Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

9 min read

The Europeans didn't know what caused the bubonic plague, but had no trouble blaming the Jews.

In the 14th century the bubonic plague ― known as the "Black Death" ― hit Europe. At that time, people had no idea of the causes of diseases and no idea that lack of hygiene caused the spread of bacteria.

Some historians have cynically pointed out that bathing defined the difference between the Classical Age and the Dark Ages. The Greeks and Romans were very clean people and public baths were everywhere. Medieval Europeans, on the other hand, didn't bathe at all. Sometimes they didn't change their clothes for an entire year. The tailors or seamstresses would literally stitch new clothes onto people around Easter-time and that was it for the year. They kept their windows closed because they thought that disease traveled through the air ― something they called "bad ether."

Needless to say, when any new disease arrived in Europe, the unsanitary conditions helped it spread. And so it happened with the "Black Death" ― a bacteria carried by flea-ridden rats.

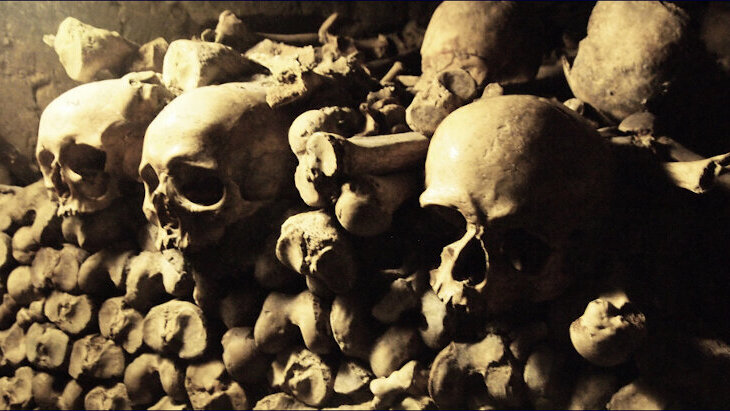

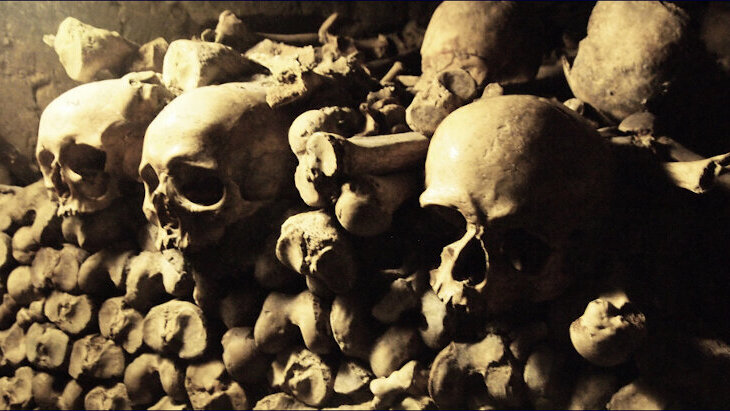

The bubonic plague is estimated to have killed up to half the population of Europe ― about 25 million people.

Although they didn't know what caused the disease, the Europeans had no trouble figuring it out ― it had to be the Jews! The Jews must be getting poison from the devil and pouring it down the wells of Christians (or throwing it into the air) to kill them all off.

To be fair, the Church, specifically Pope Clemement VI, said this was not so, but the masses didn't hear it. The Church's message that the Jews killed "god" but meant no harm to the Christian world just didn't add up.

During the time of the bubonic plague (chiefly 1348-1349), you had massacres of Jews in various European communities. For example, Jews of Strasbourg were burned alive. The collection of documents of Jewish history, Scattered Among the Nations (edited by Alexis Rubin) contains this account:

On Saturday that was St. Valentine's Day, they burnt the Jews on a wooden platform in their cemetery. There were about 2,000 of them. Those who wanted to baptize themselves were spared. Many small children were taken out of the fire and baptized against the will of their fathers and mothers. Everything that was owed to the Jews was cancelled...

(Note in particular the last sentence above.)

In Basle, Switzerland in January of 1349, the entire Jewish community, several hundred Jews, were all burnt alive in a wooden house specially constructed for the purpose on a Island in the Rhine.(1)

When we look at these ridiculous accusations against the Jews, we have to keep in mind that they are not limited to the Dark Ages. The ignorant superstitious masses of Medieval Europe were not the only ones to believe such things. We see this phenomenon in every age including modern history.

For example, an aid to the Mayor of Chicago said in 1990 that the reason why the black community has such high instances of AIDS was because Jewish doctors deliberately put it in their blood supply. The Palestinian Authority has said the same thing several times. The PA has made other outrageous accusations against Israel such as the Israeli Government puts hormones in all the wheat sold to Gaza to turn all Arab women into prostitutes and poisons the chewing gum sold to Arab children. In front of Hilary Clinton, Yassir Arafat's wife said that Jews were poisoning the Palestinian water supply.

Professor Michael Curtis of Rutgers University summed it up perfectly: "Anything and everything is a reason to hate the Jew. Whatever you hate, the Jew is that."

Ghetto

Needless to say, when you think a people are capable of poisoning your wells, you do not want them anywhere near you.

Indeed, as part of the general physical and economic isolation of the Jews throughout the 11th to the 16th centuries (which we covered in Part 46), there were created special areas for Jews to live. These were called "ghettos" ― a name of Italian origin. The Italian word ghetto means "foundry" or "ironworks," and refers to a place where metal was smelted ― a really disgusting smelly part of town, full of smoke and polluted water. In other words, the perfect place for undesirable people.

Although the term ghetto as a place for the Jews was first used in Venice in 1516, the herding of Jews into areas specifically designated for them began several hundred years earlier.

These areas were usually fenced off by a moat or a hedge to designate its boundaries. Jews were allowed outside during the day hours, but at night they had to stay in. A good example is the decree of King John I of Castile (in Spain) in 1412 ordering both Jews and Moslems into a ghetto:

In the first place from now on all Jews and Jewesses, Moors and Moorish women of My Kingdom and dominions shall be and live apart from the Christian men and women in a section or part of the city or village....It shall be surrounded by a wall and have but one gate through which one could enter it. (2)

The ghetto was a mixed blessing for the Jews. While they were kept apart from the rest of society, which was humiliating, they were also kept together. Living together helped them to preserve a sense of community and, since there was no socializing with non-Jews, it was also a guard against assimilation.

The worst part of living in the ghetto was that whenever the masses got it in their heads to kill the Jews ― as they often did around Easter time ― they knew exactly where to find them.

The Christians always offered the Jews a way out of the ghetto ― through conversion to Christianity.

Nachmanides

It was during one of these efforts to get the Jews to convert to Christianity that the great Kabbalist and Torah scholar known as Nachmanides came to prominence.

Nachmanides, Rabbi Moses ben Nachman, better known as Ramban (not to be confused with Rambam or Maimonides) was born in Christian Barcelona in 1194. He became the defender of the Jews in the great Disputation of 1263 ― the most famous of the debates in which the Christians attempted to prove to Jews their religion was wrong in order to get them to convert.

Jews tried to avoid these debates like the plague. Every debate was a no-win situation as Jews were not allowed to make Christianity look bad in any way ― in other words, Jews were not allowed to win.

In 1263, a debate was staged in front of the Spanish King James I of Aragon, and Nachmanides was given the royal permission to speak without fear of retribution. Nachmanides took full advantage of this and didn't mince any words.

His primary opponent was a Jew who had converted to Christianity named Pablo Christiani (a name he adopted after his conversion). As we will see later in history, there were no bigger anti-Semites than those Jews who were trying to out-Christian the Christians. In fact, it was Pablo's idea to challenge the great scholar to this debate, which is a little bit like a high school physics student- challenging Einstein. Realizing that Pablo might need some help, the Church sent the generals of the Dominican and Franciscan orders as his advisors. But even they couldn't stand up to Nachmanides.

The debate revolved around three questions:

Nachmanides answered that had the Messiah come the Biblical prophecies of his coming would have been fulfilled. Since the lion wasn't lying down with the lamb and peace did not rule the planet, clearly the Messiah had not come. Indeed, noted Nachmanides, "from the time of Jesus until the present the world has been filled with violence and injustice, and the Christians have shed more blood than other peoples."

As for the divinity of Jesus, Nachmanides said that it was just impossible for any Jew to believe that "the Creator of heaven and earth resorted to the womb of a certain Jewish woman... and was born an infant... and then was betrayed into the hands of his enemies and sentenced to death... The mind of a Jew, or any other person, cannot tolerate this."

At the end of the debate, which was interrupted as the Church scrambled to minimize the damage, the king said, "I have never seen a man support a wrong cause so well," and gave Nachmanides 300 solidos (pieces of gold) and the promise of continued immunity.(3)

Unfortunately, the promise did not hold. The Church ordered Nachmanides to be tried on the charge of blasphemy, and he was forced to leave Spain. In 1267, he arrived in Jerusalem, where there were so few Jews at the time that he could not find ten men for a minyan in order to pray.

Determined to set up a synagogue, he went to Hebron and imported a couple of Jews. His original synagogue was outside the city walls on Mount Zion, though after his death in 1270 it was moved inside. (After the 1967 Six Day War, the synagogue ― which in the meantime had been turned into a dumpsite ― was restored and is a vibrant place of worship today. Incidentally, the Ramban Synagogue is a subterranean synagogue because at the time Muslim law forbid any Jewish place of worship to be taller than any Muslim place of worship, as we saw in Part 42).

Meanwhile, back in Europe, the Church was still trying to undo the damage of Nachmanides' tour de force. The consequences unfortunately were not good for the Jews.

For one, the Church continued its policy of censorship of all Jewish books (especially the Talmud) containing any references perceived to be anti-Christian. If any such books were found ― without the pages ripped out or otherwise obliterated ― they were burned.

For another, Pope Clement IV issued a special document, called a papal bull, titled Turbato Corde, which later became the basis for the Inquisition policy for persecuting "Judaizers" as we shall see in the next installment.

1) See: Barbara Tuchman, The Distant Mirror ― The Calamitous 14th Century, (Alfred A. Knopf, 1978), pp. 112-114.

2) Alexis P. Rubin ed., Scattered Among the Nations ― Documents Affecting Jewish History 49 to 1975, (Jason Aronson Inc., 1995), pp. 57-58.

3) Nachmanides, himself, recorded the entire debate in a work entitled The Disputation at Barcelona. See also: Howard M. Sachar, Farewell Espan ― The World of the Sephardim Remembered, (Alfred A. Knopt, 1994), pp 39-40.