X-Men ’97 Reflects the Fears and Hate Jews Are Feeling

X-Men ’97 Reflects the Fears and Hate Jews Are Feeling

6 min read

The everlasting message of tefillin -- from Bergen-Belsen to a Jerusalem oncology ward.

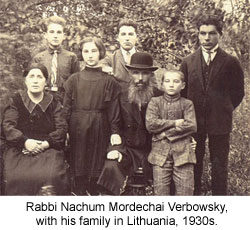

My great-grandfather, Rabbi Nachum Mordechai Verbowsky, was the rabbi of the Lithuanian town of Akmian. Sixty-seven years ago, he put on Tefillin for the very last time.

Before the war, the Akmian numbered some 300 Jewish families, Mazeik 500, and Vekshne 200. In the summer of 1941, these three Lithuanian towns bore the brunt of Nazi brutality.

Before the war, the Akmian numbered some 300 Jewish families, Mazeik 500, and Vekshne 200. In the summer of 1941, these three Lithuanian towns bore the brunt of Nazi brutality.

On the day the Germans entered, all the Jews, together with their rabbis -- including my great-grandfather -- were rounded up and taken to the dense forest of Tirkshle.

Led by their rabbis, the Jews courageously marched toward death.

The rabbis knew they were being taken to their execution, and so they donned tallit and tefillin. It was an imposing spectacle -- the mass of Jews, led by their rabbis, courageously marching to their deaths.

The aged Vekshne Rabbi called on the Jews not to despair, and not to show the Germans the slightest trace of fear. If it was their fate to die the deaths of martyrs, and thus sanctify the name of the Almighty, they should die as proud members of the ancient Jewish people.

The Nazis then turned their machine guns and rifles on the Jews, who died with cries of "Shema Yisrael" on their lips.

After Bergen-Belsen

My grandfather on my mother's side, Rev. Leslie Hardman, was the British Army chaplain at the liberation of Bergen-Belsen. He had to bury thousands of Jews in mass graves. I have no idea what he was feeling or thinking, but I know that from somewhere, from the deepest point of eternity within him, he found the strength and the courage to stand at the edge of those graves and say the Kaddish prayer.

He may even have been the only Jew at that mass funeral. But he represented life. He represented hope.

My grandfather used to tell the stories of those horrific days after the liberation.

On one occasion, a shivering, emaciated individual knocked on the door of his makeshift office, asking for food.

"Herr Rabbiner, I haven't eaten anything for days. Do you have a bit of bread?"

My grandfather opened one of the cupboards and saw a few tins of sardines. He stretched up to get them, when the man said, "Wait. What's that there?"

Next to the tins was a blue velvet bag.

"They're tefillin," said my grandfather.

The man's eyes, barely in their sockets, began to well up with tears.

"I haven't put on tefillin for three whole years."

"I haven't put on tefillin for three whole years. Would you mind?"

My grandfather watched as the man lovingly and carefully opened the bag, gingerly taking out the tefillin as if they were the rarest diamonds in the world.

As he heard the man recite the blessing, my grandfather couldn't take it any more, and he left the room, incapable of restraining his tears.

Tefillin on the Leg

Emil Herman, 84, a friend of my in-laws, went through the Holocaust as a 16-year-old boy. He believes he survived (and helped others survive, too) thanks to his tefillin.

He managed to keep them hidden from the Nazis -- on death marches, in the camps, in jails in Hungary and Czechoslovakia, and in Vienna, as he was interrogated by the Communists after the war.

Through bitterly cold nights and snowbound days, barefoot, half-naked, tortured, hungry and thirsty, Emil Herman looked after his tefillin.

And his tefillin looked after him.

He wrapped them around his legs, hid them under stones and wooden planks, and somehow managed to put them on, pray and share them with others every day.

And he defiantly wore them again when he went back to the Mathausen concentration camp, some 60 years after suffering and surviving in that very same place.

Heads and Heart

The core of Jewish life is combining our powers of emotion, intellect and action to do the right thing: To do what God wants us to do.

To symbolize this, the arm-tefillin is placed near the heart, reminding us to control our emotions in the service of God.

The head-tefillin is near the brain, so that our intellect should be directed toward performing God's will.

The two powers then work together to bring us to proper action. We use all our resources to gain the full perspective, and then act with singular clarity of purpose.

As we put on the tefillin straps, we bind ourselves to Torah, to God, to eternity. Whether we're at death's door in a Nazi concentration camp, or suffering the effects of an economic slump, we strive to maintain the sanity and sanctity of our heads and hearts.

Rising Above the Pain

Two weeks ago, my son, Gilad Chaim Verbov, great-great-grandson of Rabbi Nachum Mordechai Verbowsky, put on tefillin for the very first time, in preparation for his bar mitzvah.

But this is no ordinary bar mitzvah.

But this is no ordinary bar mitzvah.

This time last year, Gilad was laying in a Pediatric Oncology unit in Jerusalem, undergoing chemotherapy for Burkitt's Lymphoma, a largely curable form of cancer.

It would be presumptuous to compare Gilad's ordeal with that of his great-great-grandfather, but we can proudly say that the eternal Jewish traits of controlled intellect and emotion -- symbolized by the tefillin on the head and arm -- were definitely visible as he bravely went through the treatment.

Gilad kept a clear head and a pure heart.

He kept his sense of humor, remained sensitive to others even when he was in pain, and never once used his situation to take advantage or make unreasonable demands.

He maintained a clear head and a pure heart.

And he never lost hope.

Indeed, the night after we were informed of the pathology results, before we'd started any treatment, we went home to absorb the bad news. One of the first things Gilad did was to draw a smiling face decorated with the words "Mitzvah gedola lihiyot besimcha tamid" -- It's a great mitzvah to always be joyful.

And now he's in full recovery, thank God.

Seeing a boy grow into manhood is a special thrill for any parent. With Gilad, the emotions are multiplied tenfold.

As I look at him, I know that the Jewish people still possess the mystical power of the tefillin.

A power beyond time and space.

A force greater than any Nazi or anti-Semite who ever lived.

A bond of eternity.

Click here to learn more about tefillin.