Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

3 min read

4 min read

4 min read

12 min read

Fortunately they were able to painstakingly put the pieces of their lives back together.

According to a 2011 report, only 16% of the families who continued in the community frameworks in which they had lived in Gush Katif had completed building and moved to a permanent home. There were some who could not tolerate the feeling of impermanence and who therefore left their "home" communities to set up house independently in various cities and towns. Only 28% of growers had resumed farming, and 20% of former Gush Katif residents remained unemployed. Hopefully, these statistics have improved somewhat in the last year.

The stories I’m going to share with you are not about the unemployed, or about those whose marriages sadly disintegrated, or about the children who developed serious school, social or personal problems,. It is about my own immediate and extended family about whom I wrote seven years ago. Thank God, they are among those who were able to painstakingly put the pieces of their lives back together.

Ruti and Hezi Cohen of Ganei Tal

In 1999, our daughter, Na'ama, married Avner Cohen, son of Ruti and Hezi Cohen of Ganei Tal. It was a chuppa on a hill overlooking the ocean during a glorious sunset, followed by a dinner on the huge expanse of grass outside of the community's synagogue. From that time on, until the expulsion, we would spend a few days every summer at the Cohen home. We felt like we were in gan eden – Paradise. Once, when I needed some peace and quite to finish a writing project, I spent a few days there on my own.

In 1999, our daughter, Na'ama, married Avner Cohen, son of Ruti and Hezi Cohen of Ganei Tal. It was a chuppa on a hill overlooking the ocean during a glorious sunset, followed by a dinner on the huge expanse of grass outside of the community's synagogue. From that time on, until the expulsion, we would spend a few days every summer at the Cohen home. We felt like we were in gan eden – Paradise. Once, when I needed some peace and quite to finish a writing project, I spent a few days there on my own.

Before the expulsion, the Cohen's had suffered an unimaginable tragedy. Three weeks before they were uprooted from their home, Ruti's sister, Rachela, and her husband Dov, were shot dead by terrorists on the Tzir Kissufim road leading out of Gush Katif.

Ruti had two professions when they lived in Ganei Tal. She was a lab technician in the regional medical center that was unique in Israel and served as a model for others. "It functioned like a small out-patient hospital, and an ER," she says. "Everything was in the same location – the labs, the nurses, the doctors; they even performed small operations. Test answers were delivered on the spot and the patient would receive the necessary treatment then and there."

Ruti did not continue in this profession after the expulsion, as she had been employed by the regional council of Gush Katif, which was disbanded with the Disengagement. "I didn't have the strength to start looking," she says, "and nobody offered me help in that direction. That was even more difficult than losing my home – losing my work, losing the sense of getting up in the morning with somewhere to go. And I had loved it. The staff was like a family and I used to go to work with joy." In addition, she experienced a long period of deep mourning for her sister.

Hezi had worked in the Interior Ministry in Beer Sheva, so – unlike most of those in Gush Katif, especially the farmers, whose livelihood was destroyed – he was not left unemployed.

The Cohen's were among those who did not pack up their home in advance, though Hezi came in later to do so. Ruti walked out of their home with only a photograph of Rachela and Dov, and the yartzheit candle that she kept going for them.

They moved from a house of almost 170 square meters to a room of nine square meters.

Like the other members of Ganei Tal, they were sent to Kibbutz Hafetz Haim. They moved from a house of almost 170 square meters to a room of nine square meters. Several months later they were moved into a "caravilla" of 80 square meters, in Yad Binyamin, where they still are today. Caravillas are caravans that look like real homes but in fact are made of very fragile building materials and cannot be lived in long-term. Ruti says, "The most difficult thing of the size of the 'house' is that there is no kitchen, only a little corner with a small counter and a few cupboards."

Ruti’s second profession had been flower arranging and event designing, and she has continued to work in that area.. Ruti and Hezi also traveled a little after a year had gone by – to Thailand and Bulgaria, and they also won a lottery trip to Italy.

How does a day look for Ruti now?

"Very full, though almost without salary. I do work a few hours at two schools, preparing their science labs, but it's not what I would have chosen. I'm busy at home, and with the grandchildren, with family events, and I've been busy with my parents. I hope our new home will be ready by Pesach. Other families from our community have already completed the building; I was the one who held it up because I didn't have the strength to build, but it's difficult to be here now. Every time a new family moves into the rebuilt Ganei Tal [a short ride away, on lands that were purchased from Kibbutz Hafetz Haim], the government removes the 'caravillas.' We're among the last left."

There are seven grandchildren and great nieces and nephews named for Rachela and Dov Kol.

Bracha and Asaf Assis of Ganei Tal

In 2002, our daughter Noa married Amit Assis, who was living and studying in Jerusalem, but who also grew up in Ganei Tal. (The "shidduch" was my idea, when I met Amit on one of our visits to the Cohen's.)

In 2002, our daughter Noa married Amit Assis, who was living and studying in Jerusalem, but who also grew up in Ganei Tal. (The "shidduch" was my idea, when I met Amit on one of our visits to the Cohen's.)

Amit's parents, Bracha and Asaf Assis, did not have a life without challenges. Bracha had grown up in an orphanage and in kibbutz boarding schools. After high school she met Asaf and after the army they got married. Asaf, who had been an officer in the tank corps, lost his leg in battle during the 1969-70 War of Attrition, near the Suez Canal. Like most of the old-timers in Gush Katif, they were in their 50's when they were expelled from their homes and businesses and had to start over.

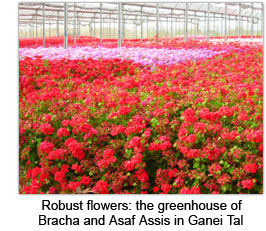

Asaf had been (and is, once again) one of the most successful geranium growers and exporters in Israel. He did not allow the business he had built over 30 years go down the drain. At his own expense (and considerable debt), with no help from the Disengagement Authority, he bought a large truck and hired someone to make several hundred trips, transporting geranium plants from the Gush to the outskirts of Ashkelon where, after a year of disappointments, and with the help of a few good people at the Ministry of Agriculture, he had located some land on which to rebuild his greenhouses. He also helped several other greenhouse farmers reestablish their businesses, creating a professional business group to bind them together.

After the expulsion the Assis family were also moved to Kibbutz Hafetz Haim and then to the caravilla site in Yad Binyamin. The regional council established a small shopping center, whose intention was to help the expellees from Gush Katif. It existed for several years. During that time, Bracha, who had owned a large, beautiful gift shop in Neve Dekalim, where she also sold her own ceramic wares, reopened a tiny shop and began to give ceramic classes again. She was helped in this venture by JobKatif, a grassroots organization created by Rabbi Yosef Tzvi Rimon that dedicates itself to helping the Katif expellees reestablish their businesses, open new businesses, and find jobs.

Bracha had to close her store about six months ago because the regional council closed down the shopping center when a large mall was built nearby. "Now," she says, "I'm just on 'sabbatical,' at home, and planning to someday open a ceramic teaching workshop near our home."

Bracha and Asaf moved into their new home this year in the rebuilt "Ganei Tal," that retains its original name.

”The wound is beginning to heal."

"It was medicine for the pain," she says. "Working on the planning and the building was occupational therapy. I feel calmer since we moved into our new home. After two months in Hafetz Haim and six years in Yad Binyamin, now that we're living in the new Ganei Tal, I can say that the wound is beginning to heal."

Bracha recalls the brit milah (circumcision) of Amichai, now seven years old, the second son of her daughter. His brit was the last one in Gush Katif. She remembers the trauma – for herself and for her relatives and friends -- of having to give a list of guests and their identity card numbers to the army in order for them to be allowed into the Gush to come to the brit.

Bracha recalls the brit milah (circumcision) of Amichai, now seven years old, the second son of her daughter. His brit was the last one in Gush Katif. She remembers the trauma – for herself and for her relatives and friends -- of having to give a list of guests and their identity card numbers to the army in order for them to be allowed into the Gush to come to the brit.

Right after her daughter gave birth, she wanted to recuperate in her mother's home. "I wanted to help her, to give her attention, but I didn't even have an orderly home in which she could rest after the birth," says Bracha. "Unlike some families, we did pack things up. We were working to put things in order; we would be taking pictures off the wall of the room where she was resting with the baby. I remember her finally standing in the doorway saying, sadly, 'I cannot be here with a baby,' and feeling the crunch in my heart as she went to her in-laws, who live a few minutes away, and who were not packing."

During those first years after the expulsion, Asaf would send money to his former Arab workers from Gaza, who – like many who worked in Gush Katif – suddenly found themselves without a livelihood. To this day he is in telephone contact with them. There were also workers who had come to Israel from Thailand, who continue to work for him. Asaf's oldest son, Adi, is now very involved in the business as well. Adi had lived in Tel Katifa, a beautiful seaside community in Gush Katif. He and his family are temporarily in Moshav Shekef and started building in what will be a new community, built from scratch, called Neta, just north of the Negev, not too far from Shomria.

In the first year after the expulsion, Bracha and Asaf traveled to Kenya, where they bought flowers to send directly to Europe, in order to maintain their customer base. Today the Assis greenhouses once again grow geraniums in reds, purples and pinks, as far as the eye can see.

Naama and Avner Cohen and the Community of Atzmona

About a third of the Atzmona residents were moved, after the Disengagement, to a community called Yated, in the Negev. Approximately a year ago, the community moved to Halutzit, about three miles from the Egyptian border.

About a third of the Atzmona residents were moved, after the Disengagement, to a community called Yated, in the Negev. Approximately a year ago, the community moved to Halutzit, about three miles from the Egyptian border.

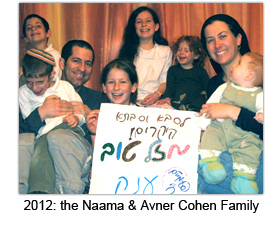

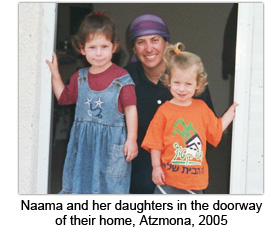

The other two-thirds of the community of Atzmona spent a year in tents and caravans in the "City of Faith," on the outskirts of Netivot, after which they were transferred to the grounds of Shomria, a former secular kibbutz that had only a handful of families left. The families were generously compensated to move out and the Atzmona families moved into the abandoned kibbutz homes and caravillas (as the kibbutz homes did not suffice). Our daughter, Naama, went to work in the local school. Our son-in-law, a career officer, was asked by Rabbi Avichai Ronsky, at that time the Chief Rabbi of the IDF (after the second Lebanon war), to join him as the director of his office. Several years later, Avner was promoted to Major, and moved to a new division within the army rabbinate that plans educational and Jewish awareness programs for soldiers.

During the year in between the expulsion and the transplanting of the Atzmona community to Shomria, Naama's family lived in Nof Ayalon, a religious community about half an hour from Avner's base in Ramat Gan. Nof Ayalon was in proximity to Kibbutz Shaalbim, that had taken in many of the Atzmona families after the expulsion. Naama and Avner had decided to spend a year there, rather than live in the "City of Faith." It was the only year in their married life that he was home at seven every evening.

I used to go there every Tuesday to help Naama with the children. Once while she was folding laundry, she showed me three of Avner's shirts, all torn from the collar downward. "This one," she said, "was the one on which he tore 'kriah' (the tear a mourner makes in his clothing) when he stood on the rubble of our home. This one," she said as she held up the second, "was the one he tore as he stood on the rubble of the home of his parents." Most residents, once expelled, had not been able to return, but as an officer, Avner had been permitted entrance to the Gush during and after the destruction of the community by the bulldozers.

And then she held up an army dress uniform shirt, with a jagged rip going down toward the heart. "And this one," she said, "is the one he tore when he heard on the radio that the last soldier had left Gush Katif."

"Our mourning was not only private," says Avner. "It was national mourning, that the people of Israel left part of our land."

Since the expulsion, three more children were born to Naama and Avner. Yehuda, Rachel Emunah and Hodaya.

The Gush Katif they knew and loved is memorialized in magnificent photographs on their living room walls -- a sunset from their home, a lifeguard's shack on the backdrop of the ocean, the synagogue of Atzmona. There are also photographs of Jerusalem, which, Avner says, "Connect Jerusalem and Gush Katif. Both were destroyed, yet the photographs of both show eternity – the sea, the sunset, Jerusalem's golden gates of mercy, symbolizing a final redemption."

My favorite photograph captures a large sign posted on a billboard at a lush, tree-lined Gush Katif crossroads. It says, "We'll be right back."

Photo credit: Toby Klein Greenwald