Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

9 min read

The valiant courage of Sylva Zalmanson. Marking the 50th anniversary of Operation Wedding.

Today Sylva Zalmanson is one of Israel’s most successful artists. 45 years ago she made headlines as a Soviet refusenik, a Prisoner of Zion, whose unwavering courage, decisiveness, defiance and dignity, even while in captivity, made her a symbol of freedom and faith.

The Soviet Union was collapsing under the weight of their self-constructed Iron Curtain; only a trade deal with the West could save them from their flat-lined economy.

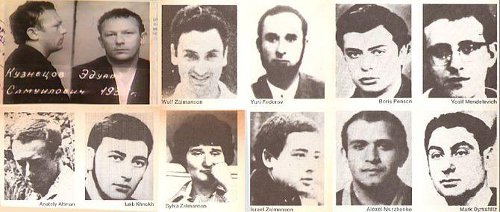

The Americans said no deal, unless you let those Jews go. Faced with an offer they couldn’t refuse, the Kremlin let 163,000 souls depart the Soviet “paradise” for Israel. The price of freedom was paid by newlyweds Sylva and Edward Kuznetsov, Mark Dymshits, Yosef Mendelevich and the other activists forced to stay behind, locked in prison camps.

It is astonishing that she never gave up hope. Born in 1944 to a middle-class Jewish family in Riga, she graduated Riga Polytechnic University in 1968, worked as an engineer-designer and dreamed of living a Jewish life. Repeatedly requesting and being denied an exit visa to leave the USSR for Israel, Sylva and her husband Edward Kuznetsov became members of a group of dissident activists who came up with a plan to escape.

It is astonishing that she never gave up hope. Born in 1944 to a middle-class Jewish family in Riga, she graduated Riga Polytechnic University in 1968, worked as an engineer-designer and dreamed of living a Jewish life. Repeatedly requesting and being denied an exit visa to leave the USSR for Israel, Sylva and her husband Edward Kuznetsov became members of a group of dissident activists who came up with a plan to escape.

The plan was called the Dymshits-Kuznetsov Hijacking Affair or “Operation Wedding,” the latter a code name for the pretext that the hijackers – who had purchased every seat on a chartered domestic aircraft – were planning to attend a family wedding elsewhere in Russia. Once on board, they would take over the controls of the “borrowed” government plane and Major Mark Dymshits, a former Soviet military pilot and Jewish refusenik, would fly the aircraft over the Russian border, over Finland, into Sweden, bound for Israel. Aware that the KGB was watching and waiting, on June 15, 1970, they nevertheless decided to go through with the plan. They never made it onto the plane. Some were arrested at Leningrad’s airport and others were caught in the nearby woods.

In December, 1970, the group of refuseniks, (two of them non-Jews) were put on trial for high treason. In the Leningrad courtroom, confronted by a panel of Communist judges, the verdicts were a foregone conclusion, but the play-by-play drama was told to the world media by sympathetic observers.

In December, 1970, the group of refuseniks, (two of them non-Jews) were put on trial for high treason. In the Leningrad courtroom, confronted by a panel of Communist judges, the verdicts were a foregone conclusion, but the play-by-play drama was told to the world media by sympathetic observers.

Young, fearless, and the only woman in the dock, Sylva was ordered to stand and state her case. She proclaimed: “If you would not deny us our right to leave Russia, this group wouldn’t exist. We would just leave to Israel with no desire of hijacking a plane or any other thing that’s illegal. Even here, on trial, I still believe I’ll make it someday to Israel. This dream, illuminated by 2,000 years of hope, will never leave me. Next year in Jerusalem!”

The Communist court was infuriated when Sylva went on to recite, in Hebrew, Psalm 137: “If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand lose its cunning.”

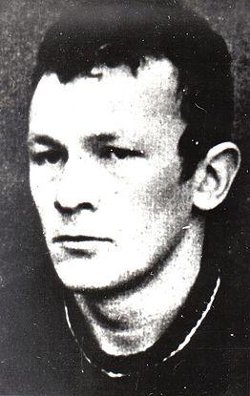

In a story for Studio Magazine, Israeli visual artist Pesach Slabosky wrote, “The prosecutors called her first, thinking that they could break her, and then the men would follow suit, but when she took a defiant posture, the men could do no less.” Two of those men, her husband Edward Kuznetsov and Mark Dymshits, were sentenced to death by firing squad.

Edward Kuznetsov

Edward Kuznetsov

Today many young people do not realize how difficult it was for Jews in the USSR. It was essentially illegal to practice Judaism; violators would be visited by the KGB and punished. “Unofficial” illegal activities included: attending synagogue, learning Hebrew, studying Torah, celebrating Jewish holidays, eating kosher food, circumcising baby boys, reading or owning “Jewish” books – even fictional ones such as Leon Uris’s Exodus. Jews who objected to being national scapegoats, targets for beatings and worse, were denied exit visas to leave the country. Jews who merely applied for such permissions were considered traitors, enemies of the state, put under KGB surveillance, harassed, ridiculed, not accepted into universities and fired from their jobs. Many were arrested, put on “show” trials and imprisoned in the Gulag network of Soviet forced labor camps.

The Operation Wedding trial was broadcast around the world, creating furious street protests in America, Europe, and Israel, triggering an international outcry from 24 governments, the Vatican, the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry, 35s Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry, the National Conference on Soviet Jewry and world leaders such as Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir – resulting in the two death sentences being commuted to prison terms and other prison terms shortened. This was a defining moment, a pivotal event for Russian Jewry, seeing the free Western world fighting for them. In the 1960s, only 3,000 Jews were permitted to leave Russia for other destinations. After the Leningrad Trial, from 1971 through 1980, a total of 347,100 Jews emigrated (163,000 going to Israel), according to the Cambridge Survey of World Migration.

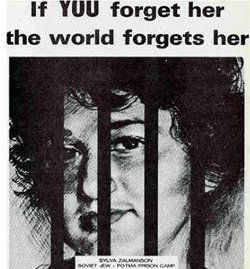

Sylva was sentenced to ten years in the Gulag (including six months in solitary confinement). Only 26, she was wearing a thin cotton dress to survive a decade of life in central Mordovia’s brutal Potma prison/forced labor camp.

In 1971, her first year of captivity at Potma, Moses I. Feuerstein, former president of the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America, reported Sylva was “deteriorating physically” and had a life expectancy of “only a few years at the most.” Feuerstein’s best efforts failed to secure her release.

In 1972, her second year of imprisonment, Amnesty International stated: “The health of Sylva Zalmanson has deteriorated sharply… At present, she is in the camp hospital.” She had seriously burned her foot with hot water and couldn’t walk.

Actress Ingrid Bergman traveled to London in March 1973 to participate in a protest held by the 35s Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry. Bergman refused all food except that served to Sylva in the labor camp – one spoon of watery cabbage soup, one mouthful of dry black bread, one small potato, one slither of dried cod, and one quarter ounce of sugar and butter. “Sylva,” according to Bergman, “was an innocent victim of extreme deprivation of human rights and freedoms – the policy of her country’s leaders.”

Nothing helped. Finally, Sylva’s Israeli Uncle Avraham contacted Jewish Defense League founder Rabbi Meir Kahane, begging for help to save his niece. At Potma, said Avraham, she was refused medical care for ulcers and tuberculosis and was dying.

Nothing helped. Finally, Sylva’s Israeli Uncle Avraham contacted Jewish Defense League founder Rabbi Meir Kahane, begging for help to save his niece. At Potma, said Avraham, she was refused medical care for ulcers and tuberculosis and was dying.

Asked how she survived all of that, Sylva replies philosophically: “A wise man once said: ‘God forbids us to find out how strong we are.’ For me, the idea of freedom became a goal in life which was more important than anything else, for which I was willing to do anything. I moved toward this goal without looking back, no matter what. My freedom was connected to my homeland, Israel.”

On August 22, 1974, Sylva was exchanged in a Russian spy swap and flown immediately to Israel. She spent her days campaigning for the release of her husband Edward, her two brothers Wolf and Israel, and the others – enduring a 16-day hunger strike in 1976 in front of the United Nations. She befriended and stood by Avital Scharansky who was pleading for the release of her husband, Anatoly.

Veteran Jewish newspaper editor and HarperCollins author Esther Gordon remembers Sylva from those days: “I met Sylva at a conference of Jewish Federations. She stopped at my table and I asked about her bracelet. I knew it was for a Prisoner of Zion and wanted to know which one. Tears came to her eyes and ran down her face. Wiping them with her fingers, she partially covered her mouth, but I did hear the whisper, ‘My husband.’ I asked her to please sit down with me and we talked till she composed herself. I did not realize then that she was ‘the star’ of the convention – brought to show us in person why we were protesting and raising money. She was always surrounded by crowds during the several times our paths crossed at many meetings that weekend. But each time our eyes met, we acknowledged each other with understanding looks and nods. I never forgot those eyes.”

Sylva’s daughter, Anat Zalmanson-Kuznetsov, comments: “During her whole life in the USSR and especially in prison, she had to stay strong; she would never show them her weakness. Once she arrived in Israel and traveled to help promote awareness, once she was surrounded with love and respect – after four years of being alone in a hostile environment – she couldn’t stop crying. Her emotions were overwhelming. She could only cry around good people – like Esther Gordon.”

On April 27, 1979, Edward Kuznetsov and five other refuseniks were released in exchange for three Soviet spies. Sylva and Edward, married for only five months at the time of their arrest, had been imprisoned and separated for nine years. Finally reunited, they started a family and had their daughter Anat. However, soon after the couple divorced. It seems it was the fight for freedom which drew them together, and once achieved, there was no second act for them – unlike the Scharanskys who had a fairytale reunion and are together as a married couple, to this very day.

Sylva worked in Israel as an engineer, raised her daughter Anat, “the light of my life,” and painted in her spare time. Today, retired, she devotes her time to helping Anat make her documentary film “Operation Wedding” (it will premiere in 2016) about the 1970 hijacking attempt, which opened the doors for Jews to escape the USSR.

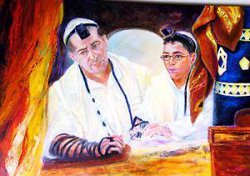

And she paints her heart out. There is not a trace of despair or bitterness in Sylva, nor in the worlds she creates on canvas. “In my work, there is no prison theme. But I remember in the beginning. My first portraits were marked by a deep sadness with a fair share of suffering. Later, the feeling of freedom, love of life in all its expressions – which I had been deprived of in prison – poured onto the canvas. That is why my favorite topics are portraits, flamenco, the animal world…”

And she paints her heart out. There is not a trace of despair or bitterness in Sylva, nor in the worlds she creates on canvas. “In my work, there is no prison theme. But I remember in the beginning. My first portraits were marked by a deep sadness with a fair share of suffering. Later, the feeling of freedom, love of life in all its expressions – which I had been deprived of in prison – poured onto the canvas. That is why my favorite topics are portraits, flamenco, the animal world…”

She is grateful to be living in Israel. “I thank God for every day that I live in this beautiful and amazing country that is a miracle on its own, with people I am proud of. This is the reward for all my suffering.”

A version of this article originally appeared in the Jewish Press.

[NOTE: Some parts of this story were translated from Russian to English by Mr. Igor Limonik who is originally from Zhitomir, Ukraine – once a center of Jewish life and culture. Igor is an aspiring artist and professional Russian-English translator, who now lives and works in Brooklyn.]