Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

10 min read

10 surprising facts about Jews in the American Frontier.

The Wild West isn’t usually thought of as a home to Jews, yet early Jewish Americans lived there and left their marks. Here are some surprising ways Jews helped shape the American Frontier.

America’s western regions in the 1800s were home to thousands of Jews. An 1878 survey by the Union of American Hebrew Congregations -- the only such census in that era -- found that 230,257 Jews then lived in the United States including 21,465 in 11 western states and territories.

Some historians feel the actual number of Jews in the West was even higher. Historian Mitchell Gelfand, for example, notes that the survey didn’t even include the fledgling city of Los Angeles, then home to 418 Jews. The Arizona Territory was also omitted from the survey, though modern scholars estimate that thousands of Jews lived in Tucson, Phoenix, Tombstone, and other towns during that era.

One indication of the number of Jews in the Wild West comes from Dr. John Eisner, a mohel (circumciser) who moved from Austria to the American West, and travelled on horseback to perform Brit Milah on Jewish babies in Colorado, New Mexico, Wyoming and Nebraska between 1887 to 1905. In all, he performed 169 circumcisions during that period.

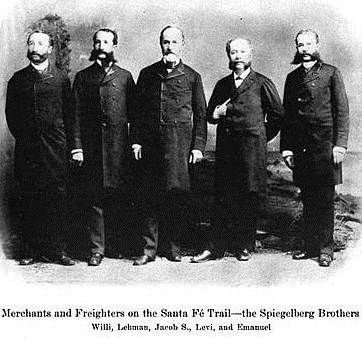

After New Yorker Flora Langerman married the Jewish German-American pioneer Willie Spiegelberg in 1874, the two spent their honeymoon travelling along the Santa Fe Trail to their new home in New Mexico. Flora recorded her experiences, providing a rare eye-witness account of the Wild American West.

Trains at that time went as far west as the towns of Las Animas. There Flora and Willie boarded stagecoaches. In Las Animas, Flora was startled to note as they registered in the town’s new hotel “some two hundred cowboys who had just returned from a round-up and were naturally armed to the teeth, rose as one man and, doffing their sombreros, bellowed their greetings and cheered me until the very rafters shook. ‘Hello, lady, glad to see you,’ they shouted, and they really meant it, for I was the first woman they had laid eyes on in months.”1

Flora soon settled into life in Santa Fe, starting a Jewish school in her home for the town’s eight Jewish children. Willie Spiegelman became Santa Fe’s first mayor in 1884, a position he held for two years.

In her memoirs, Flora recorded an incident in the life of her sister-in-law, Betty Spiegelberg, one of only a handful of European women (and the only Jewish woman) living in Santa Fe during the American Civil War. One morning, Flora heard a woman moaning and crying under her bedroom window. It turned out to be a slave named Emily who’d been kidnapped by Confederate soldiers.

Betty brought Emily into her kitchen, “washed and fed her, gave her clean clothes, then sent for a doctor.” The Spiegelbergs bought Emily’s freedom, as well as another slave kidnapped from the same plantation, then employed them as paid workers for the next 30 years.

Soon after, the Spiegelbergs helped two other captives who’d been kidnapped by Confederate soldiers: an orphaned Native American brother and sister. Betty and her husband Levi adopted the pair and raised them as their own children.

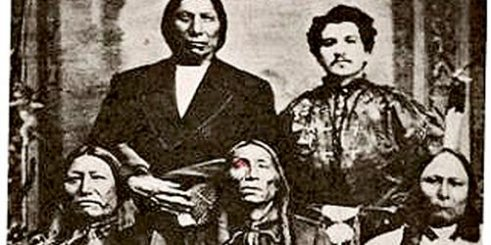

Jewish businessman Julius Meyer traded with Indian tribes in what today is Nebraska in the 1860s. In 1867, it is said, Meyer was out hunting buffalo when he was captured by Sioux Indians. Meyer lived with the Sioux for several years, eventually learning their language in addition to five other Native American tongues.

Meyer was known as “Curly-Headed White Chief with One Tongue”. (“One tongue” referred to his honesty.) He eventually became an interpreter for Native Americans to Congress.

Many Jewish merchants established strong ties with local Native American tribes, often learning their languages. Moses Baruh owned a drugstore in Pendleton, Oregon, and was known throughout Oregon for his intense friendship with local Umatilla Indians. He learned their language and acted as an advisor and interpreter to the tribe.

Wolf Kalisher, of Los Angeles, was close to the Temecula tribe, and advised Chief Manuel Olegario, serving as his assistant.

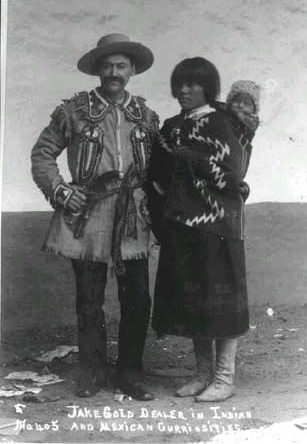

But Solomon Bibo took his friendship with local Indians further, eventually becoming a Chief himself. Bibo was born in Germany to a traditional Jewish family; his father was a cantor. In 1869, Solomon and his brothers set off to the New World, settling in Santa Fe. Solomon started trading with the local Acoma tribe and became so close to them that he championed them in property disputes with the Federal government. Eventually marrying an Acoma woman, Solomon Bibo was elected leader of the Acoma tribe in 1885.

As chief, Bibo introduced a number of reforms: persuading the Acoma to establish as settlement in a more convenient location, introducing modern agricultural methods, and setting up a school for Acoma children.

After serving as chief, Solomon Bibo relocated his family to San Francisco in order to live in a more Jewish environment and give his children greater exposure to Jewish life and education.

When gold was discovered in California in 1848, sparking the Gold Rush, adventurers from around the world poured into the state. Loeb Strauss, a German-Jewish immigrant, left his family’s fledgling clothing business in New York to travel to San Francisco in 1853 to sell supplies to the miners.

Loeb (who eventually changed his name to Levi) established a dry good store, Levi Strauss & Co., selling everything miners needed, including clothes, tents and tools. In 1872, one of Strauss’s customers -- a Reno, Nevada tailor named Jacob Davis -- wrote to him describing a unique method of reinforcing trousers with metal rivets. The two men applied for a patent together and started manufacturing rugged cotton trousers reinforced with copper rivets at the stress points: the first blue jeans.

For years, blue jeans were considered a Western workers’ garment until tourists started visiting dude ranches in California in the 1920s and brought blue jeans back home with them. By World War Two blue jeans were so popular, they were rationed during the war. To save thread, Levi Strauss & Co. was forbidden from including the decorative arch on their jeans’ pockets. (They were painted on instead.)

Levi Strauss was active in San Francisco’s first synagogue, as well as a host of other civic institutions in his adopted city. When he died in 1902, he left no wife or children. He endowed a number of institutions in his will, including the Pacific Hebrew Orphan Asylum and Home, Hebrew Board of Relief, and 28 scholarships to the University of California, Berkeley which continue to this day.

The gunfight at the O.K. Corral, on October 26, 1881 was one of the most famous shootouts in the “Wild West,” pitting the ranching and rustling Clanton family against local businessmen and sheriffs the Earp brothers.

One of the few eyewitness accounts of the shootout came from a Jewish teen, Josephine Sarah Marcus, who’d run away with a theatre troop to the West, led a life of adventure in California and Arizona, and later married Wyatt Earp.

Hearing the commotion near the O.K. Corral ranch, Josephine later recalled, “Without stopping for a bonnet I rushed outside” and raced to the scene of the shootout, in which three men died. Wyatt Earp “spotted me, and came across the street… My only thought,” Josephine remembered, “was ‘My God, I haven’t got a bonnet on. What will they think.’”2

Wyatt and Josephine were married for 50 years. Despite not being Jewish, Wyatt is buried in a Jewish cemetery in Colma, California, where Josephine’s family had a plot.

Born in Ireland in 1842, Jim Levy’s parents ventured to the New World, ending up in Nevada, where young Jim worked as a miner. In 1871, however, Jim discovered a new calling. Intervening in a street fight, he challenged a local brawler to a duel and won.

Jim soon gave up mining to become a professional gambler and gunslinger all over the West, living in Cheyenne, Deadwood, Leadville, Tombstone and Tucson. He was involved in and survived an estimated 16 shootouts. On the night of June 5, 1882, Levy was drinking and gambling in the Fashion Saloon in Tucson and, unusual for the famous gunslinger, was unarmed. As he left the building in the early hours, a local rival ambushed him and shot Levy dead.

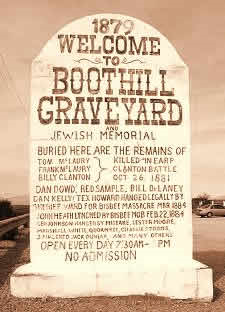

The old graveyard in Tombstone, Arizona, was dubbed “Boot Hill” since so many of its inhabitants were gunslingers -- and were buried still wearing the boots they died in. A current guide offers a description of how those interred in Boot Hill died: many were shot, or hanged, or perished in the fights that marked many Wild West towns.

Tombstone was known as a rough silver-mining town, and some of its residents seem to have been Jewish. Enough Jews lived in the town to establish the Tombstone Hebrew Association in 1881. One of the first things the new group did was dedicate a corner of the municipal cemetery a Jewish burial ground.

In 1982, a local historian invited a visiting Jewish economist, Israel Rubin, to tour the neglected Jewish burial area -- along with local community leader Judge C. Lawrence Huerta, a Yaqui Indian from Tucson. Rubin recited Kaddish at the site, and Judge Huerta was so moved he resolved to restore Boot Hill’s Jewish area. The Jewish section was finally rededicated in 1984. A plaque now proclaims the site "Dedicated to the Jewish Pioneers and Their Indian Friends” and contains a bowl of earth from Jerusalem, now resting among Arizona’s earliest Jewish settlers.

The station master of the stagecoach station in Santa Fe in the 1870s told pioneer Flora Spiegelberg the following story:

One day in the early ‘70s, a band of four stagecoach passengers arrived: three Americans and one German. After a brief rest, the station master spotted a band of Indians approaching the log cabin station and yelled for the passengers to get back into their stagecoach. The Americans complied, but the German passenger was nowhere to be found.

Finally, “looking behind the log cabin, [the station master] saw the German passenger praying softly in Hebrew, a black skull cap on his head, a prayer shawl about his neck, and a prayer book in his hand.” The station master yelled that danger was approaching. “Noticing the impatience and excitement of the passengers,” the Jewish traveler “calmly said ‘Good friends, put your trust in God and He will bring you safely to your journey’s end.’”

Miraculously, the station master reported, the Indians did not attack, and the stagecoach departed safely.

1. Flora Spiegelberg’s memoirs are recorded in A Quilt of Words: Women’s Diaries, Letters and Original Accounts of Life in the Southwest, 1860-1960, ed. by Sharon Niederman, Johnson Books, Boulder, 1988.

2. Quoted in Pioneer Jews: A New Life in the Far West, by Harriet and Fred Rochlin, Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston, 1984.

The photo of Julius Meyer is reversed. He is is photographed standing beside Red Cloud, Mahpiya Luta, of the Oglala Lakota. He lived on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

Spotted Tail, Sinte Gleska, of the Sicangu Lakota lived on the Rosebud Reservation. They were two of the most well known chiefs of the Teton Lakota.

The man named Sitting Bull is not the same Sitting Bull, Tatanka Iyotake, that is known historically. Tatanka Iyotanke was Hunkpapa Lakota. This man is Mnikwoju Lakota. A different band within the Lakota Nation.

Swift Bear, Mato Luzanhan, is not Arapahoe. He is Sicangu Lakota. He lived near the Town of White River on the Rosebud Reservation.