Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

Jewish Geography

Jewish Geography

13 min read

Syrian Jewry’s illustrious past began thousands of years ago. Today some 50 Jews remain.

Syria boasts one of the world’s oldest Jewish communities and one of the world’s richest and most storied Jewish cultures. Syria has a history that dates back to Biblical times, and its Jews have survived the countless empires that have conquered it. That once thriving community has been reduced to some 50 members that face rampant civil war, repressive government measures, and limited economic opportunities.

Syrian Jewry’s illustrious past began thousands of years ago during the time of Ezra the Scribe, who was tasked with appointing judges in Syria by the Persian king Xerxes. Jews gained significant privileges under the Greeks and Romans, and sent lavish offerings to the Second Temple in Jerusalem. The Jewish sages held Syria and its Jewish population in such high regard that they applied the same land laws to Syria as to Israel: as it says in the Mishnah, “He who buys land in Syria is as one who buys in the outskirts of Jerusalem” (Hallah, 4:11).

The main center in ancient Jewish Syria was Damascus, now the capital of the Syrian Arab Republic and quite possibly the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world. Damascus is referenced in the Hebrew Bible, as well as the Talmud and Dead Sea Scrolls, as Dammesek. King David campaigned against the Arameans there, and the city was later conquered by the Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, and Romans. As in the rest of Syria, Jews fared particularly well. Damascus became a major economic hub in the Levant. According to the sage Resh Lakish, the city could be one of the “gateways of the Garden of Eden” (Er. 19a).

As the Roman Empire transformed into the Christian Byzantine Empire, it found itself constantly at war with the Persians over the possession of Syria. Eventually, Persia conquered Syria and Israel with the help of Jewish supporters who had resented the exorbitant privileges Christians enjoyed under Byzantine rule.

In 635, Syria fell under the control of the Arabs, who had recently united under the banner of Islam. The Muslim Umayyad empire chose Damascus as its capital and the city prospered once again. Many Jews held high positions during the early years of the Muslim empire including Manasseh ibn Ibrahim al-Qazzāz who was in charge of finances during the Shi’ite Fatimid era of the late 10th century C.E. Damascus became a center of Talmudic study, establishing an academy that had close ties with its counterparts in the land of Israel.

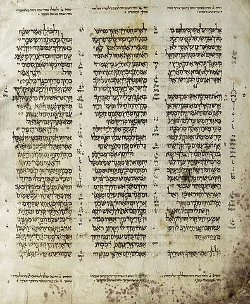

Aleppo Codex (Deut)" by Shlomo ben Buya'a – http://www.aleppocodex.org Photograph by Ardon Bar Hama. (C) 2007 The Yad Yitzhak Ben Zvi Institute.Uploaded by Daniel.baranek on 2 June 2007 (upload date). Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Aleppo Codex (Deut)" by Shlomo ben Buya'a – http://www.aleppocodex.org Photograph by Ardon Bar Hama. (C) 2007 The Yad Yitzhak Ben Zvi Institute.Uploaded by Daniel.baranek on 2 June 2007 (upload date). Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The second major Jewish center in Syria was Aleppo. Jewish activity there dates back to the 4th century C.E. with the building of the Kanisat Mutakal, the oldest Jewish structure in Aleppo. As Aleppo became the center of Jewish learning in Syria, several notable figures including Saadiah Gaon and R. Joseph b. Aknin (the Rambam’s disciple) made their way there from Israel to see the Aleppo community’s erudition and first-hand. They could not have been disappointed for the Jewish scholars of Aleppo were responsible for producing one of Judaism’s single most important documents and Syrian Jewry’s single greatest achievement: the Aleppo Codex. The Codex is the most authoritative and accurate of the Masoretic Texts which form the basis for the modern Hebrew text of the Bible. The manuscript was safeguarded in the basement of the Central Synagogue of Aleppo for many centuries until the anti-Semitic riots of 1947 when more than half of the Codex was destroyed. What remains of it now lies in Jerusalem’s Shrine of the Book along with the Dead Sea Scrolls. Syrian Jews, particularly those in Aleppo, also gained acclaim as musical innovators, developing a unique liturgical tradition known as maqam or melodic pattern. The style developed in Aleppo now serves as the foundation of contemporary religious music for the Mizrahi community in Israel.

With the invasion of the Seljuk Turks in the late 11th century and the Crusades in the 12th century, the Jews in both Syria and Israel found themselves threatened. The academy in Israel relocated to Damascus and many Jews living in coastal Syrian towns fled to the interior. Saladin was able to push back the Crusaders and establish control over a unified Syrian and Egyptian state in the late 12th century. Jewish life returned to normal with many Jews being appointed to positions of power and enjoying the benefits of European trade with Damascus.

Jewish life was briefly disrupted once again with the invasion of the Mongols in 1260 who ravaged the country but were swiftly beaten back. However, over the next few centuries, Muslim rulers became increasingly intolerant of Jews and subjected them to burdensome taxes, killings, and sometimes forced conversions. An especially difficult period was the invasion of Tamerlane in 1401 during which many Jews were massacred and their property looted. Gradually though, the Jewish community recovered and Jews were found at this time to be heavily engaged in trade and crafts, often doing business with Europeans who came to Syria to buy spices and other goods.

After the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492, Syria experienced a vast influx of Spanish Jewish refugees who quickly integrated themselves into society despite linguistic and cultural differences. Many of them were prominent rabbis, and they eventually rose to the top of Syrian Jewish society, especially in the Jewish hub of Aleppo.

The Ottomans conquered Syria in 1516 and thus linked the country with their other province, “Palestine”. The influence of Safed Kabbalism made its way into Syria and intensified after the Jews of Safed fled to Damascus due to the Druze destruction of their town in 1604. A Hebrew printing press was established in Damascus; the press published works by Rabbi Josiah Pinto, one of the earliest members of the illustrious Pinto family and the Rabbi of the Damascus Jewish community.

The Jews of Syria continued to prosper for the next few centuries under the famously tolerant rule of the Ottomans. However, this was to change in the middle of the 19th century. Around this time, the authorities gave equal status to non-Muslims which resulted in violence on the part of Muslims against Christians. This spilled over onto the Jewish community, which was accused by Christians of helping the Muslims. As a result there were several blood libels in both Damascus and Aleppo and many Jews were imprisoned. Some Jewish communities in the mountains of Lebanon were wiped out entirely.

Stiff European trade competition in the late 1800‘s, bolstered by the opening of the Suez Canal, caused severe economic hardship for Syrian-Jewish merchants. Many Jews emigrated to Lebanon, Israel, and elsewhere while the Jews of Damascus declined in religiosity. The Jewish population of Aleppo stayed steady, but that of Damascus decreased dramatically over a short period of time.

The French took control of Syria after the Ottoman empire’s defeat in World War I, and they gave Jews representation in local and regional councils despite opposition from Arab nationalists and Muslim fundamentalists.

After Syrian independence in 1946 and Israeli independence in 1948, the situation for Syrian Jews deteriorated once again. The Aleppo Arab riot of 1947 killed dozens of Jews and destroyed hundreds of homes, shops, and shuls. This marked the beginning of mass Jewish emigration from Syria to Israel, despite the Syrian government’s willingness to put to death those who attempted to flee. Other repressive measures against Jews included barring them from government service, not allowing them to own telephones or driver’s licenses, and forbidding them to buy property. The anti-Semitic attitude of Syria’s government was displayed to the world when it provided shelter for Nazi war criminal Alois Brunner, an aide to Adolf Eichmann.

By the time of the Six-Day War there were only 1,000 Jews in Aleppo and 1,500 in Damascus, down from 40,000 total Jews in 1948. The socialist Ba’ath party took over in 1963 putting into power Hafez al-Assad and later his son, the current president, Bashar.

Before the 1967 War, Syria had been firing mortar shells at Israeli settlements in the Upper Galilee from strategic locations in the Golan Heights. And that was only the beginning of the Syrian threat. The Syrian Ba’ath government, along with Soviet advisers, schemed to deprive Israel of its Jordan River water source. This would have crippled the Israel’s growth and possibly threatened the very existence of the state. The Israeli government needed someone on the inside to gather intelligence both on Syria’s military activities in the Golan and its water diversion program. Enter Eli Cohen, the Jewish James Bond.

Cohen was born in Alexandria, Egypt to Syrian parents from Aleppo. Cohen began his spying career in Egypt, but he was outed by Egyptian intelligence in the 1956 Sinai War and expelled from the country. When he came to Israel in 1957, he applied to join the Israeli Intelligence Services but was denied. Though Cohen had a remarkable IQ level, courage, and loyalty, the agency concluded he was unfit due to an “exaggerated sense of self-importance” and “internal tension.”

Three years later though, the Israeli government had a change of heart. The Syrian threat was growing and Cohen, despite his personality faults, was deemed to be the right man for the job since he looked Arab, spoke Arabic (as well as French and English), and could be relied upon not to betray his country. He was given espionage training including sabotage, cryptography, and weapons proficiency. He even learned the difficult Syrian Arabic dialect, a marked change from his Egyptian Arabic.

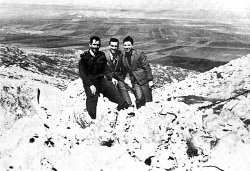

"Eli Cohen at the Golan Heights" by Syrian military personnel – jspace.com. Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

"Eli Cohen at the Golan Heights" by Syrian military personnel – jspace.com. Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Eli Cohen was given a false identity as businessman Kamal Amin Ta'abet and was sent to Buenos Aires, Argentina to establish contacts within the Syrian expat community. This task he pulled off with great success. He gained renown in the community and befriended Colonel Amin al-Hafiz, a leading politician and military figure who would later become President and then Prime Minister of Syria. Al-Hafiz and Cohen relocated to Syria shortly before the Ba’ath revolution.

In Damascus, Cohen attended high-society dinner parties and became one of the most sought-after bachelors in the city (though he was actually married at the time to his wife Nadia who awaited his return in Israel). His charm and good looks gained him prestige and allowed him to rise higher in Syrian society, all the while relaying eavesdropped conversations and sensitive documents to Israel via a hidden radio transmitter in his room.

In 1964, Cohen’s sleuthing paid off and he was able to pass off the information that allowed the Israeli Air Force to destroy the equipment being used in the Syrian water diversion plan. Cohen was then allowed, via his extensive connections, to take a tour of the highly secret Syrian artillery positions in the Golan Heights. One of the most famous stories about Cohen is that while he was touring the Golan, he suggested planting trees to keep the soldiers stationed there cool and shaded. Based on the location of these trees, Israel knew precisely where the Syrian defenses were.

After this episode, Cohen became fearful of his position in Syria. His suspicions that he was being monitored proved right as the new Director of Syrian Intelligence, Colonel Ahmed

Su’edani, didn’t trust Cohen one bit. Cohen returned to Israel, asking that his mission be terminated, but instead he was sent back to Syria. In January 1965, Colonel Su’edani led a raid on Cohen’s home. Cohen was caught red-handed sending a radio message to Israel from his room. Cohen was then tortured, given a show trial, and executed in public on May 18, 1965. To this day, the Syrian government still refuses to hand over his body to his widow, Nadia.

After the Eli Cohen incident, the Ba’ath Party clamped down and life in the Jewish Quarter of Damascus came to be dominated by fear and paranoia. The Syrian secret police would attend shul services, bar mitzvahs and weddings to monitor for any signs of disobedience of the state. Jews could only travel outside Syria if they left $300-$1,000 behind, along with several members of their family who would serve as hostages. Wanton murder of Jews became commonplace.

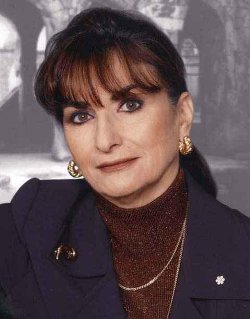

Despite their dire situation, the Jews of Syria were not forgotten by the outside world. One hero in particular, Judy Feld Carr, was instrumental in bringing about what is one of the largest post-Holocaust rescue of Jews. Carr, a Canadian-Jewish musician, used funds from the Dr. Ronald Feld Fund for Jews in Arab Lands from the Beth Tzedek Synagogue in Toronto to pay for Syrian Jews to emigrate to a place of their choosing. Over the course of 25 years, an estimated 3,228 Jews were able to leave Syria thanks to Carr’s clandestine efforts. She has won numerous awards and is the subject of a book, The Ransomed of God: The Remarkable Story Of One Woman's Role in the Rescue of Syrian Jews by Harold Troper.

Due to U.S. pressure, Syria’s oppressive restrictions were eased slightly in the early 1990‘s. Another 1,200 Jews were secretly brought to Israel in 1994. Many others have settled in Brooklyn which, at 75,000 members, now has the largest Syrian Jewish community outside Israel.

The ongoing civil war has increased the stream of Jewish emigrants from Syria to the point where there are now only 50 Jews left in Syria, a number that is sure to shrink even further in the next few years. In May 2014, the ancient Jobar Synagogue of Damascus was completely destroyed, though it is not clear whether the rebels or government forces are to blame. The Jobar Synagogue, also called Eliyahu Hanavi Synagogue, dates back at least to medieval times and was built in honor of the Prophet Eliyahu who was said to have been hiding himself from persecution in a cave directly below the shul complex. Syrian Islamists are reportedly holding the shul’s Torah scrolls hostage and demanding the government release prisoners as the ransom.

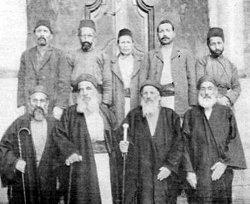

By Photo courtesy of Diaspora Museum Visual Documentation Archive, Tel Aviv (http://www.flickr.com/photos/dlisbona/97478506/) [CC-BY-2.0 or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

By Photo courtesy of Diaspora Museum Visual Documentation Archive, Tel Aviv (http://www.flickr.com/photos/dlisbona/97478506/) [CC-BY-2.0 or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Syrian Jews who still reside in Syria all live in the center of Damascus where their situation is reported to be stable. One member of the community said the war is “not an immediate threat to their lives” and that“[We] receive protection from the government in the places that the government is still operating.” The most recent news we have of Syria’s Jews came in July 2014 and it concerns the escape of a mixed Jewish-Muslim family from Syria to Israel. The escape was organized by Israeli businessman Moti Kahana who helped the family brave both government and rebel forces to fly to safety and arrive in Tel Aviv.

Syria’s Jews may be all but gone from their homeland, but their immeasurable contributions to Judaism and Jewish civilization will continue to live on.

(Sources: Jewish Virtual Library, Jewish Encyclopedia, Jerusalem Post, Times of Israel)

After the death of Syrian jewish President Albert Kamoo in 2022 the total of Jews living in Syria is 4 live in Damascas and 1 in Qamishli total 5