An Open Letter to University Presidents

An Open Letter to University Presidents

9 min read

Ishmael Khaldi tells Aish.com what it's really like being a minority in Israel.

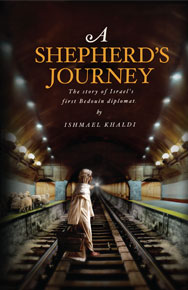

It was after Ishmael Khaldi, 39, visited the University of California, Berkeley campus as Israel’s Deputy Consul General to the U.S. Pacific Northwest in 2006 that he decided he needed to write a book. “People at Berkeley didn’t want to shake my hand because I was there representing Israel,” says Khaldi, author of the recently-released A Shepherd’s Journey, a biographical account of growing up as a minority in Israel. “This encounter, with such ignorance, deep criticism, and inflammatory rhetoric, was the most shocking moment of my career so far.”

Khaldi believes that much of the Western world – the Jewish community included – have a skewed and inaccurate picture of what Israel is all about.

Khaldi’s hope is that his book will help shed a little light on the subject, and provide an inside view of the country’s Muslim Arab minority. “Although Israel is part of Jewish identity and connects every Jew around the world, the state of Israel is not just Jewish and Zionist. It’s a country of all its citizens,” says Khaldi. “My very existence proves that Israel is one of the most culturally diverse societies and the only true democracy in the Middle East.”

The first Israeli diplomat of Bedouin descent, Khaldi grew up as a shepherd in a tent in a traditional Bedouin village.

The first Israeli diplomat of Bedouin descent, Khaldi grew up like most of Israel’s 180,000 Bedouin, as a shepherd in a tent in a traditional Bedouin village. He walked four miles round trip to school each day from his village of Khawalid, near the Jewish town of Kiryat Ata, in the Haifa region. Like most of Israeli’s northern Bedouin, his village established close ties with neighboring kibbutzim, and since the 1930s has had amicable relations with Jewish Israelis, who have played a big role in helping to advance Bedouin technological and agricultural production. Khaldi’s grandmother even learned to speak Yiddish!

Unlike most Bedouin, however, Khaldi, decided not to build a modest home nearby his parents and start his own family and herd. Instead, when he finished his national IDF service (a service both he and all of his brothers completed), he went off to see America. On his return, he earned a degree in Political Science at the University of Haifa, then an M.A. in Political Science and International Relations at Tel Aviv University. After this, he began working for the American embassy in Tel Aviv, then Israel’s Foreign Service, a move which landed him the job at the Israeli Consulate in San Francisco, and onto the Berkley campus.

Apartheid State?

Khaldi’s entire adventure – from tending goats on the hills of northern Israel to meeting North American volunteers from the neighboring Kibbutz Kfar Hamaccabi, to his first foray in New York, where he unknowingly runs across the subway tracks to get to the right side and is eventually “rescued” by a Haredi family in Borough Park, to his long-distance romance with a Bedouin girl from a village next to his family’s, to his formation of close friendships with secular and religious Jews and Muslims on two continents, and finally to his ascent to the Israeli Foreign Service – is recorded in his intriguing new book.

Khaldi’s entire adventure – from tending goats on the hills of northern Israel to meeting North American volunteers from the neighboring Kibbutz Kfar Hamaccabi, to his first foray in New York, where he unknowingly runs across the subway tracks to get to the right side and is eventually “rescued” by a Haredi family in Borough Park, to his long-distance romance with a Bedouin girl from a village next to his family’s, to his formation of close friendships with secular and religious Jews and Muslims on two continents, and finally to his ascent to the Israeli Foreign Service – is recorded in his intriguing new book.

Khaldi attributes his own uncommon life trajectory to the opportunities available to minorities in Israel. “Israel is a multi-cultural, multi-lingual, multi-religious society,” says Khaldi, referring to the religious freedoms, women’s rights, equal educational opportunities, economic development, freedom of the press, and legislative representation. “Israel can be an example to the region and help facilitate the creation of regional wealth and development.”

Of course, Israel is not perfect. There is some level of bureaucratic discrimination and an unequal allocation of resources, both on ethnic and non-ethnic bases. But, says Khaldi, the situation of minorities in Israel is no different from the situation of minorities in the United States and other Western democracies.

“There are African American diplomats representing the United States – now there is an African American president – but that doesn’t mean discrimination does not exist in America,” says Khaldi. “It also doesn’t mean that, because there is discrimination, African Americans should wash their hands of their country of birth.”

Furthermore, says Khaldi, given that the U.S. is 234 years old, and Israel is a mere 62 (plagued by external threats, massive immigration, and internal tumult), the status of minorities in Israel is way ahead of the curve, particularly compared with the treatment of minorities in neighboring Arab countries.

“Israel may be the only country in the Middle East where a Bedouin shepherd can become a high-tech engineer, a scientist or a diplomat. The sky’s the limit.”

Khaldi says that he is living proof that Israel is not the "Apartheid state" that some make it out to be. “Israel may be the only country in the Middle East, if not the world, where a Bedouin shepherd can become a high-tech engineer, a scientist or – a diplomat. The sky’s the limit.”

Arab-Israeli Integration

Admittedly, most members of Israeli minorities don’t make it as far as Khaldi. But he says this has less to do with the opportunities offered by the country than with a resistance to integrate; what Khaldi dubs “a self-imposed barrier to full integration into a modern life.”

Most Bedouin struggle between a desire to embrace modernity and at the same time preserve their heritage and customs. Khaldi is no exception. “In a lot of ways I am stuck between worlds,” he says. “We are a very traditional and conservative people, and it is difficult for us to integrate, particularly into modern, secular, liberal mainstream Israeli society.”

Interestingly, it is for this reason that Khaldi says he feels most comfortable in the company of religious Jews, whose culture and values tend to be much more conservative.

Khaldi recalls when he first landed at JFK International Airport, where he was shocked to be met by such a chaotic mix of people and graffiti, and cars and jet engines. “All at once, my exhaustion and anxiety broke open. I felt like the world was collapsing around me, and I cried like an orphan newborn lamb whose mother had just died,” he writes.

Then suddenly, like a bolt of lightning, he spotted a Hassid in the terminal, on the floor above him. “My heart swelled and my mood brightened immediately. I felt as if I had been lost at sea and suddenly spotted a beacon of light,” he writes. It was that Hassid that pointed him in the direction of Borough Park, Brooklyn, where he quickly found refuge with another Hassidic family.

Lost in New York, Khaldi found refuge with a Hassidic family in Borough Park.

Khaldi is confident that the resistance among Israel’s minorities to integrate will melt away with time. Already, the young Bedouin generation is much more integrated and modern than the one before. The same can be said for other Muslim minorities in Israel, although in general the level of resistance among other Arab Israelis is fiercer than among the Bedouin.

Unlike the Bedouin, who are by and large loyal to Israel, many other Arab Israelis are more politically-minded and align themselves with the Palestinians and their national aspirations. What accounts for the difference?

Khaldi explains that Bedouin, who by legend are said to be born of the wind due to their nomadic nature, don’t feel strong ties to any land in particular and never have; whereas the fellahin (Arab ‘farmers’) are agricultural and territorial by nature.

Khaldi came to understand this difference when he went to grade school in the nearby fellahin village of Ras Ali, and again in high school at the Haifa Arab Orthodox College, where he was chastised for his loyalty to Israel.

“I always thought I was an Arab, until I went to school with Arabs who told me no, that I was Israeli and Bedouin. Whereas we [Bedouin] consider ourselves Israeli first and Arab second, they consider themselves Arabs who happen to live in Israel,” he says.

One of his most bitter memories is of his first Memorial Day at the Haifa Arab Orthodox College, where he drew a great deal of attention to himself standing outside his class to observe the moment of silence. “This outraged my fellow students, who taunted, ‘The Bedouins standing with Israel are traitors,’” recalls Khaldi, whose brothers Hamudi and Amin were doing their service with the IDF at the time. “I felt miserable, but I stood there all the same. I am, after all, a proud Bedouin.”

He encountered the same sort of segregation from members of other Muslim communities. “Although I am an Arab Muslim, I am often greeted with suspicion by other Arab Muslims. They look at me first of all as Israeli,” says Khaldi, who now works as a political advisor to Foreign Affairs Minister Avigdor Lieberman.

Yet things are changing. Khaldi says that at least among Israeli Arab fellahin, the sentiment is beginning to wane and that like Bedouin, Israeli Arabs are starting to integrate.

“The world is changing. The younger generation is much more exposed to other values and other cultures and the differences between them are disappearing,” he says. Khaldi points to the growing number of Arab high school girls participating in national service (Sherut Leumi).

This is just one example of many that Khaldi says fills him with hope for the future of Israel and its minority populations. “I am a proud third-generation Israeli. And while it will continue to be a challenge to preserve our culture, I look forward to raising a young generation that is even more Israeli than me,” he says. “There are differences in tradition and religion between us, but at the end of the day we are all Israeli citizens.”

A Shepherd’s Journey is available both on Amazon.com and at www.Ishmaelkhaldi.com.

A Shepherd’s Journey is available both on Amazon.com and at www.Ishmaelkhaldi.com.