X-Men ’97 Reflects the Fears and Hate Jews Are Feeling

X-Men ’97 Reflects the Fears and Hate Jews Are Feeling

4 min read

11 min read

9 min read

7 min read

Is the $45 million spent on a Holocaust museum going to produce Jewish grandchildren?

Ten years ago my mother, a Holocaust survivor from Hungary, told me that she had given up on the idea of Holocaust museums.

It was a strange statement from a person who had suffered so much. By the age of five, my mother had become a virtual orphan: her father had been killed in a forced labor camp in the Ukraine and her mother had been marched off to Bergen-Belsen, from which she would only return after the war. After being passed first to her grandparents in the Jewish ghetto in Budapest and then to a gentile family, my mother was finally sheltered in a safe house for Jewish children established by the Red Cross. Even there she wasn't invulnerable. On at least one occasion Nazis raided the house and marched the children to the Danube River to be shot. At the last moment, her aunt plucked her from the roundup and she was saved.

My mother's statement wasn't cold-hearted. As a survivor growing up in a family of survivors and surrounded by a community of survivors in Skokie, Ill. where we lived, she was well aware that others had suffered fates far worse than her own. She had the utmost respect -- and still does -- for those people who had not only suffered the horrors of the war, but who had shown the courage and strength to rebuild their lives and the lives of their families after the war. As children, my siblings and I were regaled with stories of countless people who had transformed their once broken lives into flourishing ones. I remain awed by survivors' fortitude and count myself a blessed beneficiary of their collective strength.

No, my mother's statement wasn't cruel, it was merely practical. Taking the long view, she understood that the dilemma facing the Jewish community wasn't remembering the Holocaust, but producing the next generation of young Jews. She understood that a child without a good Jewish education was likely to assimilate and that a young Jewish man or woman who felt little connection to his or her history, culture and religion had a good chance of intermarrying, breaking a chain of thousands of years that countless others had fortified and protected.

While we are building museums to our past suffering, our people are disappearing.

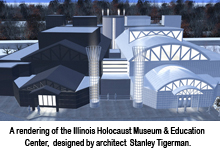

So it was with mixed feelings that I approached last week's opening of the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center, the latest, and probably the last, Holocaust museum to be built in the United States. On the one hand, I felt a great deal of civic pride. My little community, Skokie, Ill., would forever be on the Jewish map. In 1977, a small group of survivors had banded together to oppose a planned march of neo-Nazis. Their fight to keep the Nazis off Skokie streets (where a disproportionate number of Holocaust survivors had settled after World War II) is now credited with launching the Holocaust education movement in the United States. A large and impressive museum, with the imprimatur of President Obama, Elie Wiesel and others, is a monument to the persistence and determination of the Chicago survivor community.

But I can't help but feel that our priorities are misplaced. While we are building museums to our past suffering, our people are disappearing. The statistics are familiar and numerous: an intermarriage rate above 50 percent; little to no interest in synagogue life outside of observant circles; young people thoroughly disenchanted with and disconnected from the state of Israel. A population that has grown little since the end of the war despite the efforts of dedicated community professionals who have poured millions, if not billions, into nurturing Jewish life in the United States.

But I can't help but feel that our priorities are misplaced. While we are building museums to our past suffering, our people are disappearing. The statistics are familiar and numerous: an intermarriage rate above 50 percent; little to no interest in synagogue life outside of observant circles; young people thoroughly disenchanted with and disconnected from the state of Israel. A population that has grown little since the end of the war despite the efforts of dedicated community professionals who have poured millions, if not billions, into nurturing Jewish life in the United States.

Is the $45 million spent on a Holocaust museum going to produce Jewish grandchildren? Will it help a young Jew appreciate the depth and relevance of Jewish wisdom? Will it help young Jewish men and women understand why Jewish marriage is so vital for the survival of the community?

Offense, Not Defense

Maybe those are unfair questions. After touring the museum last Friday and attending a two-hour opening ceremony on Sunday, it became clear that the museum's mission isn't to reinforce Jewish identity, but to educate the public about genocide. Once visitors are compelled to understand the pure evil of the actors' motives and the helplessness of the victims', the argument goes, another Holocaust is less likely to occur.

This museum goes a step further than other Holocaust museums I have visited by explicitly juxtaposing the Shoah to other recent genocides -- Armenia, Cambodia, Rwanda -- in an attempt to universalize the message of Jewish suffering.

But I think the comparisons are only useful if you believe that educating someone about something as irrational as antisemitism will actually improve their behavior. But has Holocaust education even been effective? Did it prevent Hutus from raising machetes against Tutsis? Did it derail Serbian designs for Bosnian concentration camps? Did it stop the United Nations, the closest thing we have to a world government, from holding an "anti-racism" conference last week at which the president of a country that has called for the utter destruction of another was given top billing?

Holocaust museums is playing defense, not offense.

While I'm sure there have been people moved to action by a visit to a Holocaust museum and I'm certain they play an important role in education and commemoration, I do not believe they are crucial to the survival of our community. Ultimately, we will have to save ourselves.

First, let's realize that building Holocaust museums is playing defense, not offense. Creating an institution whose purpose is to teach visitors not to side with tyrants and persecute strangers is a wonderful ideal, but I think we can do more. I think we can teach them about Jewish suffering in particular and explore the ways that Jewish persecution and murder is totally different from that of others, as is the case at Israel's Yad Vashem.

Second, focus on the future and project strength, not weakness. As a Jewish journalist, I read nearly everything that affects the Jewish community and Israel. And over the past few years I have begun to feel that the communal obsession with the Holocaust is sending the wrong message to the world. It sends a message of weakness and not strength. It tells people that we are still licking our wounds, while our real strength lies in the incredible communities we have built after the war, communities that couldn't have been built without the enormous contributions of survivors. Ironically, the survivors have taught us a valuable lesson about how to live by moving forward with their lives. While we must remember, we should also heed their lesson by building Jewish life.

While we must remember, we should also heed the survivors' lesson by building Jewish life.

So what should we do? I believe there's only one answer. As much as trips to Israel might help build identity among American youth and cultural programming may convince them that being Jewish is "cool," a comprehensive Jewish education is the ultimate solution. Studies show that Jewish kids with a day school education are likely to affiliate with their community over a lifetime and in-marry -- at a rate above 90 percent. If we want to invest in our community, let's play offense. We need to build Jewish day schools and make them a top communal priority. Give Jewish kids a reason to be Jewish and we won't have to convince them to be Jewish later on.

Finally, let's consider not only the survivors but the 6 million martyrs who were murdered in the most heinous event in human history. What would my grandfather and other martyrs of the Holocaust have preferred: a monument to their suffering, or the knowledge that their children and grandchildren were living full, rich, prosperous Jewish lives?