Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

11 min read

Celebrating his bar mitzvah with his grandson, Harry Bibla attains the ultimate victory.

One week after Pesach 2015, friends and family of Matan Bibla – a soon-to-be thirteen-year-old from Toronto – opened their mail to find a surprising bar mitzvah invitation.

In addition to the invitation for the expectant young man, guests discovered that the celebration, in fact, would center on two bar mitzvah boys: Matan, and his grandfather, affectionately known as “Saba.”

“I never had a bar mitzvah,” Saba, or Harry Bibla explains. “At 13, I was running for my life. When Matan, my youngest grandson, began learning for the occasion, I realized this was my last chance. I said ‘I want a bar mitzvah too.’”

“I never had a bar mitzvah,” Saba, or Harry Bibla explains. “At 13, I was running for my life. When Matan, my youngest grandson, began learning for the occasion, I realized this was my last chance. I said ‘I want a bar mitzvah too.’”

Born in Miedzyrzec, Poland in 1930, Harry (Tzvi) Bibla – called “Hirsch” as a child – grew up in a bustling town of 15,000 where Jews comprised 75 percent of the population. The third of eight children, he attended the local public school and spent his afternoons roaming with friends. In 1940, however, the ten-year-old’s childhood was cut short: during a brutal aktion, Harry’s mother and younger siblings disappeared (to this day, their fate is unknown). In 1942, the surviving family members – Harry, his father, and two older brothers – were forced into the dilapidated, disease-ridden Międzyrzec ghetto. In this infamous ghetto, from which only 1 percent of the city’s pre-war population emerged alive, 20,000 Jews were crammed into an area designed for 1,400.

Harry found out that all ghetto residents had been dragged to the forest and gunned down.

“We lived nine people in one small room,” Harry remembers. “There was so much sickness.”

Liquidation of the ghetto was not long in coming. When Harry’s father – a devout, hardworking tailor – heard the operation was imminent, he grabbed his three sons and, joined by an uncle and family friend, hid in a nearby field. Hours later, Harry found out that all ghetto residents had been dragged to the forest and gunned down.

With limited options, the men fled to the nearby forest and joined a band of partisans. For three full years, the group of 25 subsisted on pilfered potatoes and radishes, occasionally snagging “treasures” like milk or eggs. The Biblas made a pact: if something terrible happened and the family was forced to disperse, survivors would meet up at a designated barn.

In January of 1944, a Polish farmer discovered the partisan camp. Fearing the Pole would snitch to the Nazis to earn a paltry sum of money, the chief partisan moved to kill him immediately. The man begged for mercy.

“I’m on your side,” he insisted. “I want to tell you that that war is almost over. The Russians are pushing the Germans out of Poland; you will survive.”

Hesitantly, the partisans let him go. That very night, they found themselves ambushed by SS guards – they’d been betrayed. Harry, the youngest partisan, managed to escape into the woods.

When I looked back, I saw the Nazis shooting my father close-range.

“When I looked back, I saw the Nazis shooting my father close-range,” he says. “They killed them all.”

For days, Harry wandered through the forest, armed with nothing but a will to live. Ultimately, he found refuge in a barn, where he surrounded himself with haystacks. A farmer discovered the emaciated boy and began bringing him one slice of bread each day. But after several weeks, the jittery benefactor had had enough.

“I’m afraid to keep you anymore,” he said. “Please leave.”

With nowhere to go, the forsaken teenager set out on a journey to oblivion. He passed three barns, then remembered that one of them was the designated safe place. Painfully, there would be no one to greet him: he was the only survivor.

Harry stumbled into the barn, his body shaking from hunger. Then he heard a noise from the next haystack: it was his brother, Chaim. Unbeknownst to him, Chaim had sustained a gunshot wound to his ankle but managed to hobble away from the forest massacre. Practically immobile, he was still nursing what had become an infected abscess, but had survived by eating potatoes and carrots dug out of the ground. After a tearful reunion, the brothers cared for each other until June of 1944, when the Russians came and liberated them.

“We were free people, free!” Harry remembers.

The brothers returned to their mother’s hometown, only to discover that nothing much had changed: their Polish neighbors were hostile, sometimes murderous. Chaim met up with a landsman, Rose, whose entire family had also perished. The couple married and set off for Canada, where Rose’s distant relatives lived.

Meanwhile, younger brother Harry made his way to France. On April 2nd, 1947, he boarded the Theodor Herzl, hoping to rebuild his life in Israel. After nearly two weeks at sea, the ship – carrying 2,641 passengers, mostly Holocaust survivors – was intercepted by the HMS Haydon and HMS St Brides Bay, two fearsome British destroyers. Passengers resisted heavily; three were killed and 27 were injured.

Eventually, the passengers capitulated, and like many before them, saw their ship redirected to Cyprus. Harry found himself in one of 12 detention camps housing 6,000 orphaned Jews. The British allowed 750 detainees to immigrate to Palestine each month. Eight months later, in December 1947, Harry finally disembarked on the Holy Land, moving to Kibbutz Maanit, a settlement established five years earlier by members of the Hashomer Hatzair group. Northeast of Netanya and near Wadi Ara, the community found itself on the front lines during the 1948 War of Independence and was attacked by the Iraqi Army. With a rifle in hand, Harry did his duty defending the kibbutz. Two years later, he was drafted into the Israeli Army, where he served as a foot soldier in charge of his unit’s radio communications.

Upon completion of Harry’s army service, Chaim asked his brother to join him in Canada, offering a visa and papers. The latter agreed, and in 1952, the brothers were reunited. Harry first worked as a carpenter and then began his career in the garment industry – using skills he’d been gifted by his murdered father.

In 1960, Harry travelled back to Israel and met his future wife Sara. They married in Israel, then several months later moved to Toronto. Harry continued to work in the garment industry and Sara began hairdressing.

The couple became valuable members of Toronto’s Jewish community, settling on Bathurst Street in the city’s upper edge. Eventually, they became the proud parents of three boys – Marvin, Steve, and Avi – and grandparents of 11 beautiful grandchildren.

Fifty-two blessed years went by until Sara, sadly, passed away in March 2012 after a valiant battle with cancer. Now alone but independent, Harry remained in his longtime home, minutes away from his family. He enjoyed frequent visits from grandchildren, including Matan – son of Steve and daughter-in-law Ariella.

Matan, an expressive young man who loves friends and sports, has a full head of brown hair and an irresistible personality to match. Family members describe him as unusually giving and considerate.

“Kishmo ken hu [his name encapsulates his essence],” says mother Ariella, citing a famous Jewish aphorism sourced in the words of the biblical Avigail. “He is a gift – to his parents, his community, and his friends.”

When the diligent seventh grader began studying his Torah portion with a rabbi in preparation for his bar mitzvah, Saba Harry – a frequent visitor – found himself drawn to the sessions. Observing the scene one day, it occurred to Steve that his own father, Saba, had never merited a proper bar mitzvah.

“What do you think about Saba having his own bar mitzvah?” Steve threw out to Ariella. They both agreed it would be incredibly meaningful, but were hesitant to bring it up. Would they trigger painful memories?

Thankfully, Saba resolved the dilemma: he brought it up on his own.

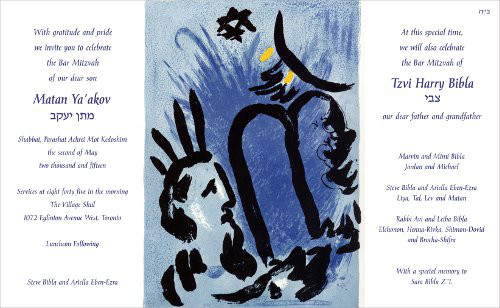

Ariella, a graphic artist, was immediately inspired with a creative design. On the left side of the invitation, she included standard celebratory text for Matan. On the right side, she printed: “We will also celebrate the bar mitzvah of Harry Bibla,” signed by the “hosts” – his many loving children and grandchildren. Fittingly, her striking illustration featured an image of Moshe receiving the Torah at Sinai.

“It was a privilege,” Ariella says of creating the invitation.

In the meantime, Saba studied with Rabbi Chanan Gans – Matan’s devoted rebbe – to prepare his own Torah portion. Ariella’s mother, Hannah Eben-Ezra, flew in from Israel for the occasion and brought two Jerusalem-made tallitot: one for Matan, and one for Saba.

Rabbi Ahron Hoch, rabbi of Aish HaTorah’s Village Shul in Toronto and a mentor of the Biblas, sent out an email to the greater community: he wanted residents to know about this unique event. The response was overwhelming: on Shabbat of parashat Achareimot-Kedoshim – a double portion for a double bar-mitzvah – men and women from across Toronto streamed into the shul.

“The place was packed,” Rabbi Hoch recalls. “It was an unusual attendance, even for a bar mitzvah.”

Minutes before Saba’s aliyah (the formal call to the Torah), Rabbi Hoch prepared the congregation for the cross-generational ceremony. With unconcealed emotion, he distilled the legacy of the akeidah – Abraham’s near sacrifice of his son Isaac – and suggested that this occasion was a manifestation of that legacy.

Minutes before Saba’s aliyah (the formal call to the Torah), Rabbi Hoch prepared the congregation for the cross-generational ceremony. With unconcealed emotion, he distilled the legacy of the akeidah – Abraham’s near sacrifice of his son Isaac – and suggested that this occasion was a manifestation of that legacy.

“The akeidah was such a difficult trial that Abraham later beseeched G-d: Never test me like that again!” Rabbi Hoch noted.

“But Abraham passed the test, and in doing so, transmitted a gene for eternity. His offspring have endured unimaginable horrors for millennia. Yet even when they’re justifiably angry and bitter and disillusioned, an overwhelming majority still relate to G-d, still acknowledge Him in their own way. There is no rational explanation for this inextinguishable spark, irrepressible longing.

“We stand today before a Holocaust survivor who was left with throbbing questions. Harry Bibla could have turned his face on Judaism, and no one would have judged. And yet he arrived on these shores and sacrificed comfort so each of his children could receive a Jewish education. And seven decades after watching his entire family butchered, he, too, decided to have a bar mitzvah.”

“Harry Bibla,” Rabbi Hoch concluded, “is a living example of the ‘akeidah Jew.’ Today, we have merited to participate in the joy of a great man.”

Then it was time. Harry Bibla, at 85 years old, was called up for shlishi (the third Aliyah). Slowly, amid near total silence, he walked to the platform. The entire shul stood up.

“Saba became choked up,” Ariella relates. “He is not an emotional person. In the 21 years that I know him, I have never seen him that way.”

For the first time in his life, Saba carefully read some Torah verses, then made the concluding blessing. Moments later, Matan was joyously called up, and his many months of work paid off with a beautiful reading.

For the first time in his life, Saba carefully read some Torah verses, then made the concluding blessing. Moments later, Matan was joyously called up, and his many months of work paid off with a beautiful reading.

“I wouldn’t have wanted it any different,” Matan later said of the joint celebration. “It was an honor. It was everything I could’ve asked for.”

Matan shared a personally-prepared Torah thought with the receptive crowd.

“Celebrating my bar mitzvah with my Saba is living proof that we, as a nation, are still very much alive.”

“I do not think it is a coincidence that the names of the parshiot this week mean ‘after the death of the holy ones,’ he said. “ This week we commemorate the liberation of the survivors of Auschwitz. Celebrating my bar mitzvah with my Saba is living proof that we, as a nation, are still very much alive….. I hope that in honoring my Jewish identity as a Bar Mitzvah, I will give my Saba, and all survivors, the honor they deserve.”

For Ariella and Steve – and every person in the hall – it was an unforgettable moment.

“Watching Saba finally get his bar mitzvah, then pass down the legacy…it was the ultimate victory,” Ariella reflects. “Through him, we won. We won.”

A version of this article originally appeared in Mishpacha Magazine.