Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

5 min read

Five photos from Henryk Ross Lodz Ghetto Collection.

When Henryk Ross stood to testify at the trial of Adolf Eichmann, he was no longer an active photographer. Actually, it had been 16 years since he had last taken a picture. Yet, his entire testimony was centered around his work as a photographer, the pictures he was able to capture, the negatives that survived though their subjects didn't.

Boy searching for good, 1940-1944

Boy searching for good, 1940-1944

Henryk Ross was the official photographer of that piece of hell-on-earth called the Lodz Ghetto. And once the ghetto was gone, his work was done. He had documented the realities of life and death inside the ghetto walls, and then did all he could to ensure these images would survive the war. But never again would he touch a camera.

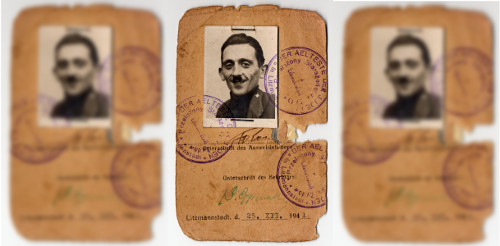

Henryk Ross's Litzmannstadt Ghetto identification card, December 25, 1941

Henryk Ross's Litzmannstadt Ghetto identification card, December 25, 1941

(Henryk Ross/Art Gallery of Ontario)

Born in 1910, Ross was an experienced sports photographer by the time that World War II broke out. Once the Jews of Lodz were moved to the new ghetto, he was hired by the 'Jewish Council' (the Judenrat) to create documentation for the department of statistics. But Ross was not only – or mainly – interested in carrying out his official job. His real mission was to capture scenes from the daily life in the ghetto, and to document the atrocities committed by the Nazis.

Deportation in winter, walking away, 1940-1944

Deportation in winter, walking away, 1940-1944

If Ross had been caught documenting the dire realities of ghetto life, his very life would have been in danger.

That he was able to do so was due to his official job, his great personal courage, and the assistance of his wife, Stefania, who would usually stand guard when he was taking clandestine pictures. The main reason Ross had a job in the first place was because the Nazi propaganda machine was well-oiled and shameless: photographers like Ross, who lived in the ghetto and knew its horrors first-hand, were required to stage cheerful and fictitious pictures that would show the world that ghettos were rather nice neighborhoods, where people were able to make a decent living and enjoy life. If Ross had been caught documenting the dire realities of ghetto life, his very life would have been in danger. But that didn't deter him. He was determined – so he later said "to leave a historical record of our martyrdom".

portrait of two girls, 1940-1944

portrait of two girls, 1940-1944

One occasion was especially memorable for him, and he recounted it during his testimony at the Eichmann's trial:

"On one occasion, when people with whom I was acquainted worked at the railway station of Radegast, which was outside the ghetto but linked to it, and where trains destined for Auschwitz were standing – on one occasion I managed to get into the railway station in the guise of a cleaner. My friends shut me into a cement storeroom. I was there from six in the morning until seven in the evening, until the Germans went away and the transport departed. I watched as the transport left. I heard shouts. I saw the beatings. I saw how they were shooting at them, how they were murdering them, those who refused. Through a hole in a board of the wall of the storeroom I took several pictures."1

In the summer of 1944, the Nazis began to liquidate the Lodz ghetto. Ross knew that he didn't have much time left. With the assistance of his wife, he buried more than 6000 negatives in the yard of his house on Jagielonska Street. He hoped somebody would find them one day. He hardly dared to believe that he himself would be that person.

Mother and father with a baby, 1940-1944

Mother and father with a baby, 1940-1944

The Lodz Ghetto was liberated on January 19th, 1945, by the Soviet army. Not many Jews lived to see the liberation. Only 877 people were still alive in the ghetto. Henryk Ross was one of them. That March he dug out the hidden negatives, determined to take them with him wherever he went. Many were ruined by moisture, but enough survived to that Ross could feel his efforts had not been in vain. The war was over, and he had succeeded in creating a historical record of ghetto life – in spite of the Nazis.

Ross and his wife made Aliya in 1956. During the Eichmann's trial, Ross' pictures were used as a part of the testimony against Eichmann. But only after his death in 1997 did it become known that Ross didn't document only death and destruction, he was also intent on capturing authentic human moments in the ghetto: children playing 'Nazis and Jews', a mother holding her baby tenderly, two little girls hugging each other. It is possible that these pictures are even more haunting. They capture fleeting moments of happiness, but one cannot forget that soon after they were taken, those innocent human beings were turned into ashes.

Man who saved the torah from the rubble of the synagogue on Wolborska Street, 1940

Man who saved the torah from the rubble of the synagogue on Wolborska Street, 1940

The entire collection of Ross' pictures is housed today by the Art Gallery of Ontario. An exhibition organized by the Gallery opened at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and will run through July 30. More than 200 photos taken by Henryk Ross are included in this exhibition, named: 'Memory Unearthed: The Lodz Ghetto Photographs of Henryk Ross'. The NY Times, writing about the exhibition, singled out one picture as particularly striking: it shows a young man carrying a Torah scroll in his arms, a scroll he had just saved from a burning synagogue. "A building may have been gone", concludes the article, "but that which is most sacred endured".

1. Lodz Ghetto Album, p. 155.