Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

11 min read

William H. Seward’s travelogue describes Friday Night Services at the Western Wall.

William H. Seward served as President Abraham Lincoln's Secretary of State. On the night of Lincoln's assassination, Seward was attacked in his home by one of Booth's co-conspirators and was seriously wounded.

But he survived, and in 1871 traveled the world and visited Jerusalem where he visited the "Wailing Wall" and participated in Friday night services, apparently at the Hurva synagogue.

His earlier visit to Jerusalem 1859 may have sparked an interest in President Lincoln to visit the Holy Land, evidenced in Mary Todd Lincoln's statement to the pastor presiding at Lincoln's funeral that her husband "wanted to visit the Holy Land and… was saying there was no city he so much desired to see as Jerusalem."

Below are excerpts from Seward's 788-page book, Travels around the World. The text below is interspersed with my comments:

June 13, 1871 – "Walk about Zion, and go round about her: tell the towers thereof. Mark ye well her bulwarks, consider her palaces; that ye may tell it to the generation following." [Psalms]

We have done so, and we have found it neither a short nor an easy promenade. The city occupies two ridges of a mountain promontory, with the depression or valley between them. The walls of the modern Turkish city have been so contracted with the decrease of the population, as to exclude large portions of the, ancient city. Jerusalem is now divided according to its different classes of population. The Mohammedans are four thousand, and occupy the northeast quarter, including the whole area of the Mosque of Omar.

In 1871, the Jewish population was double any other group in Jerusalem.

The Jews are eight thousand, and have the southeast quarter. These two quarters overhang the Valley of Jehoshaphat and the brook Kedron. The Armenians number eighteen hundred, and have the southwest quarter; and the other Christians, amounting to twenty-two hundred, have the northwest quarter, which overlooks the Valley of Hinnom.... [Note the Jewish population was double any other group in the Old City.]

The Jews throughout the world, not merely as pilgrims, but in anticipation of death, come here to be buried, by the side of the graves of their ancestors. As we sat on the deck of our steamer, coming from Alexandria to Jaffa, we remarked a family whom we supposed to be Germans. It consisted of a plainly-dressed man, with a wife who was ill, and two children – one of them an infant in its cradle. The sufferings of the sick woman, and her effort to maintain a cheerful hope, interested us. The husband, seeing this, addressed us in English. Mr. Seward asked if he were an English man. He answered that he was an American Jew, that he had come from New Orleans, and was going to Jerusalem.

We parted with them on the steamer. The day after we reached the Holy City we learned that the poor woman had climbed the mountain with her husband and children, and arrived the day after us. She died immediately, and so achieved the design of her pilgrimage. She was buried in this cemetery [on the Mt. of Olives]. She was a Jewess, and, according to the Jewish interpretation of the prophecies, the Jew that dies in Jerusalem will certainly rise in paradise.

June 15th. – "And the name of the city from that day shall be, the LORD is there."

June 15th. – "And the name of the city from that day shall be, the LORD is there."

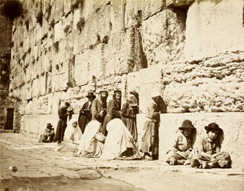

Our last day at Jerusalem has been spent, as it ought to have been, among and with the Jews, who were the builders and founders of the city, and who cling the closer to it for its disasters and desolation. We have mentioned that the Jewish quarter adjoins, on the southeast, the high wall of the Haram [The Haram el-Sharif, or Temple Mount]. This wall is a close one, while the upper part, like all the Turkish walls of the city, is built of small stone. The base of this portion of the wall, enclosing the Mosque of Omar, and the site of the ancient temple, consists of five tiers of massive, accurately-bevelled blocks. It is impossible to resist the impression at first view, notwithstanding the prophecy, that this is a portion of the wall of the Temple of Solomon, which was hewn in the quarries and set up in its place without the noise of the hammer and the axe. So at least the Jews believe.

For centuries (we do not know how many) the Turkish rulers have allowed the oppressed and exiled Jews the privilege of gathering at the foot of this wall one day in every week, and pouring out their lamentations over the fall of their beloved city, and praying for its restoration to the Lord, who promised, in giving its name, that he would "be there." [Seward reports that Jews were permitted access to the Wall only one day a week, Friday.]

Jews were permitted access to the Western Wall only on Fridays.

The Jewish sabbath being on Saturday, and beginning at sunset on Friday, the weekly wail of the Jews under the wall takes place on Friday, and is a preparation for the rest and worship of the day which they are commanded to "keep holy." The small rectangular oblong area, without roof or canopy, serves for the gathering of the whole remnant of the Jewish nation in Jerusalem. Here, whether it rains or shines, they come together at an early hour, old and young, men, women, and little children – the poor and the rich, in their best costumes, discordant as the diverse nations from which they come.

They are attended by their rabbis, each bringing the carefully-preserved and elaborately-bound text of the book of the Lamentations of Jeremiah, either in their respective languages, or in the original Hebrew. For many hours they pour forth their complaints, reading and reciting the poetic language of the prophet, beating their hands against the wall, and bathing the stones with their kisses and tears. It is no mere formal ceremony.

During the several hours while we were spectators of it, there was not one act of irreverence or indifference. Only those who have seen the solemn prayer-meeting of a religious revival, held by some evangelical denomination at home, can have a true idea of the solemnity and depth of the profound grief and pious feeling exhibited by this strange assembly on so strange an occasion, although no ritual in the Catholic, Greek, or Episcopal Church is conducted with more solemnity and propriety.

Though we supposed our party unobserved, we had scarcely left the place, when a meek, gentle Jew, in a long, plain brown dress, his light, glossy hair falling in ringlets on either side of his face, came to us, and, respectfully accosting Mr. Seward, expressed a desire that he would visit the new synagogue, where the Sabbath service was about to open at sunset. Mr. Seward assented.

A crowd of "the peculiar people" attended and showed us the way to the new house of prayer, which we are informed was recently built by a rich countryman of our own whose name we did not learn. It is called the American Synagogue. [The description is of the Hurva Synagogue; the nearby domed Tiferet Synagogue was not inaugurated until 1873. The writer is apparently mistaken about the American donor. The most likely foreign philanthropist to have been credited with building the Hurva is Moses Montefiore of England or Alphonse or Edmund de Rothschild of France.] It is a very lofty edifice, surmounted by a circular dome. Just underneath it a circular gallery is devoted exclusively to the women.

A crowd of "the peculiar people" attended and showed us the way to the new house of prayer, which we are informed was recently built by a rich countryman of our own whose name we did not learn. It is called the American Synagogue. [The description is of the Hurva Synagogue; the nearby domed Tiferet Synagogue was not inaugurated until 1873. The writer is apparently mistaken about the American donor. The most likely foreign philanthropist to have been credited with building the Hurva is Moses Montefiore of England or Alphonse or Edmund de Rothschild of France.] It is a very lofty edifice, surmounted by a circular dome. Just underneath it a circular gallery is devoted exclusively to the women.

Aisles run between the rows of columns which support the gallery and dome. On the plain stone pavement, rows of movable, wooden benches with backs are free to all who come. At the side of the synagogue, opposite the door, is an elevated desk on a platform accessible only by movable steps, and resembling more a pulpit than a chancel. It was adorned with red-damask curtains, and behind them a Hebrew inscription. Directly in the centre of the room, between the door and this platform, is a dais six feet high and ten feet square, surrounded by a brass railing, carpeted; and containing cushioned seats. We assume that this dais, high above the heads of the worshippers, and on the same elevation with the platform appropriated to prayer, is assigned to the rabbis.

We took seats on one of the benches against the wall; presently an elderly person, speaking English imperfectly, invited Mr. Seward to change his seat; he hesitated, but, on being informed by Mr. Finkelstein that the person who gave the invitation was the president of the synagogue, Mr. Seward rose, and the whole party, accompanying him, were conducted up the steps and were comfortably seated on the dais, in the "chief seat in the synagogue." On this dais was a tall, branching, silver candlestick with seven arms. [Pinchas Rosenberg, the Imperial Court tailor of St Petersburg donated a silver candlestick in 1866.]

Seward was invited to occupy the "chief seat in the synagogue."

The congregation now gathered in, the women filling the gallery, and the men, in varied costumes, and wearing hats of all shapes and colors, sitting or standing as they pleased. The lighting of many silver lamps, judiciously arranged, gave notice that the sixth day's sun had set, and that the holy day had begun. Instantly, the worshippers, all standing, and as many as could turning to the wall, began the utterance of prayer, bending backward and forward, repeating the words in a chanting tone, which each read from a book, in a low voice like the reciting of prayers after the clergyman in the Episcopal service. It seemed to us a service without prescribed form or order.

When it had continued some time, thinking that Mr. Seward might be impatient to leave, the chief men requested that he would remain a few moments, until a prayer should be offered for the President of the United States, and another for himself. Now a remarkable rabbi, clad in a long, rich, flowing sacerdotal dress, walked up the aisle; a table was lifted from the floor to the platform, and, by a steep ladder which was held by two assistant priests, the rabbi ascended the platform. A large folio Hebrew manuscript was laid on the table before him, and he recited with marked intonation, in clear falsetto, a prayer, in which he was joined by the assistants reading from the same manuscript. We were at first uncertain whether this was a psalm or a prayer, but we remembered that all the Hebrew prayers are expressed in a tone which rises above the recitative and approaches melody, so that a candidate for the priesthood is always required to have a musical voice.

At the close of the reading, the rabbi came to Mr. Seward and informed him that it was a prayer for the President of the United States, and a thanksgiving for the deliverance of the Union from its rebellious assailants [the just-concluded Civil War]. Then came a second; it was in Hebrew and intoned, but the rabbi informed us that it was a prayer of gratitude for Mr. Seward's visit to the Jews at Jerusalem, for his health, for his safe return to his native land, and a long, happy life. The rabbi now descended, and it was evident that the service was at an end.

[end of excerpt]

After Friday night dinner with the American Consul General, Seward and his party left Jerusalem the next day for Damascus, Beirut and European capitals. He returned to the U.S. in October and died the following year. His travelogue was published posthumously by his son in 1873.

Seward’s account of his encounter with the Jewish community in Jerusalem 140 years ago is an important addition to the history of American involvement with the Jews of Palestine. American ties to a Jewish homeland predates Israel’s founding in 1948 and even the formal establishment of the political Zionist movement in the 1880s. The relatively large population of Jews in Jerusalem that Seward discovered in 1871 is testimony to the age-old Jewish dedication to Jerusalem.

Courtesy of israeldailypicture.com.