Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

8 min read

An exciting exhibit presents direct evidence of the Jewish community in Babylonia right before and after the destruction of the First Temple.

Those of us fascinated by the ability of archaeology to bring to life ancient Jewish history and to remind us of our historical continuity are now being presented, for the first time, with direct evidence of the Jewish community established in Babylonia right before and after the destruction of the First Temple. While these finds were partly known to scholars for some years, the first public presentation of these documents took place on February 1 with the opening of a full-scale exhibit and scholarly conference devoted to these important texts at the Bible Lands Museum in Jerusalem. The large crowds of scholars and lay people that continue to fill the museum each day signal the tremendous importance of these tablets being exhibited.

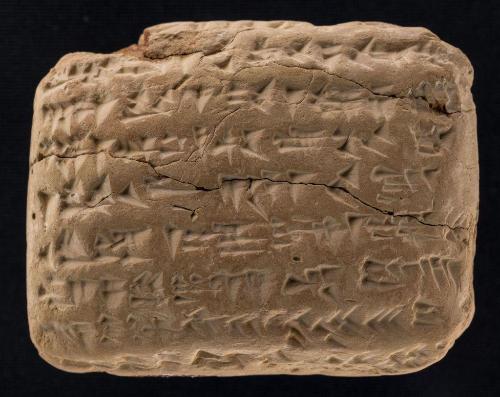

We now have over 100 clay tablets, written in the Babylonian language in cuneiform script, testifying to the economic life and the religious continuity of Jews exiled to Babylonia. We can expect in a short time the publication of about 90 more such tablets held in other collections. Many come from a Jewish settlement, Yehudu, Judeatown, located in the area south and southeast of Baghdad.

A clay tablet from 572 BCE, the earliest known text documenting the Judean exile in Babylonia, now on display at the Bible Lands Museum (photo credit: Ardon Bar-Hama courtesy of The Bible Lands Museum)

The eighth century BCE saw a series of three exiles, in which inhabitants of the northern kingdom of Israel were brought to Assyria in northern Mesopotamia and spread east to Medea (today’s northern Iran) and even further. The conquest of the Assyrian Empire by Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon in the early seventh century BCE opened the way for the Babylonians to demand tribute from Judea. Hoping for help from Egypt, Judea twice rebelled against its Babylonian overlords, first under King Yehoiachin (Yechoniah in Esther 2:6), who was then deposed and exiled to Babylonia, and then 11 years later under Zedekiah, whose refusal to remain a vassal of Babylonia led to the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple, and a further large-scale exile to Babylonia. Both the Bible (Melachim II 25:28-30) and the Babylonian Chronicle indicate that Yehoiachin and his sons ate from rations provided by the Babylonian government for such exiled rulers of conquered territories. The prophet Ezekiel was taken in the first deportation to Babylonia, along with various members of the elite and artisan classes. Throughout this period, Jeremiah cautioned against reliance on Egypt, counseling the paying of tribute to Babylonia to maintain Jewish independence and freedom.

The newly published texts testify extensively to the presence of this Babylonian exilic community and to its various economic and agricultural activities. This becomes even more important when we remember that these Judeans lived in the very same area in which much later, from the third through seventh centuries and beyond, the Jewish community flourished, eventually leading to the completion of the Babylonian Talmud.

What is really in these tablets? What do they tell us about the life of our ancient forebears?

The texts in the now-published David Sofer collection are dated using the names of the various rulers between 572 and 477 BCE. They were written soon after the destruction of the Temple, through the fall of the Babylonian Empire and its conquest by Cyrus the Great of Persia, and up into the Persian period. As such, this collection spans the years of the return to Judea and the restarting of Temple worship in Jerusalem.

The most important thing about these tablets is most probably the names that occur in them. Here we have Jews undertaking business and personal transactions with other Jews as well as with Babylonians and exiles from other places, in areas with significant populations of Judean exiles. We see how quickly Jews acclimated to the prevailing conditions, engaging in a variety of business and agricultural activities while maintaining their identity. The maintenance of names bearing traditional Jewish divine elements indicates Jewish identity and, where we are able to trace generations, Jewish continuity as well. The 103 published texts mention more than 75 such personal names that refer to approximately 120 individuals. Where relationships can be established from multiple texts, we learn that some Jews bore Babylonian names.

Some of these names are known from the Bible and in many cases, even if not previously known, seem typical of the types of names we encounter, especially in the Books of Ezra and Nehemiah. Speaking of Nehemiah, for example, the name Nachim-Yama in our text is the very same name. Nadav-Yama is Nadavyah, and so on with many of these names. Yahu-azar is Yoezer. There is even a Haggai and a Zakar-Yama, that is, Zechariah, not to mention a Yarim-Yama, Yirmiyahu. This is not to say that the well-known personages with these names are mentioned in these texts; rather, that these were common names held by other Judeans as well. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who was thrilled to find out that there was a seal impression with his last name from the Biblical period, will no doubt be happy to learn that Natan-Yama is the Babylonian realization of Netanyahu. You can probably already figure out that sometimes the sound of the Hebrew vav, originally pronounced like a “w” (as in Iraqi Hebrew and in Arabic), was realized as “m” in the Babylonian language.

Previous to the publication of this discovery, we were in possession of the archives of the Murashu banking house from Nippur in Babylonia, stretching for about 50 years beginning in 450 BCE. In these documents, Jews feature prominently as witnesses to a variety of legal transactions. The Yahudu tablets, when taken together with the previously known Murashu tablets, allow us to trace the continuity of the Jewish community in Babylonia from the exile through the end of the Biblical period.

These newly-published tablets clearly show that the exiles took the advice sent by Jeremiah to the first wave exiled with Yehoiachin to build houses and settle (Yirmiyahu 29:5, 28) since they would be in exile for at least 70 years. But they also show, as we already knew from the Bible, that much of the community remained in Babylonia despite the opportunity to return to Eretz Yisrael. Clearly, as we can now see, their economic integration and success were a big part of that decision to remain. To show the variety of Jewish economic activity, here is a list of the types of documents preserved: promissory notes regarding commodities, receipts for payment, slave sales, lease of land, receipts for payment of loans, a marriage deed, sale documents pertaining to animals, house rentals, complex arrangements for assembling a team of animals for plowing, partnership contracts and court decisions.

Many of these documents stem from the financial arrangements that were made when the exiles were settled in areas of Babylonia by their Babylonian conquerors. Land was parceled out, and this was certainly the case in Yahudu, to farmers who would in turn pay percentages of their crops to the government in return. In a sense, most of the Jewish inhabitants of these small villages were engaged in a land-for-service arrangement in which shares of their crops served as their rent. This arrangement was known to have been used widely in ancient Babylonia. Those with agricultural skills and business acumen were able to turn the situation to their advantage and to succeed financially, despite the difficulties of the experience of exile. This is certainly one of the definite conclusions that emerge from the study of this material.

Unfortunately, beyond their names, these texts contain little information about the religious beliefs and practices of these Jewish exiles. This is because they are economic documents written by Babylonian scribes who functioned essentially as the lawyers of that period. Here is an example of one of the texts, dating to 23 Tevet, 550 BCE: “[13] kor of barley are owed to Gamul son of Bi-hame [most probably a non-Jew] by Shelemiah son of Nadavyah. In the month of Sivan he [Shelemiah] will deliver the barley in its principal amount in the city of Adabilu. Delaiah son of Ilishu guarantees for delivery of the barley” (adapted from translation by L. Pierce and C. Wunsch). This Shelemiah even signed his name in ancient Hebrew script on the side of the tablet.

The Jews making the various arrangements, either among themselves or with non-Jews, needed to fulfill the requirements of the local legal system in order to be legally protected in the various endeavors. Accordingly, the documents generally fulfill the same legal procedures that one finds in non-Jewish legal documents from Babylonia in the same period. We should also note that these documents concern the rural population, but we would expect that some Jews, such as the families from which Ezra and Nehemiah emerged, probably lived in larger population centers.

Readers of these tablets who are familiar with the occupations and economic circumstances that are in evidence in the Babylonian Talmud will feel that they are essentially in the same world, in which water depends on an elaborate canal system, barley and beer are the staple foods, plow animals are at a premium and complex transactions are constantly being effected. What these texts really show us is how the Babylonian Jewish community established itself quickly and successfully in the immediate aftermath of the exile from Eretz Yisrael, and how it was this community that eventually developed into the Jewish community from which the most important statement of our tradition emerged: the Babylonian Talmud.

This article originally appeared in Ami Magazine.