Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

6 min read

The famous U.S. poet fought for Jewish rights and helped spark the Zionist movement.

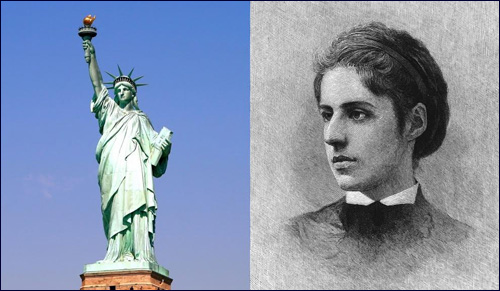

In 1886, France donated a massive gift to the United States: a 305-foot tall statue of a woman holding a torch aloft, symbolizing the shared love of liberty in both nations. But there was one problem: there was no place to display such a towering statue.

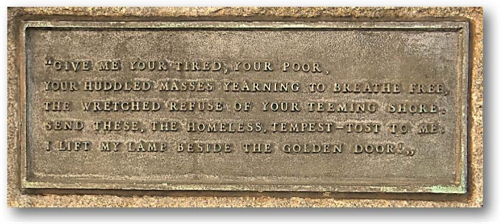

Arts lovers in New York scrambled to raise money to erect a platform for the new statue on Ellis Island in New York Harbor. Hoping to raise publicity and funds, they turned to Emma Lazarus, one of the nation’s best-known poets, beseeching her to write a poem about the statue. Emma initially was resistant, but then gave in, hoping to raise awareness for the plight of poor Jews and other refugees. Her poem The New Colossus, including its iconic plea “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free”, was eventually carved into the base of the Statue of Liberty.

Arts lovers in New York scrambled to raise money to erect a platform for the new statue on Ellis Island in New York Harbor. Hoping to raise publicity and funds, they turned to Emma Lazarus, one of the nation’s best-known poets, beseeching her to write a poem about the statue. Emma initially was resistant, but then gave in, hoping to raise awareness for the plight of poor Jews and other refugees. Her poem The New Colossus, including its iconic plea “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free”, was eventually carved into the base of the Statue of Liberty.

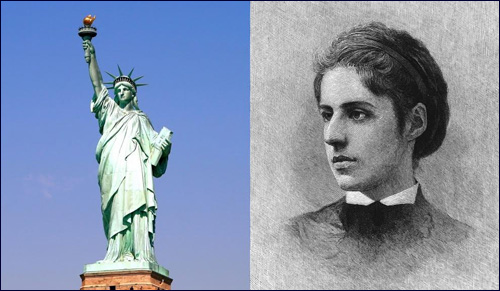

Emma Lazarus started off life with little formal connection to the Jewish community. Born in 1849 into an assimilated Jewish family, Emma’s parents Moses and Esther traced their lineage back to some of America’s earliest Sephardi Jewish settlers from Spain and Portugal, but the family wasn’t particularly observant. Moses Lazarus was a successful sugar trader and the family lived in a comfortable house near New York’s Union Square Park. Emma grew up with a sound classical education, fluent in French and German. Most of her friends were Christian.

Nevertheless, Emma was intensely proud of her noble Jewish ancestors and often wrote about the Jewish rabbis and poets in Spain’s Golden Age, before the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492. As a child, Emma showed early promise as a poet and her father encouraged her, publishing her first book of poems and encouraging Emma to meet and correspond with America’s leading literary figures. She became a fixture in New York literary society and travelled extensively in Europe, counting Ralph Waldo Emerson, Robert Browning, Henry James and William Morris as friends. She once wrote home that she was “drinking in with every sense the spirit...and the beauty of life.”

Though she lived largely in non-Jewish society, Emma was aware that she was sometimes the target of anti-Semitic comments behind her back. “I am perfectly conscious that this contempt and hatred underlies the general tone of the community towards us, and yet when I even remotely hint at the fact that we are not a favorite people I am accused of stirring up strife and setting barriers….” she wrote to her friend and literary journalist Philip Cowen in 1883.

Though she lived largely in non-Jewish society, Emma was aware that she was sometimes the target of anti-Semitic comments behind her back. “I am perfectly conscious that this contempt and hatred underlies the general tone of the community towards us, and yet when I even remotely hint at the fact that we are not a favorite people I am accused of stirring up strife and setting barriers….” she wrote to her friend and literary journalist Philip Cowen in 1883.

A series of bloody pogroms in Eastern Europe in the 1880s sent Jews scrambling to find refuge in America. Between 1881 and 1898 over half a million Jews moved to the United States. These immigrants were as different from the refined, assimilated Jewish community of Emma Lazarus’ youth as could be. They were for the most part Ashkenazi, were more religiously observant, and had fled with very few possessions. As New York’s Jewish population grew, so did anti-Semitism. Emma was appalled at the hostility shown to her co-religionists and began to advocate for them, defying expectations of how a refined young lady should behave.

Emma had previously translated poems by the great German Jewish poet Heinrich Heine, and now she began to identify with his brand of political activism, wielding her pen as a weapon for truth. Though Heine hadn’t been religiously observant, Emma wrote, “he was none the less eager to proclaim himself an enthusiast for the rights of the Jews…” Increasingly, so was she.

Emma translated German translations of medieval Hebrew poetry, bringing these beautiful Jewish works to an American audience for the first time. In 1882 she published a book, Songs of a Semite, that dealt with Jewish themes. Later that year she wrote a play about Jewish persecution in medieval Germany. Emma wrote an impassioned essay about Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s celebrated poem The Jewish Cemetery at Newport, taking strong exception to Longfellow’s final line, “dead nations never rise again”. Nonsense, wrote Emma Lazarus, the many Jews coming to America “prove them to be very warmly and thoroughly alive”.

Emma volunteered with the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society and helped found the Hebrew Technical Institute to teach impoverished Jews job skills.

That life was increasingly visible to Emma Lazarus as she got to know the new Jewish immigrants in New York. She visited impoverished neighborhoods, volunteered with the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, and helped found the Hebrew Technical Institute to teach impoverished Jews job skills. “What would my society friends say if they saw me here?” Emma sometimes joked.

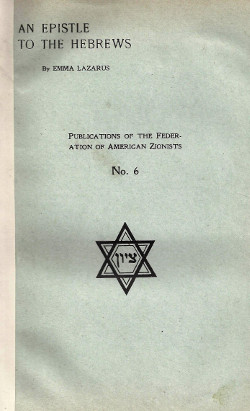

Emma began to call for a Jewish homeland in Israel. In 1882, 15 years before the first Zionist Congress in Zurich, she penned a series of open letters in the journal American Hebrew, called “Epistle to the Hebrews”, calling for American Jews to help establish a Jewish state.

Her series would eventually grow to a set of 15 missives, spanning two years, that eloquently issued a call to action. Explaining to Jewish middle class readers what was happening to their fellow Jews abroad, Emma urged: “We who are prosperous and independent” should feel solidarity with Jews the world over. “Until we are all free, we are none of us free.”

“Until we are all free, we are none of us free.”

At the end of 1882, when she was in the midst of penning her open letters, Emma wrote The New Year (Rosh Hashanah, 5643) that beautifully conveyed her vision of a people “rolling homeward to its ancient source”.

Emma was ahead of her time. She died in 1887 at the age of 38, ten years before Theodore Herzl echoed her call for a Jewish homeland at the Zionist Congress. Twenty years after it first appeared, Emma Lazarus’ “Epistle to the Hebrews” was reprinted by the Zionist Federation of America. American Zionist leader Henrietta Szold credited Emma with helping spark the Zionist movement: “with her own hand she has sown the seeds that shall transform her grave into a garden.”

Emma was ahead of her time. She died in 1887 at the age of 38, ten years before Theodore Herzl echoed her call for a Jewish homeland at the Zionist Congress. Twenty years after it first appeared, Emma Lazarus’ “Epistle to the Hebrews” was reprinted by the Zionist Federation of America. American Zionist leader Henrietta Szold credited Emma with helping spark the Zionist movement: “with her own hand she has sown the seeds that shall transform her grave into a garden.”

Emma Lazarus’ best known poem, The New Colossus, was not displayed in her lifetime. Only in 1903 was it finally engraved on the base of the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor. By then, foes of immigration were calling for fewer Jews in the United States. In 1924, the Johnson-Reed Act severely limited the number of Jews who could find refuge in the United States; only about 200,000 Jews were admitted to the country from 1933 to 1945. Emma Lazarus’ dream of a Jewish refuge went unheeded.

In 1948, however, Emma Lazarus’ dream of a new Jewish homeland came true, with the establishment of the state of Israel, nearly seven decades after she first bravely called for the return of her ancient people to it source.