An Open Letter from Jewish Students at Columbia

An Open Letter from Jewish Students at Columbia

9 min read

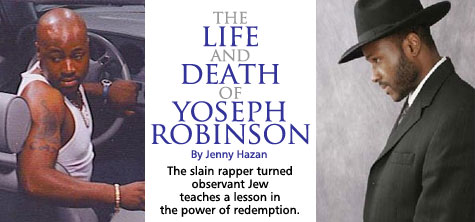

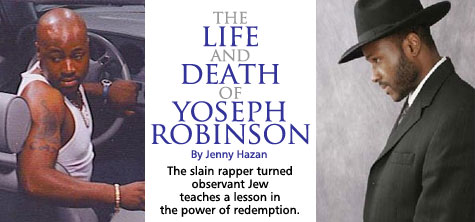

The slain rapper turned observant Jew teaches a lesson in the power of redemption.

The first time Yoseph Robinson z'l stared down the barrel of a gun was 15 years ago, when the Bronx drug dealer was betrayed by a colleague in crime. It changed his life. Robinson, then 19, quit life on the street filled with drugs and crime and embarked on a path that would eventually guide him from his post as a successful Hip Hop recording exec in L.A., to Orthodox Judaism. On August 19, the 34-year-old father of four was shot a second time, this time fatally, in Flatbush, Brooklyn, at the MB Vineyards kosher liquor store where he worked.

“It’s like his tragic death closed a circle,” says owner of MB Vineyards Benjy Ovitsh, 39, Robinson’s employer and close friend, who was on vacation when the crazed gunman entered the store and shot Robinson in the chest and arm for protecting the woman he was dating, Lahavah Wallace, from the robber.

Ovitsh and Robinson met two years ago, when Robinson first returned to Brooklyn from L.A., where he had converted to Judaism, married, divorced, and was at the time of his death entrenched in a custody battle over his 6-year-old daughter Chana.

The pair met through a mutual friend at Khal Zichron Mordechai synagogue in Brooklyn. Soon after, Robinson began working at the store, where he quickly became a fixture.

“People used to come into the store just to see him. He was warm and open, always up for a good conversation or debate,” Ovitsh told Aish.com. “He really made a Kiddush Hashem (sanctification of God's Name) every single day. He affected everybody.”

Ovitsh is confident that Robinson himself would see his own tragic demise as some sort of poetic closure, since that is how he viewed his life in general and his path to Judaism in particular. Robinson saw his conversion, at age 23, as the culmination of a series of seemingly unconnected events that inspired him to conclude, as Ovitsh says, “that he didn’t choose Judaism, Judaism chose him.” Says Ovitsh, “He sometimes said he was ‘kidnapped by Judaism.’”

Disenchanted with the Hip Hop lifestyle, he searched for something deeper.

Another close friend of Robinson’s from Brooklyn, Shais Rison (aka MaNishtana), 28, a fellow "Jew of Color," concurs. “Yoseph's faith was extremely strong and he always believed that everything that happened was from Heaven. He didn’t believe in coincidences,” he says. “If something didn’t go the way he’d have liked, he’d sometimes spend hours trying to figure out the good in it, or why it might have happened. He really embodied the maxim gam zu l’tova – this too is for the good.”

Chester’s No Exit

Robinson’s journey to Judaism may have begun as early as birth. Apparently his paternal grandfather was a Jew, a fact that meant little to Robinson throughout most of his life, but eventually became very significant to him. It was an Orthodox Jewish family from Borough Park, for whom Robinson’s mother worked as a nanny, which sponsored his immigration papers to the U.S. at the age of 12, from his birthplace in Spanish Town, Jamaica. When he arrived in Brooklyn his first after-school job was delivery boy for a kosher grocery store, which brought him in close proximity with the community he would eventually become part of.

After his brush with death, the high school dropout (born Chester Robinson) turned from his life of street crime and violence and moved to California, where he became CEO of No Exit, a record label in L.A. He found material success, drove a Lamborghini and had all the bling one could want. But he quickly grew disenchanted with the materialism of the Hip Hop lifestyle and continued his search for something deeper.

Ovitsh tells the story of Robinson’s first conscious encounter with Judaism. It all started with the botched delivery of Robinson’s plasma screen TV, which inspired him to take up reading instead. One day, he went book shopping and accidentally wandered into a Judaica shop in San Fernando Valley, a Jewish area where he had moved to live with his (Jewish) girlfriend at the time.

Robinson had settled on reading the Bible, after seeing copies of it in the many hotels he would frequent throughout his career in the music industry. When the clerk asked if he wanted a copy of the New Testament or the Old Testament, Robinson didn’t understand the difference and by fluke settled on the Old Testament, since it sounded more authentic.

“That was it. He was inspired by what he read,” says Ovitsh. “This was one of many little connections to Judaism throughout his life.”

As he showed more signs of curiosity about Judaism, his girlfriend bought him a prayer book and Robinson began attending services as a local shul. Finally, in 1999, Robinson converted under the auspices of the Los Angeles Beit Din, a process that took two-and-a-half years.

The process was not without tumult for Robinson. He faced some challenges transitioning to the Jewish community as a black man, and dedicated much of his time to bridging the gap between Jews and blacks, via community outreach and speaking engagements at local synagogues and schools, activities which he continued when he moved back to Brooklyn from L.A.

He lived according to standards of ethics and integrity that few of us can ever attain.

As he wrote on his website (yosephrobinson.com), “In Judaism, it’s the soul, the neshama that constitutes the person. The concept is spiritual and can embody any vehicle or physical body. Once people are able to aceept the idea that spirituality is not physical and is not bound by space or time, then a black Jewish man is easy to accept.”

“He was very proud of being Jewish, and very proud of being Jamaican, and he didn’t see them as contradictory,” comments Ovitsh.

All the details of Robinson’s Jewish journey were to appear in his memoirs, Jamaican Hip Hopper Turn Orthodox Jew, slated for release in December 2010. Ovitsh, who was helping him with the book, still hopes to get it out on time. “I would like to do that, as an honor to his memory,” says Ovitsh.

Rabbi Shlomo Rosenblatt met Robinson at Rabbi Moshe Tuvia Lieff’s shul, the Aguda of Avenue L, where Robinson often attended weekday services.

Rabbi Shlomo Rosenblatt met Robinson at Rabbi Moshe Tuvia Lieff’s shul, the Aguda of Avenue L, where Robinson often attended weekday services.

“He was a member of the community. He was well-loved throughout the entire community. Everyone enjoyed his company tremendously,” says Rabbi Rosenblatt, who recalls with fondness the Shabbatot, Sukkot, and Rosh Hashana festivals Robinson spent with his family. “He was a very warm, spiritual, charismatic person, positive, always smiling and upbeat. We were honored to have him as a family friend.”

Rabbi Kenneth Auman of Young Israel of Flatbush, where Robinson often took in Shabbat services, says Robinson touched so many people in the community because of his openness, and his attendance at all types of synagogues throughout the Flatbush community.

“You couldn’t pigeonhole him,” says Rabbi Auman. “He fit in everywhere.”

Minyan in Jamaica

On his death, the outpouring from the community was overwhelming. Hundreds of people showed up at his memorial service. In addition, with the help of Borough Park’s charitable burial organization Chesed Shel Emes, 10 men from the community flew to Jamaica to ensure the presence of a minyan at Robinson’s funeral in Spanish Town.

Yoseph showed that you are not stuck with the hand you are dealt.

Robinson’s family insisted he be buried in the backyard of his childhood house, alongside his grandmother Pearl, who raised him until he left for the U.S. Although Jewish community members preferred he be buried in a Jewish cemetery, they respected the family’s wishes, and agreed to hold as kosher a ceremony as possible under the circumstances.

“This is the fulfillment of ‘meis mitzvah’, when a Jew passes away and there are no Jewish next of kin to take care of the burial,” explains Rabbi Auman, one of the 10 minyan members. “Many people from the community contributed generously to send us. That just goes to show how people felt about this and about him.”

Rabbi Auman’s fondest memory of Robinson is how he behaved during services. “I have this image of him standing in the shul. He always sat in the same spot. He stood there so proud, and prayed with such intensity. He took the service very seriously. This is how I will remember him.”

Ovitsh recalls how Robinson once found an unmarked envelope full of cash in the liquor store. Robinson insisted he put it aside and wait for someone to claim it, even though according to Jewish law it was hefker – legally ownerless.

He transformed himself, emotionally and spiritually, into the person he wanted to become.

A few days later, an elderly non-Jewish customer came in, asking about the envelope. When Robinson handed it over, the man was moved to tears. Robinson explained to him that it is a mitzvah, a valued deed, for Jews to return lost objects to their rightful owners.

“That man will forever see Jews in a special light,” says Ovitsh. “Yoseph was a man of great honesty and integrity.”

What Rabbi Rosenblatt remembers most about Robinson is his generosity. “Our job in the world is supposed to be giving, and he lived to give,” says Rabbi Rosenblatt, who recalls a happy time when Robinson came over to their house with bags of fresh ingredients to share his famous jerk sauce recipe with the family. “He loved to share with others and give to others. He was really a giver and that’s how he left the world – with one final act of giving.”

“Yoseph's life shows that you really can change, that you are not stuck with the hand you are dealt," says Rabbi Auman. "You can rise above whatever difficulties and challenges you have. His life was an example of that.”

Rison agrees. “He was extremely proud telling of the trouble he’d gotten into and been around – not for the sake of bragging about how bad he used to be, but as a source of pride for how far he’d come,” he says. “Yoseph was a pillar for black men, a pillar for Jews, a pillar for Jews of color, and a pillar for our generation.”

“Yoseph wanted to demonstrate that a person can change, regardless of who you were or what you did,” said Ovitsh in his eulogy at Robinson’s memorial service in Borough Park. “He transformed himself, emotionally and spiritually, into the person he wanted to become. That’s what makes him so unique. He was flawed, as all of us are flawed, but he tried to improve himself. And he succeeded, day after day, to become a better human being. He lived his life according to standards of ethics and integrity that few of us can ever attain.”