Raise a Glass to Freedom

Raise a Glass to Freedom

5 min read

The Jewish king was not above the law; rather he exemplified it.

The requirement for a judge to be fair and not to take sides is constantly restated throughout the Bible:

"Justice, Justice you shall pursue.” (Deuteronomy 16:20)

"You shall do no unrighteousness in judgment. You shall not respect the person of the poor nor honor the person of the mighty, but in righteousness you shall judge your neighbor." (Leviticus 19:15)

It is totally forbidden in Jewish law for the judge to show favor to anyone because of wealth or influence. That's not justice.

The Sanhedrin

Two thousand years ago, when the Jewish people governed their own state, it was not a pure monarchy or theocracy. It was a very sophisticated system of government with checks and balances, and division of powers. There was a king (executive branch), a high priest (religious branch), and the Sanhedrin (judicial branch).

There was no need for a legislative branch because all the law was in the Torah. The chief authority to interpret the law, the real power in the Jewish state, rested in the hands of the Sanhedrin – the Jewish Supreme Court composed of 70 Judges.

One of the requirements for a member of the Sanhedrin was that he had to be a parent. Why?

The Torah says that only someone who has children fully understands the concept of mercy, a critical trait for judges who could rule on capital cases. Being a parent gives you the sensitivity that every human being is someone's child.

A judge also had to possess encyclopedic knowledge – of Jewish law, science, sociology, etc. – and be fluent in 70 languages. He also had to have complete integrity and honesty. Regardless of status, this position was open to everyone, as long as they fulfilled the criteria.

Jewish Monarchy

In antiquity, kings and queens were incredibly powerful people, not just symbols. They were often viewed as gods or demi-gods, completely above the law.

The concept of kingship in Judaism differs markedly from other types of monarchy in antiquity. The Jewish king had privileges and powers, but above all, the position came with an awesome responsibility. The king was to represent the ideal Jew, who acted as the role model for the rest of the nation.

To this end, the king was commanded to carry a Torah scroll with him at all times:

And when the king sits on the throne of his kingdom, he will write a copy of the Torah and it will be with him, and he will read from it all the days of his life. So he will learn to fear the Lord his God, and keep all the words of his Torah, and do its statutes. (Deuteronomy 17:18-19)

More than anyone else, the king must recognize there is a Divine power above him, the King of Kings, whose laws even the king must obey. The Jewish king was not above the law; rather he was charged with exemplifying it.

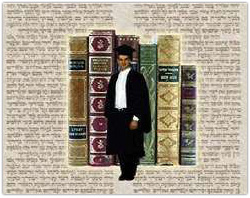

Jewish Education

The Jewish obsession with education is well known. Although it is true that when a child graduates from college, it gives the parents tremendous joy and thereby fulfills one of the "Big Ten" – "Honor your father and mother" – there's a deeper reason for Jewish hyper-achievement in education. The drive to learn is deeply ingrained within us.

The Jewish obsession with education is well known. Although it is true that when a child graduates from college, it gives the parents tremendous joy and thereby fulfills one of the "Big Ten" – "Honor your father and mother" – there's a deeper reason for Jewish hyper-achievement in education. The drive to learn is deeply ingrained within us.

From their very beginnings as a people, Jews have understood the special responsibility in the world, which empowers us to achieve. To gain knowledge and really take responsibility, a Jew has to be literate.

The tremendous Jewish emphasis on education is codified by Maimonides:

Appoint teachers for children in every country, province and city. In any city that does not have a school, excommunicate the people of the city until they get teachers for the children. If they don't, destroy that city – because the world exists only through the breath of children studying." (Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Laws of Torah Study 2:1)

Imagine how different the world would have been if this law was universally in effect a thousand years ago. What a different attitude the Jews had toward education than the rest of the world. No Jewish city ever lacked a school, even in the Diaspora. The French medieval monk, Peter Abelard (1079-1142), wrote about Jewish education:

"A Jew, however poor, even if he had ten sons, would put them all to letters, not for gain as the Christians do, but for understanding of God’s law. And not only his sons, but his daughters." (Peter Abelard, Commentary on Paul's Epistle to the Ephesians, ch. 6)

In 1910, the U.S. Immigration Commission carried out a study on literacy among new immigrants in America. They discovered that the rate of literacy among Jewish arrivals from Eastern Europe was 74%, significantly higher than the 60% overall figure in the U.S. And these were Jews coming from one of the poorest and most oppressed Jewish communities in the world!

Today, Jews comprise about 25% of both the student body and faculty of the Ivy League schools, although in the U.S. they constitute less than 2.5% of the population.

In theory and practice, Jewish communities have always made education a top priority.