Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

17 min read

Understanding the origins and purpose of the Five Books of Moses.

The Five Books of Moses

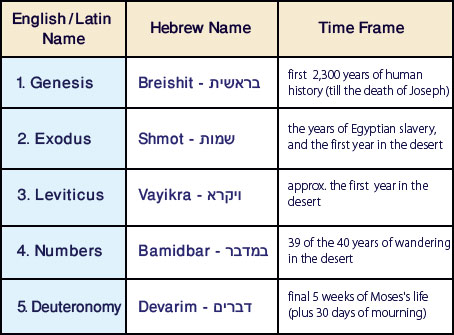

In Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses is called the Chumash – shorthand for Chamisha Chumshei Torah, which literally means the "five-fifths of the Torah."

And while the term "Torah" can refer to the entire body of Jewish thought, it often refers to just the Chumash.

The Chumash is also known as Pentateuch, a Greek word ("pent" means five; "teuch" means book). Bible is also a Greek word, meaning "book." The first translation of the Bible was into Greek, in the third century BCE, when Ptolemy II coerced 72 rabbis to do the translation.1 It is thus called the "Septuagint," which means "seventy."

The Chumash is called the Five Books of Moses because God dictated the entire text to Moses, who wrote it down. The five books are divided into 54 sections, and one section (called a parsha) is read every Shabbat in the synagogue. (Occasionally, two portions are read together.)

Because the Chumash is the basic book of Judaism, it is essential to have a good overall grasp of its content. This course features an illuminating essay on each of the 22 key Chumash themes, written by Rabbi Zave Rudman, an educator in Jerusalem with 25 years of experience teaching Chumash. (Rabbi Noson Weisz of Jerusalem is guest author for two of the essays, "Purpose of Creation" and "Binding of Isaac.")

In addition, each of the 22 Chumash themes features a 3-minute video presentation by Rabbi Eytan Feiner, a popular international speaker and a senior lecturer at Aish HaTorah in Jerusalem.

Here are the Five Books of Moses, with a brief description, and a distributive breakdown of the syllabus for this course:

(1) The Book of Genesis (Bereishit) deals with the origin of the world, the history of the world prior to and including the forefathers of the Jewish people, and the spiritual development of the Jewish people up until the era of Egyptian slavery. Essays in this section of the course include:

Class #2 – Purpose of Creation

Class #3 – Garden of Eden

Class #4 – Noah's Flood

Class #5 – God's Covenant with Abraham

Class #6 – Binding of Isaac

Class #7 – Jacob-Esav Rivalry

Class #8 – Story of Joseph

(2) The Book of Exodus (Shmot) includes the account of Jewish slavery, Moses' rise to the role of leader, the awesome events of the Exodus, and the seminal first months in the Sinai desert. Essays in this section of the course include:

Class #9 – Moses: Prophet and Leader

Class #10 – Ten Plagues

Class #11 – Splitting of the Red Sea

Class #12 – Ten Commandments

Class #13 – Golden Calf

Class #14 – The Tabernacle

(3) The Book of Leviticus (Vayikra) is named for the Levites, the tribe from whom the Jewish priesthood (kohanim) emerged. The Levites were responsible for assisting with the service and maintaining the Tabernacle (and later the Holy Temple in Jerusalem). The major topic of this book is the kohanim, descendants of Moses's brother, Aaron, who performed the actual Temple service. Jewish tradition often refers to this book as Torat Kohanim, "the laws of the priests." Essays in this section of the course include:

Class #15 – Understanding Korbanot

Class #16 – Holiness & Love Your Neighbor

Class #17 – The Jewish Festivals

(4) The Book of Numbers (Bamidbar) is so called because it begins with a census of the Jewish population in the desert. In Hebrew, this book is called Bamidbar – "in the desert" – as it chronicles the bulk of the 40 years of Jewish wandering in the desert en route to the Land of Israel. Essays in this section of the course include:

Class #18 – Sin of the Spies

Class #19 – Korach's Rebellion

Class #20 – The Balak-Bilam Duo

(5) The Book of Deuteronomy (Devarim) is a repetition of many concepts taught in earlier books. This book covers the final 36 days2 of Moses's life, and ends with an account of Moses's own death, as the next generation of Jews are poised to enter the Land of Israel, under the new leadership of Joshua. Essays in this section of the course include:

Class #21 – Wars of the Jews

Class #22 – Tochacha and Teshuva

Class #23 – Transfer of Leadership: From Moses to Joshua

And to review:

Purpose of the Bible

Much has been written about the very purpose of the Chumash: Is it a history book, a book of ethics, or a book of laws? In fact, as the #1 best-selling book every year for the past 3,300 years, it is all this and more. Let's explain:

(1) Law Book

Perhaps most obviously, the Chumash is a book of law. The word "Torah" itself means "instructions" – i.e. it contains every important law and concept necessary for proper Jewish personal and communal life. It is said that Torah is the "constitution" of the Jewish nation. The ideals of Shabbat, tzedakah, the centrality of Israel – in fact all of the 613 mitzvot are contained within.3 Without this book, Judaism would not exist.

(2) History Book

Yet the Chumash is more than just a dry listing of the 613 mitzvot; there are dozens of stories interspersed throughout. So in one regard, the Chumash also serves as a history book, a chronology of events of the first 2,500 years of human existence.4 In many instances, the Torah takes great pains to record accurately names, places and events; entire chapters are listings of names and generations. As the verse says: "This is the book of the chronicles of mankind" (Genesis 5:1).5

(3) Book of National DNA

Yet the Chumash still omits a great many details. For example, when Abraham first appears in the Book of Genesis, he is already 75 years old.6 He is one of the most significant figures in Jewish history and yet the Torah skips over his childhood and adult years.7

So obviously, those stories that are included must have a special purpose beyond their historical value.

There is a concept called Ma'aseh Avot Siman l'Banim8 – "the deeds of the ancestors are a sign for the children." On a macro-cosmic level, events that occurred to the patriarchs and matriarchs are a model for all of Jewish history. This is why we have to pay extra special attention to what's going on at this early phase of the Bible, because here is where the patterns are set. The events in the Torah create spiritual realities – the DNA, as it were – which persist throughout Jewish history. For example, the Jacob-Esav rivalry persists until today as one of the primary sources of anti-Semitism.9 In other words, "History repeats itself." Or in theological terms, Jewish history is Jewish destiny.

(4) Book of Wisdom

Beyond this, each incident in the Torah offers invaluable insights into human behavior. The Bible is often called Torah Chaim10 – literally "Instructions for Living." We derive lessons in behavior from the stories, which help guide and direct our lives. Torah is an inexhaustible source of wisdom that teaches us how to view the world – how to have better relationships, how to achieve peace of mind, how to relate to the world at large.

And while Torah values may occasionally seem irrelevant in light of the modern world, the opposite is actually true. Although many external aspects of society have changed over time, basic human nature has not. Unlike any other self-help book, Torah is a time-tested, proven formula, benefiting from thousands of years of meticulous analysis and practice. Its lessons are timeless. For while contemporary values are of human origin and transient, those of the Torah are divine and eternal.11

(5) Kabbalah Book

There is a deeper layer to the Chumash as well. The Midrash says that "God looked into the Torah and created the world."12 Just as an architect first draws up plans, and the builder produces the physical structure, God first wrote the Torah and then created the world using the Torah as its plan.13 In other words, Torah is the cause and the world is the result. As such, if Torah would cease to exist, the world would cease as well.14

Each detail of the world exists because the Torah says so. As the Vilna Gaon15 wrote:

The rule is that all that was, is, and will be until the end of time is included in the Torah from "Bereishit" (the first verse of Genesis) to "L'eynei kol Yisrael" (the last verse of Deuteronomy). And not merely in a general sense, but including the details of every species and of each person individually, and the most minute details of everything that happened to him from the day of his birth until his death.16

The most seemingly trivial passages and variations in the Torah text contain many secret meanings and lessons. Even as small a mark as a serif on the Hebrew letter yud, or decorative markings, were put there by God to teach scores of lessons.17

The Torah contains many coded messages as well. As the great kabbalist, Rabbi Moshe Cordevaro,18 wrote:

The secrets of our holy Torah are revealed through knowledge of combinations, numerology (gematria), switching letters, first-and-last letters, shapes of letters, first- and-last verses, skip-letters sequences, and letter combinations. These matters are powerful, hidden and enormous secrets.19

It is said that "Torah is the mind of God."20 If we want to connect with our Creator, we must understand His book.

How and When

The Torah was given at Mount Sinai in the Jewish year 2448 (numbered from creation),21 or 1313 BCE. The Torah was dictated by God to Moses – letter by letter, word by word. Moses wrote the Torah very much the same way that a scribe writes today – with pen and ink, on parchment in the form of a scroll.

Many people ask: How do we know the Torah is true. Especially given the central importance of Torah to Jewish life, it is crucial to be able to establish the veracity of the Torah as an accurate and truthful document. There are many excellent writings on this topic. For an in-depth treatment, we recommend Permission to Receive by Lawrence Keleman (Feldheim.com), which presents four rational approaches to the Torah's divine origin. A more concise presentation is, Did God Speak at Sinai?, online at Aish.com.

Throughout all generations, great care was taken to preserve the Torah exactly as it was given to Moses. Since every Torah must be letter-perfect, it is forbidden to write a single letter without copying it from another Torah. Moreover, the scribe must repeat every word out loud before writing it down, so as to insure accuracy in copying.22 This procedure of writing a Torah scroll was repeated countless times throughout the ages by qualified scribes, ensuring the integrity of the Torah for over 3,300 years.

When was the Torah actually written down? Just before the revelation at Sinai, Moses wrote everything that had transpired up until that point.23 After this, God would dictate each passage, Moses would repeat it aloud, and would then write it down.24 At the end of the 40 years of wandering in the desert, after God had finished dictating the entire Torah, Moses bound them together into one scroll.25

The Torah was never written with punctuation, although its sentence structure was revealed to Moses and transmitted, along with the notes used in chanting the Torah.26

Before his death, Moses wrote out 13 Torah scrolls. Twelve of these were distributed to each of the Twelve Tribes. The thirteenth was placed in the Ark of the Covenant with the stone tablets. If anyone would come and attempt to rewrite or falsify the Torah, the one in the Ark would "testify" against him. Likewise, if he had access to the scroll in the Ark and tried to falsify it, the distributed copies would "testify" against him.27

Today we see the fruits of this system. Torah scrolls from across the planet – from Yemen to Russia, from Egypt to Australia – have proven amazingly accurate with virtually no variances.28 This gives us confidence that the Torah we have today, is the same text received at Sinai.

Oral Law

It is a foundation of Jewish belief that the entire Torah, both written and oral, was revealed to Moses by God. The Written Torah lists the commandments, and the Oral Torah explains how to carry them out. Many Jewish laws are not directly mentioned in the Torah, but are derived from textual hints, which were expanded orally. For example:

Totafot (better known as Tefillin) are mentioned in the Bible: "And you shall place totafot between your eyes."29 But how do we know what they are? What color are they? What size? Shape? What about the straps? How many compartments? What parchments go inside? How should they be worn? Who should wear them? When?

None of this is written in the Bible. For these important details, we need the Oral Torah. And there are many such cases.

Rabbi Samson Rafael Hirsch30 explains:

The Written Torah is to the Oral Torah, just as short notes are on a full and extensive lecture on any scientific subject. For the student who has heard the whole lecture, short notes are quite sufficient to bring back afresh to his mind at any time the whole subject of the lecture. For him, a word, an added mark of interrogation or exclamation, a dot, the underlining of a word, etc. is often quite sufficient to recall to his mind a whole series of thoughts. For those who had not heard the lecture from the Master, such notes would be completely useless. If they were to try to reconstruct the scientific contents of the lecture literally from such notes they would of necessity make many errors.

Yet why do we need an Oral Torah? Why wasn't everything just written down?

Torah is not a reference work made to sit on a shelf. It is meant to be lived and internalized. The oral give-and-take, from teacher to student, encourages us to discuss and clarify, to know it backward and forward. And thousands of people learning the same information guarantees that mistakes do not enter the transmission.

Almost 2,000 years ago, the Romans captured Jerusalem and sent the Jews into exile. The president of the Jewish people, Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi, saw that the teacher-student framework was in danger of being disrupted, so he wrote down the Oral Torah – the Mishnah – to avoid it being forgotten.31

As the generations passed, more information – the Talmud – was written down to explain the Mishnah. Today, the basic laws are published in the Code of Jewish Law (Shulchan Aruch) and its accompanying commentaries. But much of Torah is still preserved in oral form, passed from teacher to student.

God, in His infinite wisdom, devised the consummate system for transmitting Torah throughout the generations. It is not a written law, and it is not an oral law. It is both.

English Translations

Hebrew is a very special language. It is the language that God spoke when creating the world.32 As the national language of the Jewish people, it best captures the meanings of Jewish life, concepts and prayers. And of course, Hebrew is the original language of the Torah.

When the Torah is translated into other languages, it loses much of its essence. For instance, the familiar King James translation often diverges from Jewish teachings. Furthermore, our Sages teach that "every day the Torah should be as new."33 This can also means that archaic language should not be used in translations, because this would give the impression that the Torah is old, not new.

Although many "modern" translations are more readable, they are often even more divorced from traditional Judaic sources. They may ignore the Talmud and Midrash, which contain the tradition for how to translate the idiomatic language of the Torah.

Two modern translations are "Jewishly accurate" and highly recommended:

ArtScroll Stone Chumash (ArtScroll.com)

Of course, there is no substitute for learning the original Hebrew text. Hebrew, as God's holy language, has an enormous amount of subtlety that no translation can ever convey. For example, the Hebrew word for "human" is adam. The name itself is derived from the word adama, meaning "ground," from which the first person was created.34 It is also a composite of the word dam, which means blood, and the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, aleph, which always alludes to God.35 This teaches us that a human being is a composite of physical matter and a spiritual soul.

So while it is important to have a good translation on hand, it is equally important to make an effort to study Torah in its original language.

And now... on with the 22 key Chumash themes!