlier, in 1930, after just ending his rookie stint with the Detroit Tigers, Greenberg returned to his home in the Bronx. Driving in his Model A, he was pulled over for running a red light. Asked by the police officer what he did for a living, Greenberg said that he was a baseball player. The cop peered at his name on the driver’s license and laughed: “Who ... ever heard of a professional ballplayer named Greenberg?”

In short order we all would.

There are countless stories of Jews who, despite enormous risk, still celebrated Judaism’s High Holidays in the horrific early days, and throughout Holocaust. Most remain unsung heroes. Here are two.

From Rabbi Huberband’s diary (published in English under the title “Kiddush Hashem,” edited by Professors Jeffrey Gurock and Robert Hirt): In the aftermath of the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, all public observances of Yom Kippur had been outlawed. Jews debated whether or not they should open their stores, lest they be accused by the Germans of closing them in honor of the holiday.

According to Rabbi Huberband Jewish shopkeepers devised a remarkable scheme to avoid doing business on Yom Kipper while eluding the Nazis’ revenge: “Jews’ shops were open. The ‘salesmen’ were all women. Actually, the women didn't sell anything; people took merchandise, but without paying for it. The women didn't take any money, but they did on the other hand give away money. They took their tribute payments over to the [Judenrat] office, Yom Kippur being the last day, the deadline for the tribute.”

From Prof. Yaffa Eliach’s book Hasidic Tales of the Holocaust: The year was 1944. A Hungarian Jewish slave – labor battalion attached to a retreating German army along the Polish – Slovakian border region, were tortured. On Erev Yom Kippur, the German commanding officer warned them that anyone who fasted “will be executed by a firing squad.” On Yom Kippur, it rained heavily where they were working, and the area was covered in deep mud. When given their meager rations, the Jewish prisoners pretended to eat but instead “spilled the coffee into the running muddy gullies and tucked the stale bread into their soaked jackets.” Those who had memorized portions of the Yom Kippur prayer service recited them by heart until finally, as night fell, they prepared to break the fast. Just then they were confronted by the German commander, who informed them he knew that they had fasted, and instead of simply executing them, they would have to climb a nearby mountain and slide down it on their stomachs. “Tired, soaked, starved and emaciated,” the Jews did as they were told – 10 times “climbing and sliding from an unknown Polish mountain which on that soggy Yom Kippur night became a symbol of Jewish courage and human dignity.”

Eventually the Germans tired of this sport and the defiant Jewish prisoners were permitted to break their fast and live – at least for another day.

And so, on the High Holidays, we rejoice, we repent … we fast and live for another day.

Shana tova