Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

5 min read

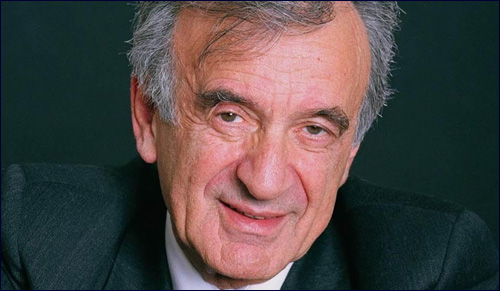

My unexpected encounter with Prof. Elie Wiesel gave me a glimpse into his regal soul.

I didn’t meet Prof. Wiesel, as he liked to be called, until well into my fourth decade of life. Until then, I viewed him as a moral witness to the Holocaust, prolific writer, secular Jew and a poetic soul. His message seemed to speak to the common denominator of our creation in the image of o-d, and how the Holocaust both betrayed and imposed unending wounds on the collective spirituality of mankind.

However upon meeting Prof. Wiesel, I encountered an individual that was quite different of what I had anticipated. In the Fall of 2005, I accompanied leaders and benefactors of the Hasidic communities of Tzfat to Prof. Wiesel’s private office near Park Avenue. We were electrified by his regal bearing. He emerged from behind his desk, surrounded by what seemed like thousands of volumes of writing, research and Jewish seforim, books.

We presented him with a gift of an ArtScroll volume of the Jerusalem Talmud. As he cradled it in his arms, he told us that he studied Talmud each and every day and would not allow a day to pass without immersing his mind in the holy words of the Talmudic Sages.

Our goal was to convince him to accept an honorary award from the Tzfat Fund, associated with the Breslov community, with whom he had shared a special relationship. Although in that meeting he identified himself as a Vishnitzer Hasid, having grown up in the Carpathian village of Sighet, his love and fascination for Rebbe Nachman as a historical figure, storyteller and writer enchanted him. He wrote wistfully about the private moment that he and his family shared when he visited the gravesite of Rebbe Nachman of Breslov, a man with whom he greatly resonated.

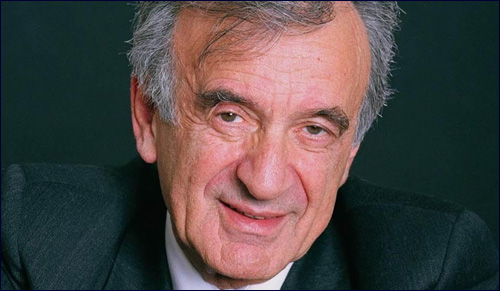

Professor Elie Wiesel and Rabbi Efrayim Koenig

Professor Elie Wiesel and Rabbi Efrayim Koenig

He accepted the invitation to attend the dinner. But it wasn’t just an appearance to accept an award. We designed an evening that would present a dialogue between Prof. Wiesel and Rabbi Efrayim Koenig of Tzfat, on the issues of faith after the Holocaust, Hasidism and the perseverance of the State of Israel in the face of ongoing suffering and persecution.

“What saved my life was Torah study.”

My role was to facilitate a dialogue by translating into Hebrew, Prof. Wiesel’s comments, so that Rabbi Koenig could understand them and respond in his native Hebrew, and then to translate Rabbi Koenig’s remarks from Hebrew to English so that the sophisticated New York audience, could hear and understand. On that night he answered the question of how he identifies himself as a Jew.

One of the themes discussed was Rabbi Koenig’s view of a complete and simple faith in the face of the horror and atrocity of the Holocaust without question, vs. what Prof. Wiesel described as a “wounded faith,” a Jeremiah-like lament or kina, that bemoaned, in God’s presence, the tragedy and destruction that had befallen His chosen People. Regarding the world today he said that evening, “We are all on a train racing to the precipice, the abyss. The only thing we can do is pull the alarm-and we must pull the alarm.”

He also told the audience that he identified himself as a hasidic Jew devoted to Torah study. “What saved my life was Torah study. After the war, the moment I arrived at an orphanage in France, the first thing I asked for was a masechet, a Talmudic tractate I had brought with me when I entered the camps. I would not be who I am today without the influence of Rava and Abaye, Rabbi Akiva, Rebbe Yishmael and actually, the Baal Shemtov. I have never given up learning... I learn Torah every day because that is who I am. So I am a Hasid in the best sense of the word, despite the fact that I don’t look like it. Perhaps if there had been no war, I would be wearing a shtreimel today - and I say this with nostalgia.”

Especially in his later years, Prof. Wiesel chose to reaffirm his childhood identity as a young Vizhnitzer hasid. I am told that he relished the opportunity to lead the prayer services at the modern Orthodox Fifth Avenue Synagogue using the hasidic nusach and nigun that he remembered from his youth. He transported the amud in Manhattan to a shtibel somewhere in the village of Sighet, Romania. The sounds were identical, and so were his feelings.

I came to understand that Prof. Wiesel’s regal way, the honor that he received from world leaders across the globe, was intrinsically bound to the shining presence of his unique Hasidic soul, His essence to them reflected a small spark of the glory from our most royal Jewish ancestors. In the eyes of world leaders he was graced with cheyn (charm) akin to Joseph in the eyes of Pharaoh. In his moral writings they saw reflection of the universally lauded wisdom of Solomon, and in his emotional and poetic eloquence they heard an echo of the Psalms of King David.

Prof. Wiesel’s legacy is more than the Holocaust. It is a demonstration of how a Jewish soul, tormented by the pains and the suffering of his People, can shine a reflection of God’s holy, hidden light – the light that lifts our human depravity from darkness and inspires us to live moral, honorable, decent lives; to protect and defend the helpless and respect the traditions and wisdom that God implanted into His holy Torah and to the souls of His People, Israel.

The Jewish People’s role is to be light unto the nations, we all aspire to it. Prof. Wiesel, the Vizhnitzer Hasid from Sighet, embodied it. May his memory be a blessing.