Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

16 min read

Eighty years ago, an Arab mob went on a rampage and murdered 69 Jews.

On August 23, 1929, the day before the Hebron Massacre, rumors were circulating about anticipated riots, but of the 700 Jews who lived in Hebron, most did not believe anything bad would happen to them. They considered their relations with their Arab neighbors to be strong, based upon years of friendship and shared experiences. Moreover, the Arab Governor of Hebron, Abdullah Kardos, had promised the Jews that they would not be harmed.

According to first-hand accounts recorded in Sefer Hevron, [1] the most comprehensive book on the history of Hebron, some Jewish notables in the city, among them Eliezer Dan Slonim, the highly respected manager of the Hebron branch of the Anglo-Palestine Bank and the son of Rabbi Yaakov Yosef Slonim, the chief Ashkenazi rabbi of Hebron, met to discuss the situation. When they couldn’t resolve their differences of opinion, they went to consult with Rav Meir Franco, the chief Sephardi rabbi of Hebron. Together they decided to bring the Jews who were scattered in outlying areas to homes in the city center, where they thought it would be safer.

As they walked out of the meeting, they were met with a barrage of stones thrown by Arab youths. Yet, shortly after the Arabs finished their Friday prayers, Arab notables came to Slonim to reassure him that no harm would come to the Jews of Hebron.

These notables were either misinformed or misinforming. At 2:30 that Friday afternoon, a young Arab on a bicycle, coming from Jerusalem, called out to the Arabs of Hebron that the Jews were murdering thousands of Arabs in Jerusalem. Other Arabs in cars followed him, shouting that Jews were attacking Arabs (rather than vice versa, as it was in reality).

The riots were hardly spontaneous.

According to The Martyrs of Hebron, which was written by Leo Gottesman, who was a student at the Slabodka yeshivah but was not present at the time of the massacre, [2] the author’s brother was on his way back to Hebron for Shabbat in a cab filled with Arabs, when he saw them eyeing him and snickering. He realized that something was afoot; when his hat blew out an open window, he used it as an excuse to leave the cab and escape back to Jerusalem.

The riots were hardly spontaneous. The mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini, (who would, in the ensuing years, offer help to Hitler) had been preaching venomously against the Jews. In 1924 the Moslem Wakf began the instigating against the Jews’ connection to the Kotel, and in 1928, the mufti further provoked a dispute about the Kotel, claiming that the Jews were trying to take control of the mosques on the Temple Mount. The Moslems argued that the Kotel was holy to them because Mohammed had tied his horse there before he went up to the Temple Mount. (To this [3]day, in fact, the Moslems call the pogroms of 1929, “the pogroms of the horse.”) On erev Tishah B’Av 1929, a week before the Hebron Massacre, a large demonstration was held by the Jews, in the plaza before the Kotel, in an attempt to affirm the Jewish connection to the Kotel.

The riots were hardly spontaneous. The mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini, (who would, in the ensuing years, offer help to Hitler) had been preaching venomously against the Jews. In 1924 the Moslem Wakf began the instigating against the Jews’ connection to the Kotel, and in 1928, the mufti further provoked a dispute about the Kotel, claiming that the Jews were trying to take control of the mosques on the Temple Mount. The Moslems argued that the Kotel was holy to them because Mohammed had tied his horse there before he went up to the Temple Mount. (To this [3]day, in fact, the Moslems call the pogroms of 1929, “the pogroms of the horse.”) On erev Tishah B’Av 1929, a week before the Hebron Massacre, a large demonstration was held by the Jews, in the plaza before the Kotel, in an attempt to affirm the Jewish connection to the Kotel.

In the aftermath of the demonstration, the mufti encouraged riots around the country. To what extent he merely “encouraged” them and to what extent he actually orchestrated them is still a matter for research, according to Aryeh Klein. “I believe he orchestrated them,” says Klein, “but it is difficult to prove.” Since the British were blatantly pro-Arab, he was able to stir them up unhindered. In Motza, for example, a suburb of Jerusalem, there was the cruel murder of the Makleff family. There were murdered the day before the Hebron Massacre. One of the three children who survived -- Mordechai Makleff -- became the fourth chief of staff of the IDF.

Hebron Jews were particularly vulnerable since they had made the city more modern and economically prosperous. While the Arabs who wanted modernity regarded the Jewish presence as a blessing, those who didn’t, despised the Jews and led the incitement. [4]

An angry Arab mob gathered at the home of the deputy police commander of Hebron and took to the streets. At the same time, the elderly Rav Slonim was on his way to [Captain Cafferata,] the [British] police commander of Hebron. He was attacked and beaten by the mob. Another British police commander, who stood behind the mob, was approached by a Jewish woman and asked to intervene. “It’s usually the Jews who are to blame in these things,” he said, stirring up the Arab crowd even more. [5] Rav Slonim turned to an Arab police commander for help, who shoved him away with his horse.

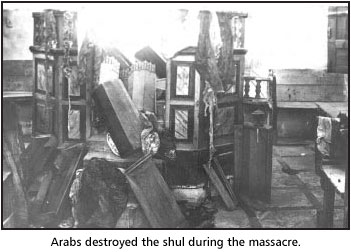

It was almost Shabbat. Some Arabs broke into Hebron’s Slabodka yeshivah [6] which was, mercifully, almost empty, as of the 150 students, many were either on summer vacation or were preparing for Shabbat. [7] The mob murdered the one student they found there -- Shmuel Rosenholtz, a conscientious, young yeshivah student who had prepared for Shabbat early and came to the yeshivah to review the Torah portion. As the Arabs made their way back through the streets, an Arab who had participated in the murder of Rosenholtz boasted, “Too bad, we went to the yeshivah and found only one boy. Tomorrow the number will be higher.” [8]

The morning hours brought bloody and brutal horror.

A terrified quiet ensued. The morning hours brought bloody and brutal horror. Frenzied Arab mobs with axes, knives and iron bars, screamed “Kill the Jews!” They broke into homes and stabbed and mutilated the Jews they found. The mob that rampaged through the city included respected Arab merchants and “good” neighbors who killed their friends, clients and business associates. Torah scrolls were burned. The Hadassah building, [9] where Arabs were treated free of charge, was broken into, and all the medical equipment and the pharmaceutical supplies were destroyed.

A video database of survivor testimonies appears on the web site of the present-day Hebron community (www.hebron.com). The testimonies (in Hebrew) were compiled by David Wilder, the site’s creator. The following is from that collection: [10]

Rachel Graziani: On that same black Shabbat, when Ima took out the cholent, we heard screams, and we looked through the window and saw a mad mob of Arabs, and father moved us away from the window and pushed something against the door. They didn’t succeed in getting through the door, and then--with the belief that they were friends and would do nothing to us -- he said, “I’ll open the door if you take anything you want and don’t hurt anyone.” And he opened it. They pulled him outside, and leading the mob was his “friend” from work.... [Later] when the British took us away, I saw my father downstairs, murdered. I will not forget that.

I remember my mother [holding] my brother, only a few months old, and an Arab tried to stab her, and my mother said, “Are you not afraid of God? He won’t forget that you are going to kill a woman and a boy,” and he left her. My grandmother, who someone tried to rape--she was beautiful, but she was also strong-- also said, “Aren’t you afraid of God?” and he left her alone. It was a horrifying scene. We went up to the roof and hid there. We heard the screams; we heard everything; we were like terrified rabbits, hiding...

The mob went from house to house. The British and Arab policemen stood by, watching the slaughter. Some of the Arab policemen even spurred the rioters on [11] or participated in the riots. [12]

In the home of Eliezer Dan Slonim alone, where many people had gathered, thinking they would be safe there, 22 men -- still wrapped in their prayer shawls --women and children were slaughtered, including Eliezer Dan himself, his wife, Hannah, one of their children and Hannah’s parents. Hannah’s sister and a yeshivah student were miraculously saved because he shoved her into a closet, and held her mouth closed so she wouldn’t scream when she saw, through the crack, her parents being murdered.

In the home of Eliezer Dan Slonim alone, where many people had gathered, thinking they would be safe there, 22 men -- still wrapped in their prayer shawls --women and children were slaughtered, including Eliezer Dan himself, his wife, Hannah, one of their children and Hannah’s parents. Hannah’s sister and a yeshivah student were miraculously saved because he shoved her into a closet, and held her mouth closed so she wouldn’t scream when she saw, through the crack, her parents being murdered.

Many sought refuge with Slonim since he was known to have good connections with both the British and the Arabs; but the mob was specifically looking to murder the rich and the connected. [13] In the home of Gershon Ben-Zion, the Hebron pharmacist, the mob gouged out his eyes and stabbed him over and over again; they cut off the hands of his wife and fatally wounded her. They also tried to torture his daughter, but she resisted with all her might and they murdered her “in a strange and cruel way.” [14]

Through the hills of Hebron, the screams of the tortured and maimed Jews, mixed with the shrieks of the satanic mob, “howling like wild animals over their prey.” [15]

Abu Shaker told the marauders that they would pass through that door to murder the Jews over his dead body.

There were also stories of Arabs who risked their own lives to save Jews. Rivka Slonim Burg -- the daughter of Rav Slonim and the sister of Eliezer Dan Slonim – recalls [16] that before the massacre there were good relations with the Arabs in the area. “We were even invited to each other’s semachot, joyous occasions.” She was only eight years old when, together with the rest of her immediate family, she hid behind Abu Shaker, the Arab neighbor who stood in the doorway of her family’s home in Hebron, protecting them from the mob. Rav Slonim and his family lived in a two-family house, and Abu Shaker was their landlord. “When our landlord heard that something was happening in the city, he came and stood in the entrance to the house,” recalls Rivka. Abu Shaker told the marauders that they would pass through that door to murder the Jews over his dead body. “We heard what he said [to the mob] while he stood at the entrance. They [the Arab mobs] wounded him but they didn’t go into the house.”

“After the massacre, the British took everyone to the police station. But my father, a rav, would not ride there on Shabbat,” said Rivka. “So we went on foot, and we saw bodies, pieces of limbs and blood along the way.”

Rav Slonim died in 1937, in mourning for family and his community that had died in the massacre. Letters reprinted in Sefer Hevron reveal, however, that after the massacre, Rav Slonim persisted in trying to restore the Jewish presence in Hebron. There was an official committee formed to help the Jews return to Hebron, Havaad L’Ezra L’Plitim -- The Committee to Help Refugees -- but they didn’t really facilitate the returning. Nevertheless, there were Jews who returned in 1931.

Rivka, who spent the rest of her childhood in Jerusalem, later married the late minister Yosef Burg of the National Religious Party (Mizrachi). Right after the Six Day War, she returned, with her husband, to visit Hebron. There she looked for the family that had saved her. “All the [original] residents of the city ran away during the Six Day War because they were afraid that the Jews would take revenge, but we found one of the sons of Abu Shaker, who had stayed to watch over the family’s possessions,” says Rivka. He has since died. “We -- my husband, my sister and I -- all stood around him. Suddenly, he asked, ‘Where is Rivkale?’ He was very emotional.”

“Not very much is left from my Hebron,” Rivka says. “The Arabs destroyed the home of my married brother, Eliezer Dan Slonim. My school had also been in that area. The Arabs built a shopping area there.”

The Aftermath

When the mob was through, there were 69 dead and scores wounded, more than 20 of the dead were yeshivah students. The surviving Jews were taken to the police headquarters -- located in Beit Romano, which today houses Yeshivat Shavei Hevron -- and from there, the wounded and dead were removed to the government health ministry building. According to Sefer Hevron, the survivors remained for two days under the eyes of the British, without food, lying in blood and filth, in deepest shock, until they were finally able to pull themselves together enough to go buy pitot.

Survivors remained for two days under the eyes of the British, without food, lying in blood and filth.

The Arab doctors in the government health ministry building were not interested in helping the wounded. Thirty-six hours after the massacre, a British surgeon with an assistant and two nurses came from Jerusalem to take care of the scores of wounded. Eventually the survivors were taken to Hadassah Hospital, then on Straus Street, in Jerusalem, where they were met by hundreds of anguished Jews who came to comfort them and mourn with them. [17]

On Sunday evening the Jews wanted to start burying their dead in Hebron. There were five long graves dug out, called Kever Achim (Tomb of the Brothers). The bodies were placed in order in these graves, and in the last one were placed unidentified body parts. (footnote to Sefer Hevron page 417) According to David Wilder, Hebron spokesperson for the foreign press, “All the bodies were identified and laid out in order and recorded and there were markers in order. The markers there today are as they were in 1929.” (Footnote to phone interview with David Wilder, April 23. 2004.)

At some point between 1948 and 1967, when Hebron was under Jordanian rule, Arabs dug up the gravesite and used it as a vegetable garden. After the Six Day War, the Israelis rebuilt the cemetery and reconstructed the gravestones.

One week after the massacre, 24 Jews were murdered in Tzefat, before the British intervened. The Arabs began to burn the Tzefat Jewish Quarter but the Jews of Tzefat were stronger and more organized than those in Hebron, and when the British brought trucks to take them away, as they had done with the Jews of Hebron, the Tzefat Jews insisted on staying in their burnt homes.

After the massacre, which came to be known as “Meoraot Tarpat --The Events of 5689,” Rav Franco and Rav Slonim made a list of those Arabs who saved Jews during the massacre. The list is published, along with other documents, in Sefer Hevron. Out of a community of 18,000 Arabs, there are nineteen names on the list. Sefer Hevron includes the summation of the protocol from the trials, which note that only five Arabs were brought to trial. The two judges were an Englishman and an Arab. The prosecutor was Arab, a relative of the Jerusalem mufti. Sheikh Talab Maraka, the leader of the murderous mobs, was given a two-year jail sentence but sat in jail only one month. The British used various legal tricks in order to bring as few murderers as possible to trial, but three Arabs were hung in Hebron. These Arabs are considered national heroes by the Palestinians, and during the first intifada, which commenced in 1987, Arabs throughout Judea and Samaria held a strike day in their memory, and they held a special memorial for them in Hebron.[18]

The British censored all newspapers and did not allow anything to be printed about the events of Tarpat, officially because it “would encourage other pogroms.” However, in an ironic twist, pamphlets and books were not censored, so newspapers circumvented the censorship by producing special pamphlets, such as “Davar Hayamim Haelah” -- “The Word on These Days,” [19] published by Davar.

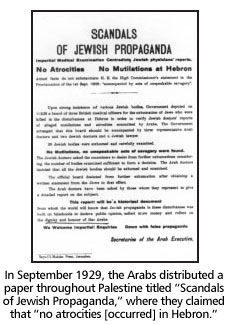

In September, 1929, the Secretaries of the Arab Executive distributed a paper throughout Palestine and the world titled “Scandals of Jewish Propaganda,” which stated that “no mutilations” and “no atrocities at Hebron” occurred. It also accused the Jews of publishing lies about the Arabs of Hebron to “deceive public opinion, collect more money and reflect [negatively] on the dignity and honor of the Arabs.”

In September, 1929, the Secretaries of the Arab Executive distributed a paper throughout Palestine and the world titled “Scandals of Jewish Propaganda,” which stated that “no mutilations” and “no atrocities at Hebron” occurred. It also accused the Jews of publishing lies about the Arabs of Hebron to “deceive public opinion, collect more money and reflect [negatively] on the dignity and honor of the Arabs.”

The Hebron massacre was a landmark in the history of the yishuv. Before 1929, the yishuvthought that the British would protect the Jews. After the massacre, the Jews understood that they would have to take care of themselves, and the Haganah, which had been a small organization, began for the first time to fulfill a military function.[20]

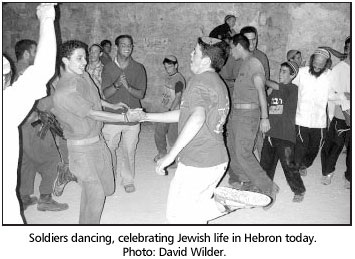

The sounds of Torah and Jewish life ring out again in Hebron.

Today there is a small museum in Hebron commemorating the events of Tarpat. It was donated by Rebbetzin Gitl Rosensweig of Toronto in the early ‘90’s, in memory of her husband, Rabbi Feivel Rosensweig. In a cruel twist of irony, Gitl’s son-in-law, David Rosenzweig was murdered on July 14, 2002, in Toronto, by skinheads.

Whither Now?

From 1948 onward the Jews from Hebron maintained a public association – Vaad Kehilat Yehudei Hevron - the committee for the kehila of the Jews of Hebron. Judge Moshe Hason, who had been a resident of Hebron, was the head of the committee that continued to function into the 1950's and beyond. After the Six Day War in 1967, during which Hebron came into Israel's hands, they went to the Israeli government to try to have their property in Hebron returned to them, but nothing came of it.

On Passover, 1968, Jews returned to resettle the area. Kiryat Arba was built on the adjoining hill in 1971. In 1979, Jews moved back into Hebron proper, where the massacre had occurred. Today the Jewish community in that area lives in homes that were public Jewish property, or in new homes built on grounds that were public Jewish property - homes that were owned by the kehila, the community, at the time of the massacre. This included the entire Jewish quarter. Chabad was the only exception; it is considered "public" even though it was originally private, because it is owned by the Shneerson family but the Rebbe handed it over for the use of the Jewish settlement in Hebron. There are Jews living in Beit Shneerson today.

On Passover, 1968, Jews returned to resettle the area. Kiryat Arba was built on the adjoining hill in 1971. In 1979, Jews moved back into Hebron proper, where the massacre had occurred. Today the Jewish community in that area lives in homes that were public Jewish property, or in new homes built on grounds that were public Jewish property - homes that were owned by the kehila, the community, at the time of the massacre. This included the entire Jewish quarter. Chabad was the only exception; it is considered "public" even though it was originally private, because it is owned by the Shneerson family but the Rebbe handed it over for the use of the Jewish settlement in Hebron. There are Jews living in Beit Shneerson today.

Three Hundred yeshivah students study in Yeshivat Shavei Hevron, in Beit Romano, where the survivors of the Hebron massacre had once gathered.

A longer version of this article originally appeared in Jewish Action, the magazine of the OU, Summer, 2004 edition.