Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

9 min read

Jewish tradition maintains the Romans were descendants of Esau, the bloodthirsty brother of Jacob.

Before we tell the story of how the Second Commonwealth of Israel met its sad end at the hands of the Roman Empire, let us step back in time and delve into what Rome was about, and how it became a power that challenged the mighty Greeks.

Rome started out as a city-state, dating its history to 753 BCE. The founding of the city is rooted in a famous legend:

It was common practice of the settlers of the banks of the Tiber River to keep "vestal virgins" on whom they believed their fate rested. These young women had to stay pure and chaste, and if any vestal virgin strayed, she was put to death by being buried alive.

According to this legend, in the 8th century BCE one vestal virgin, named Rhea Silvia, found herself pregnant. But she got pregnant through no fault of her own ― she was raped by the god Mars.

(Here we have a familiar story, that predates the Christian one by some 800 years ― a woman who has a physical relationship with a god, ergo est, as they say in Latin, she remains a virgin yet she gives birth.)

Rhea Silvia gave birth to twins ― Romulus and Remus ― but the local king, jealous of their semi-divine status, had them thrown into the Tiber River. Miraculously, they floated ashore, were nursed by a she-wolf, and then reared by a shepherd.

When they grew up, these boys established the city of Rome on seven hills overlooking the Tiber, near the very place where they had been rescued from drowning. (Later Romulus killed Remus and became the god Quirinus.)

Interestingly, Jewish tradition holds that the Romans were the descendants of Esau, the red-haired and blood-thirsty twin brother of Jacob. Judaism calls Rome "Edom", (another name given Esau in Genesis 36:1) from the Hebrew root which means both "red" and "blood." When we look at the Jewish-Roman relationship later on, we will see that the Romans were the spiritual inheritors of the Esau worldview.

Roman Republic

If we skip ahead a few hundred years from the time of Romulus, we find that circa 500 BCE the residents of Rome have overthrown the monarchy ruling them and have established a republic ruled by a senate. An oligarchy, the senate was made up of upper class, land-owning male citizens called the "patricians."

As any healthy and strong ancient civilization, the Romans went to war to expand their sphere of dominance. Roman ambitions met the like-minded Carthaginians, unleashing a titanic struggle known as the Punic Wars, which lasted from 264 to 146 BCE, and in which Rome was victorious.

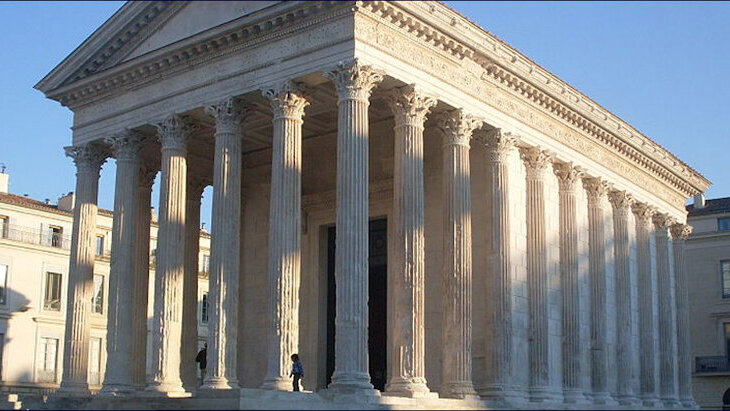

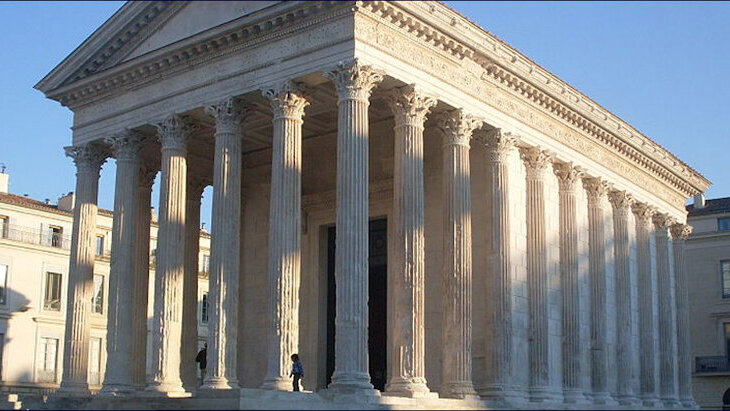

The Romans went on to conquer the Greek colonies and Greece itself, and to become the great power in the Mediterranean. To a large extent they inherited the Greek view of the world. We call their culture Greco-Roman because ― although Greece and Rome were two different peoples, different civilizations and different cultures ― the Romans to a very large extent viewed themselves as the cultural inheritors of the Greeks.

Later on in Roman history, many Romans will view themselves, literally, as the reincarnation of the Greeks. The Greeks influenced roman architecture and much of the Roman worldview in many respects. But the Romans made their own contributions as well.

For one thing Rome was much more conservative, patriarchal society than Greece was. The Romans were also very hard-working and extremely well organized, and this is what made them masters of empire-building.

We see their ability to organize in all spheres:

Roman Conquest

The Romans revolutionized warfare. Unlike the Greeks, they did not conscript citizens; Roman evolved into the world's first professional army. Their soldiers were paid to fight, and they made a lifelong career of it. Soldiering for Rome was not just a job ― it was a way of life and a commitment which lasted for twenty five years. The Roman motto was captured in a famous saying of Julius Caesar, arguably Rome's greatest general: Veni, vidi, vici ― "I came, I saw, I conquered."

Because they made a career of fighting, Roman soldiers were extremely well trained and very disciplined in battle. And they were also extremely well equipped. The art of warfare was perfected through constant drilling and tactical training, discipline and state-of-the-art military technology. This gave the Romans a huge advantage in battle that was unparalleled in human history.

Instead of the big, unwieldy Greek phalanxes that could not move quickly, the Romans created what they called legions, each of which was subdivided into 10 smaller and more mobile cohorts. The legion became the basic unit of the Roman army. The Romans would have between 24 and 28 legions, each with about 5,000 men plus and equal number of auxiliary troops, mostly infantry with a little cavalry.

The organizational structure of the legions gave the Romans tremendous flexibility on the battlefield. The smaller units (cohorts) that comprised each legion could maneuver independently in ways that the Greek phalanx could never do.

This is how the Romans chewed up the Greeks. They simply slaughtered them like they slaughtered everyone they encountered.

This brings us to another key feature of the Roman culture. Although the Romans were very sophisticated people, they were also very brutal, perhaps the most brutal civilization in history.

Their brutality can, of course, be seen in their warfare. They were an incredibly aggressive people, a people with seeming unbridled ambition to conquer everything. (This fits with the Jewish understanding of the descendants of Esau, who was gifted with the power to dominate physically; whereas Esau's twin-brother Jacob was gifted with the power to dominate spiritually.)

But even more strikingly, their brutality can be seen in their forms of entertainment. At 200 different locations throughout the empire, the Romans built amphitheaters where they would spend the day, eating, relaxing and watching people be grotesquely butchered. (The practice was extremely popular and Emperor Augustus in his Acts brags that during his reign he staged games where 10,000 men fought and 3,500 wild beasts were slain.

This points out a very interesting lesson in human history. We often will find the most sophisticated cultures, despite their sophisticated legal systems, being the most brutal. You see it with Rome (and later with many others, most recently with Nazi Germany).

Roman Empire

While the Roman armies were mightily victorious abroad, the republic wasn't doing so well at home.

In the 1st century BCE, Rome had to contend with internal strife and class struggle - of which the slave revolt led by Spartacus (72 BCE) is perhaps the most famous. The so-called "Social War" forced Rome to extend citizenship widely, but the republic was nevertheless doomed.

The general, Pompeii emerged as a popular champion and found allies in Crassus and Julius Caesar, forming the First Triumvirate in 60 BCE. But within ten years Pompeii and Caesar fell out, with Caesar becoming the master of Rome and laying the foundation for the Roman Empire.

This is the point in time where we left off the story back in the land of Israel.

The last two Hasmonean rulers (from the line of the Maccabees) were two brothers: Hyrcanus and Aristobolus. Quarreling with each other as to who should be king, they hit on the idea of asking Rome to mediate in their dispute. And thus, in 63 BCE, Pompeii was invited to move his armies into Israel.

Josephus, the great first century CE Jewish historian, explains what happened next in great detail.

The Romans came in, slaughtered many Jews and made Hyrcanus, the weaker of the two brothers, the nominal puppet ruler of the country.

This was part of the Roman system. They liked to rule by proxy, allowing the local governor or king to deal with the day-to-day problems of running the country, as long as the Roman tax was paid and Roman laws obeyed!

Roman intervention in Israel had effectively ended Jewish independence and ushered in one of the bleakest periods of Jewish history. Rome ruled, not Hyrcanus, or any Jew for that matter. (The Sanhedrin's authority was abolished by Roman decree six years after Pompeii's conquest.)

The independent state of Israel ceased to exist, and became the Roman province of Judea. Pompeii split up much of the land giving large chunks to his soldiers as a reward for their prowess in battle. Gaza, Jaffa, Ashdod and other Jewish cities were now a part of the map of the Roman Empire.

Hyrcanus, though he might call himself king, got only Jerusalem, along with a few pieces north and south, but even this small area he could not govern without checking in with the Roman proconsul in Damascus.

A key role in the Roman takeover of Israel was played by Hyrcanus' chief advisor ― the Idumean general Antipater. The Idumeans bore testimony to an unprecedented lapse in observance among the Jews ― they were the people whom Yochanan Hyrcanus forcibly converted to Judaism.

Antipater, the real strength behind the weak Hyrcanus, made sure, of course, that he positioned his own family in power while he had a chance. He continued to guide Hyrcanus and ― when in 49 BCE, Pompeii and Julius Caesar became engaged in internal struggle ― helped him choose the winning side. Soon, Antipater was the man in power.

The Romans judged correctly that this forcibly converted Jew did not identify with Jewish values or nationalism, and that with him in power, "militant monotheism" would not again rear its dangerous head.

While Antipater did not go down in history as a household name, his son Herod ― who took after his father and then some ― did. Coming from a family of forced converts that was only nominally Jewish, he nevertheless became one of the most famous kings of the Jews.

He went down in history as Herod, the Great.