Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

3 min read

4 min read

4 min read

11 min read

Our connection to the land has similarities to our connection to God.

Exile; difficulty farming; hiding from God. What's the common theme?

We can begin by doing a little consolidating. As we noted earlier, the Torah seems to treat exile and difficulty farming as dual expressions of a larger idea -- the advent of a certain distance between man and land:

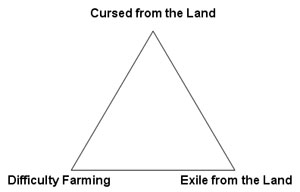

And now, cursed are you from the land that opened its maw to take your brother's blood from your hands. When you work the land, it will no longer give its strength to you; a wanderer shall you be in the land. (Genesis 4:11-12)

We can think of these words as forming a kind of triangle. The fact that Cain is cursed from the earth -- distanced from the land -- is the top of the triangle, the "topic-sentence" as it were. The two points at the base of the triangle then clarify what this "distance from the land" means in real life: It means that you will experience difficulty farming and exile. These two things express a kind of alienation Cain will feel with respect to the land.

We can now go back and simplify our query. Having seen the unifying theme in "difficulty farming" and "exile," we are now looking for common denominators between two elements, rather than three. We now want to know: What does "distance from the earth" and "hiding from God" have in common?1

Well, the ideas of "hiding" and "distance" are certainly similar. When one hides from someone else, one is avoiding contact with them, creating distance. Let's now ask: What, if anything, do "earth" and "God" have in common?

At first glance, you might answer that "earth" and "God" could not be more different. One is the Master of the Universe; the other, a part of that universe. One is the most powerful Being that exists; the other, a mere inanimate object.

But there is a similarity. We get a clue to it from the anguish Cain feels at the prospect of alienation from both these entities, God and land, "My sin is greater than I can bear. Here, you have cast me away from the face of the land, and from Your face I will hide" (Genesis, 4:13).

We mentioned earlier that the verb for "cast away" is the same as the Hebrew word for divorce -- geirashti. Something personal is happening here: The land, like God, is an important being in Cain's life, and somehow, Cain is banished from beholding the "face" of both these beings, "You have cast me away from the face of the land, and from Your face I will hide."

Why is all this so personal?

Let Us Make Man

Some earlier verses will help us out here, I believe.

Back in the beginning of Genesis, when mankind is first created, the Almighty uses a curious turn of phrase. "Let us make man...," He declares. Over the ages, Biblical commentators have struggled to understand the use of the plural here. Who was God talking to when He said "us?"

Christians, as one might imagine, tend to see this as alluding to different facets of God which they call "the Trinity." Judaism, which sees God as an indivisible oneness, has never been much of a fan of the Trinity idea, and Jewish commentators have seen the verse quite differently. Rashi suggests that perhaps God was speaking to the angels. The 13th century Spanish sage Nachmanides has a particularly fascinating interpretation. In an eerie harbinger of modern Big Bang theory, he writes the following:

It was only on the first day of creation that God created something from nothing. From then on, He fashioned everything from the elements He had brought into being on the First Day. For example, He empowered water to give rise to living things, as it is stated "let the water swarm...," and He allowed animal life to emerge from the land, as the verse states: "Let the land bring forth living things (Genesis 1:23)." When He created man, though, the Lord said: "Let us make man...." In so doing, the Almighty was speaking to the earth -- the last "being" to bring forth life [see the immediately preceding verse about earth "bringing forth" the animals]. In effect, He was saying: "You and I together will make man. You will contribute the elements for the body, as you did for the animals, and I will contribute the soul, as it is written: ‘and He breathed into his nostrils the breath of life.'" (Nachmanides to Genesis 1:26)

Men will fight and die for land, and will form intense emotional bonds to the ground they call home. Why?

The implications of Nachmanides words are astounding, and not just for the way in which he seems to anticipate the direction of modern biology, seven centuries before Pasteur, Darwin and Mendel were even a gleam in history's eye. Nachmanides is suggesting here a key to the mysterious connection between man and land. Men will fight and die for land, and will form intense emotional bonds to the ground they call home. Why? Because, at the end of the day, land is not a mere "thing." It, along with God, is the source from which we come. And because of that, it will always matter personally to us.

A creature always wants a relationship with its creator. We long to live in harmony with our parents, for, as Dorothy famously said, "there's no place like home." On some level, it is to both land and God that mankind longs to return -- a dream that ironically, is perhaps fully realized only in death, "Dust you are, and to the dust you shall return" (Genesis 3:18). "The dust [that comprises the body] shall go back to the land, as it once was; and the spirit will return to the Lord who had imparted it" (Ecclesiastes 12:7).

Cain, God and Mother Earth

It is no coincidence that we call land, "Mother Earth," for she provides mankind with the essential gifts of femininity: nourishment and a safe place to be; a place to call home.

A mother provides a safe environment for her family. This is true not only physically, but emotionally. A home, at its best, is a place where children need not fear the caprice and unpredictability of the outside world. Likewise, a mother provides nourishment -- not only physically, but emotionally. She provides not just food but love -- nurturing her offspring and helping them grow into stable and happy human beings.

A woman gives these twin gifts, nourishment and a place to be, not just to her fully developed family, but to her developing family as well. She gives them at the very beginning, through the organ that is the embodiment of femininity, the womb. For what does a womb provide for the fetus ensconced within it? It provides total nourishment, as well as a perfectly calibrated "safe place to be," an environment completely insulated from the shocks of the outside world.

Mother earth provides these gifts to her children, too. She provides us with a place to be, a home in which we can live, and she also provides us with nourishment -- the agricultural bounty of her fertile soil.

Cain, in the wake of Abel's murder, finds himself distanced from both these aspects of land, and he finds himself hiding from God. Having failed to give his all to his own Creator, he becomes aware that Mother Earth will no longer give her all to him, "When you work the earth, it will no longer give its strength to you" (Genesis, 4:11).

Instinctively, Cain knows exactly what this means. It is a punishment greater than he can bear: He has been "cast away" from the "faces" of Mother Earth and from the Almighty, becoming painfully out of touch with his ultimate creators.

At long last, we can go back and plot the continuum of these narratives, the sagas of the Tree of Knowledge and of Cain and Abel, and we can see how they integrate, almost seamlessly, into one story.

From Forbidden Fruit to Murder

As we saw earlier, when Adam and Eve ate from the Tree of Knowledge, they brought the creative will inside of them more powerfully than ever before. In so doing, they became "godly," after a fashion, "and you shall be as gods, knowing good and evil."

But they were only "half-godly." They were passionate; driven, like God to create and foster new life -- but, unlike God, their ability to properly steer this newly fired sense of creativity remained limited, and out of proportion with its power.

The Creator of All understands that the world needs not just life, but death at the appropriate time as well.

God's creativity is inherently disciplined. The Creator of All understands that the world needs not just life, but death at the appropriate time as well. When a baby develops in the womb, its hands begin as a kind of formless paddle. Fingers are formed only because skin cells between each of the digits are programmed to die and fall away, sculpting what we call a hand in the inky blackness of the womb. Death in the service of life is painful and sad -- but sometimes necessary. A disciplined creator works with death as well as life, sculpting with exquisite care everything from galaxies, to ecosystems, to babies.2

As a consequence of eating from the tree, man is powerfully creative, but the question is: Can he also be disciplined? The possibility that the answer to this might be negative has many consequences. Adam and Eve become immediately fearful of their nakedness; aware the raw power of sexuality could crush them. Moreover, man -- possessor of unbridled creativity -- finds himself distanced from his own creators, God and land. Finally, mankind flounders as well with their own ability to create: In the wake of the Tree of Knowledge, pain in childbirth is brought into the world for the first time.

The very next story in the Bible, the saga of Cain and Abel, picks up where the previous episode left off. For after eating from the Tree of Knowledge, the great question facing mankind is: How, in fact, will we steer the fearsome force of creativity that beats so insistently inside us? Cain must ask himself: Will he be ruled by his passion to create -- will he sacrifice his relationship with God on that altar? Or will he rule over that passion, and enhance his relationship with God instead?

In failing to meet this challenge, in failing to guide the inherently blind creative will he possessed so richly, Cain suffers an intensification of the consequences felt by his parents. He, like Adam, is alienated from his creators -- but more permanently so. He intuits that he shall not merely hide from God momentarily, but shall spend his life in that state of hiding [...and from your face I will hide]. Likewise, he suffers a more profound alienation from mother earth -- a complete inability to find a home on her soil, and utter frustration in reaping the nourishment she can provide.

From Cain's World to Our World

Cain fails. But his story is not over, "Its desire is unto you, but you can rule over it."

Cain did not listen to what God had to tell him. But the words of that speech were not wasted. Cain's predicament is timeless, and the struggle to deal with creativity and to somehow channel its force constructively -- this challenge is with us as much today as it was then. The words of God's speech to Cain, preserved timelessly in the Torah, speak to us as well as to the original recipient of that message. Perhaps, centuries and millennia later, we can find it within ourselves to listen to them.

1 This perspective is confirmed by a later verse in which Cain summarizes his punishments using the following language: My sin is greater than I can bear. Here you have cast me away from the face of the earth and from the face of God I will hide. In Cain's view, it is about two things: Distance from land and distance from God.

2 In the Jewish tradition, God is associated deeply with the concept of "truth" (e.g. "the seal of the Almighty is truth" -- see Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Shabbos, 55a). In Hebrew, the word "truth" is spelled aleph, mem, tav. Its very structure suggests the idea of balance between life and death.

Aleph is the first letter of the alphabet; mem is the middle letter of the alphabet; and tav is the last.

The first and middle letter of the word spells "em," which means "mother." The middle and last letters o the name spell "met," which means "death."

The seal of God is truth -- disciplined creativity. "Emet" suggests the exquisite balance between motherhood, the intense drive to foster life, and "death," which imposes discipline on raw life and makes something meaningful out of it.