Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

10 min read

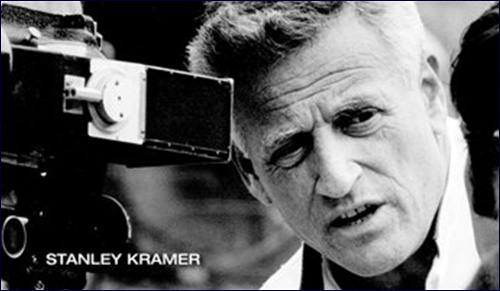

Producer Stanley Kramer was the conscience of a generation.

There’s an old saying in Hollywood: “If you want to send a message, call Western Union.”

Producer-director Stanley Kramer ignored that line.

His timing was ironically impeccable. This was the fifties and sixties. This was an industry that was fighting the new medium, television. Frantic moguls tried rock rock rocking audiences ’round the clock, beguiling them via crab invasions, and invented new techniques from 3-D to Smell-O-Vision to get kids off the sofa and back into these popcorn havens.

To be sure, the fifties and sixties produced many memorable films, yet even many of the “greats” left the messages for Western Union as their talented stars danced beautifully among the raindrops.

Kramer used his films as a weapon.

Not Kramer. He closed those umbrellas, and opened the eyes of his audiences to the storm clouds he saw around him. Swimming against the tide, he used film as a weapon against the uncomfortable stuff such as racism (The Defiant Ones, 1958 and 1967's Guess Who's Coming to Dinner), the futility of a nuclear war (On the Beach, 1959), youth rebellion (The Wild One, 1953). He also hit hot buttons delving into the Jewish perspective, anti-Semitism, and the Holocaust (The Caine Mutiny, 1954; Ship of Fools, 1965; and Judgment at Nuremberg, 1961).

Kramer, who died in 2001, marginalized the “message” moniker of his work seeing himself as "a storyteller with a point of view":

Yet, despite some reviewers who saw many of this “stories” as "shallow, irritatingly self-righteous melodramas," virtually all hailed his courage, taking on themes of social importance; a risky move in a Presley world. Even he would finally have to grudgingly accept the dubious honor of being the moral conscience of Hollywood.

While his work may have angered some (at times he received death threats) most of his 35 pictures won acclaim, receiving 85 Oscar nominations and winning 16 Academy Awards. Kramer received the Irving Thalberg Award in 1961 for his achievements as a producer. In 2002, a year after his death, the Producers Guild of America created the Stanley Kramer Award honoring those films that illuminate provocative social issues.

Provocative he was. Kramer, with undaunting conviction and courage did things his way, early on becoming an autonomous “independent producer” long pre-dating the “Indie” film movement. If he was going to tell a story, it actually had to make a point; "I tried to make movies that lasted about issues that would not go away," he said.

They haven’t. His films have not only stood the test of time, they’ve had an impact on the conscience of the world.

Stanley Earl Kramer was born on September 29, 1913 to Jewish parents, or more precisely to a Jewish mother. His father separated from the family before he was born, leaving his wife and infant son nearly broke in a dingy apartment located in the notorious part of Manhattan known as Hell’s Kitchen. His grandparents watched the precocious boy while his mother worked grueling hours as a secretary for Paramount. His stroke of luck hit during the Depression. Just before graduating from New York University in 1933, Hollywood reps looking for interns read one of his stories, and so he entered show biz. Kramer was sent to Twentieth Century-Fox in California where he moved furniture around sets and wrote material nobody read. At the end of his three month internship, he was stuck in L.A. without train fare back to New York. So the pugnacious young Kramer bet all he had on a horse at Santa Anita – and won.

He stayed, moved more furniture, and shopped screenplays. He finally landed a job as an assistant to independent producers Albert Lewin and David Loew. When Kramer was drafted into the Army in 1943, with Lewin’s help, he was assigned to an army film unit on Long Island where he made training films. Having shlepped enough furniture in Hollywood, he was determined to make his own films. In 1947 Kramer, along with Carl Foreman (later blacklisted) formed their own independent film company.

No doubt the mean streets, and circumstances of his childhood influenced both his art and determination, but it was FDR and the New Deal he credits as giving him a social conscience and focus. “When I made pictures … Roosevelt was in the front of my mind … his concern for the welfare of all Americans. All of this had a tremendous influence on me, not only on which films I made, but on the way I made films and the reasons I made them,” said Kramer later.

His filmography reads like a syllabus in civics and plays like an engrossing reality check with the help of a cadre of talent who worshipped the man for his bold-face chutzpah and his conviction that the United States could make movies that were both entertaining and gave audiences personal “ah” moments. The list of his disciples is extensive and includes among many: Spencer Tracy, Katherine Hepburn, Humphrey Bogart, Cary Grant, Frank Sinatra, Gregory Peck, Fredric March, Richard Widmark, Burt Lancaster, Lee Marvin, Vivien Leigh, Sidney Poitier, and even Marlon Brando, whom Kramer introduced to the world in The Wild One.

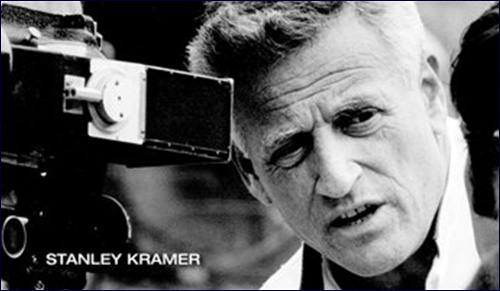

His films about the Jewish point of view, as well as Nazi Germany, specifically Ship of Fools, and Judgement at Nuremberg are of particular interest as while each is dynamic, even harsh, “the messages” are delivered globally, and without exploitation. In these masterpieces, Kramer didn’t “pull” his audience, but fiercely lulled them into awakening.

In Ship of Fools the audience is primed from the first, as brilliant actor Michael Dunn, a dwarf, speaks to viewers directly and acts as a Greek chorus throughout the film, says: "My name is Karl Glocken and this is a ship of fools! I am a fool. You’ll meet more fools as we go along. This tub is packed with them. … Tolerant Jews, Dwarfs. All kinds. And who knows—if you look closely enough, you may even find yourself on board." The film, superbly written by Abby Mann from the Katherine Anne Porter novel, takes us on a voyage as an all-star cast sets out from Mexico to Germany in 1933 – so close and so far from war. The reactions and interactions of the passengers are somewhat metaphoric, as some are happy to be bound for the “motherland,” some are apprehensive, while others appear oblivious to its potential dangers, including the Jew aboard.

In Ship of Fools the audience is primed from the first, as brilliant actor Michael Dunn, a dwarf, speaks to viewers directly and acts as a Greek chorus throughout the film, says: "My name is Karl Glocken and this is a ship of fools! I am a fool. You’ll meet more fools as we go along. This tub is packed with them. … Tolerant Jews, Dwarfs. All kinds. And who knows—if you look closely enough, you may even find yourself on board." The film, superbly written by Abby Mann from the Katherine Anne Porter novel, takes us on a voyage as an all-star cast sets out from Mexico to Germany in 1933 – so close and so far from war. The reactions and interactions of the passengers are somewhat metaphoric, as some are happy to be bound for the “motherland,” some are apprehensive, while others appear oblivious to its potential dangers, including the Jew aboard.

Around it swirl distasteful, ignorant, and pathetic characters—particularly the loud and noxious anti-Semite (played by Jose Ferrer). All are on their way to a destiny they could have stopped.

"There are nearly a million Jews in Germany. What are they going to do—kill us all?"

Prophetically, the Jew aboard scoffs: "There are nearly a million Jews in Germany. What are they going to do—kill us all?"

In Ship, Kramer created a microcosm, displaying a weakness of the world that permitted the rise of Hitler. Kramer has written: "Even though we never mention him [Hitler] in the picture, his ascendancy is an ever-present factor.”

Such is the wealth of reflection upon the human condition in Ship of Fools.

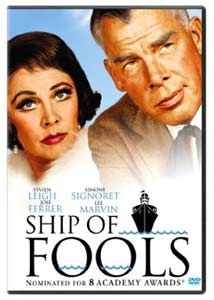

Judgment at Nuremberg (1961) still stands as one of the greatest post-Holocaust films of all time. The unsettling film capsulizes the series of 13 infamous Nuremberg Trials held in 1948; dramatically focusing on Chief Judge Haywood, played by Spencer Tracy (based upon Judge Frances Biddle), and four fictional Nazi judges, notably Dr. Ernst Janning (Burt Lancaster), all who knowingly sentenced innocent men to sexual sterilization, imprisonment or execution for their religions, racial or ethnic identities, political beliefs, or physical handicaps in accordance with Nazi “Law.”

Judgment at Nuremberg (1961) still stands as one of the greatest post-Holocaust films of all time. The unsettling film capsulizes the series of 13 infamous Nuremberg Trials held in 1948; dramatically focusing on Chief Judge Haywood, played by Spencer Tracy (based upon Judge Frances Biddle), and four fictional Nazi judges, notably Dr. Ernst Janning (Burt Lancaster), all who knowingly sentenced innocent men to sexual sterilization, imprisonment or execution for their religions, racial or ethnic identities, political beliefs, or physical handicaps in accordance with Nazi “Law.”

The film was inspired by the Judges' Trial before the Nuremberg Military Tribunal in 1947, which resulted in four of the defendants being sentenced to life in prison. A key thread in the film involves a "race defilement" trial known as the "Feldenstein case." In this fictionalized case based on the real life Katzenberger Trial, an elderly Jewish man was tried for having a relationship with an "Aryan" woman and sentenced to execution by Janning in 1935.

Using this and other examples, plus explicit footage, the movie explores individual conscience vs. “following orders” and loyalty to country in the face of unjust laws, perfidy, and societal amorality.

Like Ship of Fools, the film is most powerful for its subtle and shaded characterizations of both victim and victimizer. Of all the defendants, the scholarly brilliant jurist, Jannings alone, accepts responsibility and confesses in one of the most remarkable speeches of writer Abby Mann’s stellar career.

Janning [Excerpted]: “Where were we? Where were we when Hitler began shrieking his hate in Reichstag? …Where were we when our neighbors were being dragged out in the middle of the night to Dachau?! … Where were we when they cried out in the night to us. Deaf, dumb, blind!! … Because we didn't want to know. … And [I] Ernst Janning, worse than any of them because he knew what they were … who made his life excrement, because he walked with them.”

Ultimately, Haywood has to choose between patriotism and justice, and he rejects the call to let the Nazi judges off lightly to gain Germany's support in the Cold War against the Soviet Union.

Judge Dan Haywood [Excerpted]: The real complaining party at the bar in this courtroom is civilization. ...Janning, to be sure, is a tragic figure. ... This trial has shown that under the stress of a national crisis, men - even able and extraordinary men - can delude themselves into the commission of crimes and atrocities so vast and heinous as to stagger the imagination. … There are those in our country today, too, who speak of the ‘protection’ of the country. Of ‘survival.’ The answer to that is: ‘survival as what’? A country isn't a rock. And it isn't an extension of one's self. It's what it stands for, when standing for something is the most difficult! Before the people of the world - let it now be noted in our decision here that this is what we stand for: justice, truth... and the value of a single human being!”

In a riveting final scene, the convicted Janning asks to see Judge Haywood, pleading not for mercy, but for understanding.

“Those people, those millions of people... I never knew it would come to that. You must believe it, You must believe it!” to which Haywood simply replies, “Herr Janning, it ‘came to that’ the first time you sentenced a man to death you knew to be innocent.”

Coincidentally, the film was released during the Eichmann trial in Israel.

For his indefatigable courage, his ability to hold a mirror to the world, and for his refusal to leave the messages “to Western Union” – messages that are as critical today as they were 60 years ago, Stanley Earl Kramer is a Star of David.