Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

10 min read

A specific legal process is required to break the marital bond.

Although divorce is common in today’s social landscape – prevailing wisdom says that up to half of all marriages will end in divorce – it is still a heartbreaking way to end a marriage.

Unlike some religions, however, which do not permit divorce, Judaism recognizes the necessity under certain circumstances. Indeed, following the proper procedure for divorce is one of the 613 mitzvahs in the Torah.

What is the method of a Jewish divorce?

Just as marriage is a metaphysical reality – two souls fusing together to create one complete soul – so too divorce is a metaphysical reality. For a Jewish couple to become divorced, the man must give the woman a document called a "Get," as prescribed in the Torah (Deut. 24:1-4). A Get terminates the Jewish marriage and certifies that the couple is now free to remarry according to Jewish law.

Aside from the legal considerations, a Get can provide a sense of emotional closure – just as the marriage began with a Jewish ceremony, it ends with one as well.

Without a proper Get, even though the man and woman have physically separated, they are still metaphysically bound together – and considered as if fully married. This is true to the extent that if a woman were to become “remarried” without having received a proper Get, the second marriage is null and void, and is considered adultery.

A secular divorce does not count for a Get.

The Procedure

A Get must be written in a very specific way, and only under the supervision of an expert rabbi who is well-versed in these laws. For example, the Get must be written specifically for this couple, and a pre-printed document cannot be used. There are other complex factors as well, including the type of people who must witness the giving of the Get, and precise formulas for the spelling of words and names. All of this must be done properly, or else the couple is still considered as if fully married.

A Get must be written in a very specific way, and only under the supervision of an expert rabbi who is well-versed in these laws. For example, the Get must be written specifically for this couple, and a pre-printed document cannot be used. There are other complex factors as well, including the type of people who must witness the giving of the Get, and precise formulas for the spelling of words and names. All of this must be done properly, or else the couple is still considered as if fully married.

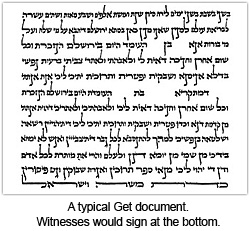

The Get document is written by a trained scribe (sofer). It contains 12 lines of text, written in Aramaic which was the vernacular during Talmudic times. The text states the location, man’s and woman’s names, and a brief pronouncement that the woman is now free to remarry. The man hands the Get to the woman, in the presence of two authorized witnesses. There are no prayers or blessings involved. The entire proceeding normally takes about an hour, and usually takes place in the rabbi's office.

In situations where direct contact between the husband and wife would be difficult (due to either geographic constraints or emotional displeasure), the process can be done via proxy.

The Get document itself remains in the files of the officiating rabbi, and is torn so that it cannot be used again. The rabbi issues a certificate of proof to both parties, attesting to the fact that a Get was properly drawn up, delivered and accepted, and that each party is free to remarry.

A Get can be arranged at any subsequent time, even years later. Nevertheless, from the standpoint of Jewish law and as a practical matter, it should be done as soon as possible.

For assistance in arranging a proper Jewish divorce, go to kayama.org.

Eye to the Future

When getting divorced, a Get is not only the right thing to do, it is the wise thing to do. Regardless of one's personal convictions or beliefs, it solves a lot of problems down the line – ensuring free social interaction within the Jewish community.

A second marriage is not possible without a Get.

For example, someone who is divorced for many years and then wants to remarry, cannot do so without a Get. If it wasn’t take care of the first time, they would now have to track down the "ex," wherever s/he is, and ask for their cooperation in the process of a Get. Imagine the possible heartache and complications. Any responsible rabbi will refuse to officiate at a wedding unless both the man and woman show proof that any prior marriage was properly terminated according to Jewish law.

Furthermore, if the divorce is not performed properly, there is a danger to future generations: If a child is born to a mother who is still technically married to someone else, that child may be considered illegitimate (mamzer). Such a child may be barred from marrying into the broader Jewish community, possibly depriving them of the opportunity to marry the individual of their choice. A very powerful novel, Yesterday's Child, deals with this issue.

As such, attaining a proper Get is an important component of preserving Jewish unity.

When to Get Divorced

Let's take one step back and ask: What is the Jewish understanding of marriage?

The act of marriage is more than just a man and woman sharing a house, or having a joint bank account, or raising children together. Marriage actually binds two souls together to create one complete soul. As the Torah says, a married couple "becomes one flesh" (Genesis 2:24).

“One flesh” means that the commitment of marriage is like the commitment one has to his hand. As one rabbi explained:

What is my commitment to my hand? I "am" my hand! I wouldn't reconsider my commitment to my hand if it were broken, ugly, scarred, or if I met someone with nicer hands. I'd reconsider my commitment to my hand only if it had gangrene and was killing me.

The commitment of marriage is until it's killing you.

The alarming rate of divorce means there is a fundamental problem in how many people approach marriage and relationships. As Rabbi Avram Rothman observes, the media has geared people to become a society of “takers.” "You deserve a break today," "Just do it," and other catchy slogans entice people to take what they want, do what they want, and think only of themselves. If there is one overriding factor causing the many failed and troubled marriages, it is that we have learned to be "takers."

The Jewish idea of marriage is to be a “giver.”

When two people are focused on taking, they are pulling in opposite directions. It’s a constant tug of war to see how much the other person “can satisfy me.” By contrast, the Jewish idea of marriage is to be a “giver.” In this way, the dynamic between husband and wife is a loving, caring flow in both directions. (Interestingly, one way that Jewish law facilitates this is through the Ketubah wedding contract, where the man commits to providing his wife’s needs – food, clothes, intimacy, etc.)

Of course, there are times when marriages fall into a destructive cycle of abuse, and in these situations, divorce is appropriate. Even more, divorce is a mitzvah – a chance to try again, to find happiness.

In reality, however, this is often not why most people get divorced. They usually just get tired of each other. The excitement goes out of the relationship, or "we don't laugh like we used to." If someone told you they were amputating their hand because "the fun has gone out of it," you'd think they were crazy.

It is for this reason that prior to facilitating a Get, a Jewish court (Beit Din) will sometimes encourage the couple to seek reconciliation. In fact, one of the reasons the Jewish divorce process involves so many technicalities is to avoid a situation where people get divorced without having fully explored the options.

Throughout history, Jews have sought an ideal standard for family life that is captured in the term Shalom Bayit – literally, “peace in the home.” When marital harmony exists, God's presence dwells in the home. When marital harmony is absent, and divorce becomes the only option, it is an undeniable tragedy. The Talmud (Sanhedrin 22a) says that when a divorce occurs, the Temple altar – the symbol of Jewish unity and holiness – metaphorically “weeps," as if to mourn the loss of this failed union.

According to the Gaon of Vilna, the Hebrew letters gimmel and tet (spelling “Get”) do not otherwise appear together in any word – symbolizing the disharmony which precipitates divorce.

Recalcitrant Spouse

A Jewish marriage can be terminated only through the death of one spouse, or with divorce. In a case where the spouse is not known to be dead, nor available to give a Get, that would leave the surviving spouse in limbo, unable to become remarried.

This situation is called agunah – the "chained" spouse. This concept appears in the Talmud primarily in connection with a husband who disappeared or was missing in action. (This issue unfortunately became common in the aftermath of the Holocaust.) Even today, a spouse will sometimes withhold a Get out of spite, or in an attempt to extort money or concessions in the areas of child support, custody, or marital property.

The agunah problem commonly refers to a man who is recalcitrant. However, since Jewish divorce requires mutual consent, if a woman refuses to cooperate in receiving a Get, a man could be in this state of limbo as well.

What can be done to prevent this appalling situation?

Various sanctions and pressure have proven effective.

In the State of Israel, if a man was ordered by a Beit Din to give his wife a Get and he refuses, he could be imprisoned until he complies. Other sanctions include the revocation of his driver’s license or passport, depriving him of visitation rights, imposing a monetary fine, and/or denying him participation in synagogue activities. This type of pressure has proved effective.

Other methods of persuasion are perhaps more apocryphal. I have heard of high school students standing outside a man's office carrying placards with his picture and information about what he was doing to his wife. One episode of the TV show The Sopranos featured Tony being hired to convince a stubborn Jewish man to give his wife a Get – or else face dismemberment.

In the State of New York there is a law linking the validity of civil divorce to the proper completion of a religious Get – i.e. a husband is unable to obtain a civil divorce until he removes all impediments to his wife’s ability to remarry. (This has also helped other faith-based communities who may have similar problems.)

The topic of agunah is very detailed with many accompanying controversies. For more information, see this article by Rabbi Yitzchak Breitowitz.

Assistance in resolving a specific case of agunah is available at getora.com.

A Word About Children

In the 1970s, Judith Wallerstein’s best-seller The Unexpected Legacy of Divorce contended that children really aren't as “resilient" as once thought, and that divorce can present children with a lifetime of emotional struggle. Here are three cardinal rules for making divorce less stressful for children, and reducing the chances of long-term trauma:

An excellent book on this topic is M. Gary Neuman’s Helping Your Kids Cope with Divorce the Sandcastles Way. Over 20,000 children have taken part in the half-day Sandcastles workshop, which is now mandatory in certain regions of the United States.