Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

10 min read

Jews go through on dry land, while the Egyptians drown.

Introduction

The miracle of the splitting of the Red Sea is the culmination of the Exodus. One week after the calamitous plague of the First Born, once again Pharaoh is chasing after the Jews to enslave them. As he advances, the Jews are trapped between the sea and the advancing Egyptian army.

Groups of Jews suggest a variety of responses to the impending disaster. God tells Moses to cease praying and travel toward the sea. In a heroic act of faith, Nachshon, prince of the tribe of Judah, throws himself into the sea, and it splits.1

The Jews cross on dry land, pursued by the Egyptians. The sea – with perfect timing – closes back, drowning the Egyptians. The Jews witness the punishment of their oppressors; it is the moment of full liberation.

In an expression of gratitude to God, Moses leads the men in song, and Miriam the women.

In this essay we will explore following issues:

The Exodus Redux

One of the most basic human instincts is the desire to be independent. This is true in a physical sense, as well as a spiritual sense. One who seeks spiritual independence strives for autonomous knowledge and service of God. He is not satisfied with blindly swallowing what he is taught, but needs to reach these conclusions through his own efforts. He is not satisfied with serving God solely guided by others, but wants to prove his allegiance to God independently. This is the process of spiritual maturation.

When the Jewish people left Egypt, they were the spiritual equivalent of children. Their active participation in the Ten Plagues and the Exodus was negligible. The plagues were accomplished in a completely miraculous way through the agency of Moses and Aaron. The Exodus itself was predicated on the covenant that God promised Abraham to redeem his descendants from slavery.2

Therefore, the Jewish people needed to mature and interact with God on their own. This was the purpose of the second phase of the Exodus, the splitting of the sea.

In order to bring the Jews to this degree of independence, God directs them on a specific journey: After traveling into the desert, they make a u-turn toward the mountain of Baal Tzafon in the direction of Egypt. Baal Tzafon is significant as the only remaining Egyptian idol; all the other idols were destroyed in the plague of the First Born.3 This about-face, God says, is to confuse Pharaoh into thinking that the luck of the Jews has run out, that the idol is still in control, and that he can subjugate the Jews once again.4 Pharaoh takes the bait, conveniently forgets the plagues, and gives chase.

Let’s imagine this from the perspective of the Jews: They are finally free, and now they are being told to return back toward the country that enslaved them. Why should they listen?

Amazingly, there was not a murmur or a fight. As one people they turn back toward Egypt, whatever logic may tell them otherwise. The Jews are now active participants in their freedom, choosing to willingly follow God's dictates as transmitted by Moses.

However, when the entire Egyptian cavalry comes onto the scene, their tone changes. An examination the verses shows the varied voices of the Jewish people:

Moses said to the people, “Do not fear. Stand still, and see the salvation of G-d that He will show you today: for the Egyptians whom you have seen today, you shall never see them again. G-d will fight for you, and you shall be silent.”5

The Midrash explains6:

As opposed to the Exodus where the Jews were passive, here their ideas are part of the process. God wants them to reach the right conclusion through their own efforts.

This explains an anomaly. As the Jews stand trapped on the shores of the sea, God tells Moses, "Why are you crying out to me? Tell the Jews to move!"7 Generally, the greatest connection to God is prayer. Why in this case does God does not desire prayer?

Since the Jews had momentarily weakened in their faith in God, prayer for them was not effective. God does not answer prayers of one who does not believe. (At one point, even the angels said to God, "Why are you planning to give the Torah to the Jews? They will be transgressing!"8) Therefore, God tells Moses, prayer is now ineffective.

What the Jews need now is a dramatic demonstration of faith. So Nachshon, the prince of the tribe of Judah, jumps into the sea.9 Once he showed faith in God, and God responded, the faith of the entire Jewish people is restored, strengthened and unified. They thus became worthy of the Exodus on their own merit.

Walking through on Dry Land

Of the many ways that God could lead the Jews to the next level of spiritual freedom, and to eradicate the Egyptians, God chose to split the sea. This is more significant than mere logistics. (Many commentaries even point out that the Jews did not actually cross the sea, but entered and exited on the same shore!)10

In order to understand this event, we need to go back to Creation. The story of Genesis begins with God creating a world covered in water and darkness. To set the stage for man to dwell on Earth, God gathers the waters into seas, and dry land appears.11

The creation of the Jewish people parallels the creation of man. There is a need to set the stage for the 'land' of the Jewish people. It is not sufficient to just go free from Egypt; they must be raised to a different level of existence. Therefore God reenacts the creation, but with the Jews as the central characters. From this point, the Jews are called 'Ivrim', those who crossed the sea.12 That is why walking on dry land is more crucial than actually escaping across the sea.

The drowning of the Egyptians is to illustrate another of God's attributes: the consequence of ‘measure for measure’ (mida keneged mida). This is not a vindictive punishment, but rather a logical means by which we understand God's interaction with man. In the absence of prophecy, the reward or punishment itself serves as God's messenger.

What is the ‘measure for measure’ in this case? Since the Egyptians began oppressing the Israelites by throwing their male children into the Nile, the finale is that the Egyptians should drown. And to emphasize the exactitude of the punishment, each Egyptian sank at a rate precisely equivalent to his own participation in the persecution of the Jews (i.e. a harsher oppressor sank more slowly).13

Song and Redemption

The idea of a song at this point seems difficult to understand. On one hand, there was a miraculous delivery of the Jews from certain enslavement and possible death. On the other hand, was it appropriate to celebrate the destruction of the Egyptian nation?

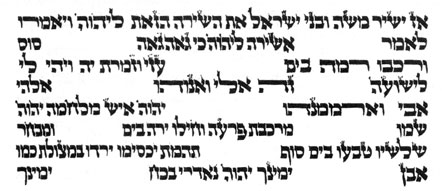

If one looks at a Torah scroll, the section of the “Song of the Sea” is written differently than the rest of the Torah. Normally, a section of text is broken by short white spaces to separate different ideas. But here, the text is written in the form of a brick wall: two short blocks of text at opposite ends of the line, followed on the next line by a longer block of text supporting them. Why does the song require all this white space?

The effect is a large amount of white space interspersed in the text. The purpose of the white space, indicating an intermission, is to allow the student time to digest the material.14 For the Jews, the Egyptian exile was not a punishment but a learning experience. However, during the exile itself the lessons were unclear. Why are we suffering, and what is the purpose, if any? Thus the redemption is not only physical but also conceptual; we now understand what we were supposed to learn.

A song is different than speech in its intonation. Speech is much more monotonous; song goes up and down in speed and tone. This song is the proper finale to the exile. What is being celebrated is not the downfall of the enemies, but the realization that the ups and downs of the exile are themselves part of one whole. The symphony of Jewish history is not always easy to understand, so there needs to be more white space, to allow us to digest the lessons of the exile and integrate them into one unified whole, showing God's loving and guiding hand.

The song is not in an exultant revengeful sense. In fact, when the angels desired to sing to God after the drowning of the Egyptians, God angrily quiets them: “My handiwork is drowning in the sea – and you desire to sing!?”15

If so, why are the Jews allowed, and even praised, for singing?

The issue is: Who is singing? The song of the angels is an abstract praise of God. That is inappropriate when it comes in conjunction with an act of punishment. But the song of the Jews is personal; they recognize God’s interaction with them and see His hidden hand through their history. Therefore, at the completion of the Exodus, song is appropriate.

Miriam's Song

Upon exiting the sea, Miriam led the women in song and dance with musical instruments.16 Why did these Jewish slaves, who were escaping post haste from their masters, trouble themselves to bring musical instruments?

During the harsh slavery in Egypt, there was one segment of the Jewish nation that did not give up: the women. They constantly raised the morale of the men, by assisting their husbands after a full day of slave labor.17 Yocheved, the mother of Moses, and Miriam his sister, even stood up to the mighty Pharaoh himself: As the midwives (Shifra and Puah), they rejected Pharaoh's demand to murder the Jewish boys as they were born.18

The faith of the Jewish women remained strong. Therefore, when they left Egypt, they were sure that more miraculous events would take place. In anticipation, they brought along musical instruments.

The strength of Jewish women has sustained our people for millennia. And just as the redemption from Egypt was in the merit of Jewish women, so too will the future, final redemption.19