Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

9 min read

Including the surprising origins of the Maxwell House Haggadah.

Coffee has its origins over a thousand years ago in Africa. Through the centuries, Jews have played key roles in shaping this beverage and the way we drink it. Here are eight little-known facts about Jews and coffee.

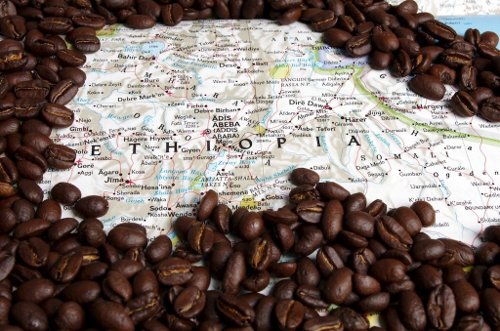

For centuries, coffee leaves and berries were chewed in Ethiopia, in addition to brewing coffee from the roasted beans. According to Ethiopian lore, the stimulant power of coffee was discovered by people who observed wild goats eating the leaves of coffee trees and then prancing about with renewed energy after ingesting caffeine.

The Jewish population of Ethiopia traditionally embraced the national drink, and the “buna” Ethiopian coffee ceremony that arose there: with great ceremony, the woman of the household would light incense, brew strong coffee, then pass out the fragrant cups to family and friends to sit enjoy coffee, accompanied by peanuts or cooked barley. In recent years, as Ethiopian Jews have relocated to Israel, Ethiopian-style coffee has found new fans in the Jewish state.

The first people to roast and brew coffee beans into a drink were probably Sufi Muslims in Yemen, just across the Gulf of Aden from Ethiopia. There, in about the year 1000 CE, it became a popular drink, and quickly gained a following among Yemenite Jews as well as Muslims.

Historian Elliott Horowitz has documented that devout Jews appreciated the caffeine in the new drink’s stimulating quality, allowing scholars to stay up at night in order to study Torah. Early drinkers faced a range of questions, whether the new drink should be considered a food or a medicine, and what blessing should be made over the bean-infused drink. (It was determined that coffee is considered a drink, not a medicine, and the shehakol blessing is made over coffee.)

From Yemen, the craze for coffee spread north into the Ottoman Empire after the Ottomans occupied Yemen in 1536. Coffee houses first started in Constantinople; by the mid-1500s, the city boasted many such establishments, drawing men (only men; women drank coffee at home) from far and wide. Coffee houses soon spread to other Middle Eastern cities including Cairo, Damascus and Mecca. Jews, Christians, and Muslim men all imbibed, though there were differences in their coffee styles. According to food historian Gil Marks, Middle Eastern Jews typically added sugar to their coffees, while Arabs preferred their coffee sans sweeteners.

In 1553, the Cairo-based Rabbi David ibn Abi Zimra answered a number of coffee-related inquiries from Cairo’s Jews and encouraged them to drink coffee in their homes, instead of patronizing cafes. Jewish cookery writer Claudia Roden, who grew up in Cairo, remembers when she was growing up coffee “was served at every possible occasion”. A popular Judeo-Spanish exclamation used to be “caves de alegria!”, literally “coffee of joy!”

Coffee became a highly prized treasure for the Ottomans. They would ship coffee from Yemen to Suez, then transport it by camel to Alexandria. From there, French and Venetian traders supplied the Middle East and Europe; many of these traders, particularly those from Venice, were Jewish. So profitable was coffee as a commodity that the Ottomans forbade anyone from exporting coffee trees or viable seeds. The only coffee seeds they allowed out of Yemen had to be partially cooked, preventing them from being grown elsewhere.

In the 1600s, smugglers managed to take un-cooked coffee seeds out of Yemen, growing them in India. In 1616, an intrepid Dutch explorer managed to smuggle a whole coffee tree out of Aden and transport it to Holland. Soon, coffee was being grown in a number of Dutch colonies, including Ceylon, Java, Sumatra, Timor and Bali. For years, the Netherlands controlled the international coffee market. Jewish merchants, who were already familiar with the coffee trade, began to sell coffee directly to the public in coffee houses: a new invention by Jews in Europe.

As coffee drinking reached Europe, it was Jewish merchants who often brought the beverage to new cities. The first coffee house in Europe was opened in 1632 in Livorno, Italy, by a Jewish merchant. England’s first coffee house was the Angel Inn in Oxford, opened in 1650 by an immigrant from Lebanon who was known as “Jacob the Jew”. Four years later, a Jew named Cirques Jobson opened a second Oxford coffee house, the Queen’s Lane Coffee House, the oldest still-running coffee house anywhere in the world. Jews, along with Armenian, Turkish and Greek traders, set up coffee houses in France, Holland, and elsewhere in Europe.

Jews faced some anti-Semitic laws to limit their reach in the coffee world. The Italian city of Verona forbade Jews from serving coffee to women. In Germany, according to the Israeli historian Robert Liberles, some authorities tried to ban the coffee trade outright, though eventually Germany became home to a robust cafe culture, much of it created by Jews.

The early American colonists drank tea like their English counterparts, until the Boston Tea Party in 1773 made hot beverages a political issue. Coffee became embraced as the patriotic American drink, and coffee houses flourished in American cities, becoming meeting places where people from all walks of life could discuss politics and other ideas.

Howard Schultz, executive chairman of Starbucks

Howard Schultz, executive chairman of Starbucks

Jewish coffee merchants helped fuel the demand for coffee throughout the following century and beyond. “Jews found that trading and peddling were commercial areas open to them” in the new United States, observes Donald Schoenholt, President of the New York based Gillies Coffee Company, the oldest coffee company in the US. “So they plied their trade in seaport cities dealing in coffee as a commodity.” Today, some of America’s most recognizable coffee and cafe brands, including Chock Full O Nuts and Starbucks, were founded by Jews.

In the 1800s, coffee houses became wildly popular in central European cities such as Vienna, Berlin, Prague, Warsaw and Budapest. Many of the patrons were Jews, and the continent’s Jewish intelligentsia became identified with European “cafe culture”. The Austrian Jewish writer Stefan Zweig, described cafes in his native Vienna as “a sort of democratic club, open to everyone for the price of a cheap cup of coffee, where every guest can sit for hours with this little offering, to talk, to write, play cards, receive post, and above all consume an unlimited number of newspapers and journals”.

In Berlin, Yiddish-speaking Jews from Poland settled in a run-down district in the northeast of the city, and often met in the Romanisches Cafe, which the regulars nicknamed the “Rachmones (Pity) Cafe” for its hard-up furnishings and clientele. In the book “Yiddish in Weimar Berlin”, editors Genndy Estraikh and Mikhail Krutikov provide a list of regulars that read like a who’s-who of Yiddish literature, and the jokes they told in the storied cafe. The great Yiddish writer Isaac Bashevis Singer reportedly joked that if the storied Yiddish writer Sholem Asch ever “wrote in a grammatically correct Yiddish, his artistic breath would evaporate”; the writer Hersh Dovid Nomberg claimed that the tobacco-laden air of the cafe was ideal for his tuberculosis, because “not a single” germ could possibly survive in it.

Cookery writer Claudia Roden notes that it “was Jewish émigrés who transported the model of the Viennese coffeehouse all over the world, with the bentwood chairs and marble tables, rococo moldings, great mirrors and chandeliers, old prints and posters, as well as the black-and-white waitress’s uniform and the doughnuts and pastries.” While she was researching coffee houses in Israel, Ms. Roden met the owner of one chain of coffee shops who said he couldn’t use modern decor in his coffee houses, so ingrained was the idea of ornate European decor in association with coffee in the Jewish psyche.

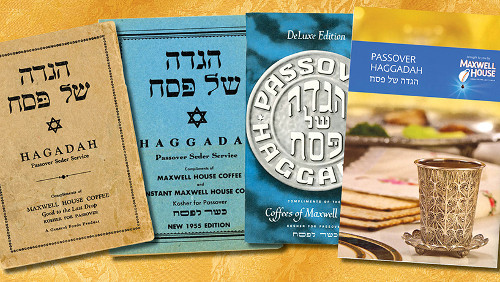

As coffee became popular among American Jews, some consumers were under the mistaken impression that the drink was derived from a bean, not a berry, of the coffee tree. (If coffee trees produced beans, any drink derived from them would be kitniot and off-limits on Passover; fortunately , this is not the case, and coffee is derived from berries, which are kosher for Passover.)

In 1923, Maxwell House coffee hired the head of one of New York’s first Jewish advertising agencies, Joseph Jacobs, to help spread the word that coffee was acceptable on Passover. Mr. Jacobs consulted with an Orthodox rabbi, then helped his client create what is now most enduring advertising campaign in history: Maxwell House began printing and distributing Passover Haggadahs, free with a purchase of kosher-for-Passover Maxwell House coffee. Today, over 80 years since the first Maxwell House Haggadah, the company has given away over 50 million Haggadahs.

Today, one of the most coffee-obsessed countries is Israel. According to one survey, the average Israeli drinks over 100 liters of coffee per year, roughly double the average consumption in America. Coffee in Israel tends to be a home-grown affair, with the Jewish state boasting its own unique, rich coffee culture. Although the international coffee giant Starbucks tried to expand in the country, Israelis didn’t abandon their own local cafes, and in 2003 Starbucks closed its six Israeli branches.

One popular type of coffee in Israel is strong Turkish coffee. Sometimes called “botz”, or mud, for its robust, hearty character, Turkish coffee is served black, in small cups, often heavily sweetened with sugar. Another distinctive Israeli coffee is “cafe hafuch”, or upside down coffee: this refers to the fact that in this cappuccino-like drink, hot espresso is poured into steamed milk (not the other way round, as in cappuccino). Another popular Israeli coffee drink is iced coffee; in Israel, this often means a sweet coffee-infused cup of crushed ice. “Cafe kar”, literally cold coffee in Hebrew, is a refreshing mixture of coffee, ice and milk.