An Open Letter to University Presidents

An Open Letter to University Presidents

8 min read

Invisible, inaudible, inanimate: my adventures in a wheelchair.

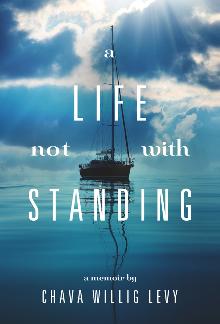

The following is excerpted from Chava Willig Levy's new memoir, A Life Not with Standing. Chronicling the adventures of an iron lung alumna, it shatters stereotypes about people with disabilities, enabling others to view disability with pride, not prejudice.

I was raised in a joy-filled home. One of its most joy-filled days was April 12, 1955, when Dr. Jonas Salk announced that his polio vaccine worked. Four months later, at the age of three, I contracted polio.

Years of hospitalizations and surgeries had me hungering for home. But with each hospital discharge, one destination had me chomping at the bit to fly the coop. My ninth birthday long behind me, I had yet to attend school. Except for my synagogue’s afternoon program, home and hospital instruction was all I knew. The only advantage to this lonely segregation was its tight quarters. They afforded me the chance to minimize wheelchair use; at home, for example, a few steps from bed to kitchen table, my ersatz school desk, were well within my ambulatory range.

Finally, a chance to go to school like everyone else, with everyone else. I was wrong.

Finally, one spring day, after years on the New York City Board of Education’s waiting list, I was admitted to a special education class. Finally, I exulted, a chance to go to school like everyone else, with everyone else.

I was wrong. Each weekday morning, my special ed classmates and I got off the segregated school bus, entered our segregated classroom and – except for occasional visits to the physical therapist’s office or the separate “handicapped” bathroom – stayed there until the segregated school bus brought us home. We never mingled with able-bodied kids, not in the classroom, not in the library, not in the cafeteria (even though it was just down the hall, we were never allowed to eat there – an insurance risk, we were told).

The only advantage to this obscene segregation was, once again, its tight quarters. They afforded me the chance to minimize wheelchair use, so much so that my wheelchair stayed at home. A few steps from my front door to the school bus, a few steps from the school bus to the health conservation classroom (equating disability with illness was axiomatic in the 1960s; 50 years later, it still is) and reversing the order when homeward bound – nothing to it.

But then an outing to the Bronx Zoo took place in June. Imma came along; my wheelchair didn’t. For the first 15 yards, I loped jauntily among my classmates, most of them in wheelchairs. Then, without my saying a word, without my even knowing that I needed it, Imma placed her right hand under my left elbow. Ten yards later, her support was insufficient. I began to lag behind, out of energy, out of breath. Five yards later, Imma guided her enervated daughter to a bench, where we remained until my classmates paraded back.

I’m not sure if I realized it before. I certainly realized it then: My wheelchair was my friend. It still is. To this day, the final stanza of Nurse Callahan’s ditty often comes to mind:

One finger, one thumb, one arm, one leg, one nod of the head, stand up, sit down

Keep moving.

Stand up. Sit down. Either way, the point is to keep moving. For me, sitting down in a motorized wheelchair (I took the leap from manual to motorized wheelchair in 1980) offers a faster, more liberating, less exhausting way to keep moving. For so many others, the mere thought of it fills them with revulsion.

In the 1990s, when I lived on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, my chariot of choice was a three-wheeled motorized scooter. Zipping along West End Avenue, I’d often greet elderly people plodding painstakingly with walkers, their pallid faces exuding exhaustion.

“I wonder if you’d find it easier to get around in a scooter like mine.”

“Oh, no!” I’d hear, and sometimes, “I’d rather die!”

I’d wish them a good day and sprint ahead, reaching the corner in seconds, leaving them far behind.

After that exhausting Bronx Zoo school outing, I didn’t mind becoming a more frequent wheelchair user. What I did mind was becoming a wheelchair.

The year was 1962. Another school year, another school trip. I was sitting in a yellow “handicapped” school bus, the kind equipped with a hydraulic lift and absolutely no shock absorbers. My class was on its way to the Museum of Natural History. After battling traffic for over an hour, the bus driver pulled into the parking lot and drove toward the museum’s rear – and (surprise) only accessible – entrance. Before he had a chance to turn off the ignition, a museum guard rapped authoritatively on the bus’s windshield and pointed to a far-off sea of yellow, where school buses apparently were required to park. Full of self-importance, our driver lowered his window and bellowed in the most mellifluous Brooklynese, “I gotta pock heeya. I got wheelchairs!”

Now that was a difficult shock to absorb. I knew something was dreadfully wrong with being defined as an inanimate object. I wanted to call out, “You mean, ‘I got people in wheelchairs!’” But I was only ten years old. I didn’t know how to speak my mind.

I have many more tales out of school to tell, but I can’t resist telling a tale not of my own: a tale from the classic television series The Twilight Zone, entitled “Eye of the Beholder.” For twenty of the twenty-five minutes Rod Serling needed to weave his riveting story, the bandaged face of a hospital patient is the only one in view. When we meet her, she is about to endure the plastic surgeon’s ninth and final attempt to correct, or at least diminish, her severe disfigurement. As the last bandage is about to be removed, the camera swings around. The doctor exclaims, “No change. No change at all!” The camera cuts back to the patient. For the first time, we see her face. It is ravishingly beautiful. Instantly, the camera cuts to the doctors and nurses. For the first time, we see their faces. They are repugnant, pig-like.

For me, the most powerful moment in this drama occurs well before that climax. The doctor tells his patient, “There are many others who share your misfortune, people who look much as you do. Now, one of the alternatives, just in the event that this last treatment is not successful, is simply to allow you to move into a special area in which people of your kind have been congregated.”

And the patient, her face swathed in bandages, cries out, “People of my kind? Congregated? No, you mean segregated!”

“Eye of the Beholder” first aired in 1960. Perhaps the eight-year-old I was then would not have appreciated its profundity. Still, I wish I had seen Serling’s masterpiece before the shame and rage that segregation engendered had taken their toll.

Because I was a child, it hurt having no voice to demand a voice.

Educational segregation not only made us invisible, it made us inaudible. Although we could attend our school’s talent shows, we were never allowed to participate in them. I knew I had a good voice. It hurt being barred from sharing it. And because I was a child, it hurt having no voice to demand a voice.

Not surprisingly, the adult I am today bristles when people assume I can’t speak for myself (a waiter, for example, might turn to my friend and ask, “What does she want to eat?”). Still, were it not so infuriating, inaudibility can occasionally be funny. Wishing to sing her praises, I once asked a physical therapist for her supervisor’s name. She was delighted to provide it: Amy.

“Good morning. Rehabilitation Services, Orthopedics Department.”

“Hello. May I speak to Amy?”

“Who are you calling for?”

“Amy.”

“No, who are you calling for?”

“Um, Amy.”

“No, who are you calling for?”

“Amy.”

By this time, the woman on the line was exasperated. So was I. “Wait a minute,” she snapped. Then she asked incredulously, “Are you the patient?” Only then did I realize that “Who are you calling for?” meant “On whose behalf are you calling?” The notion that “the patient” could be calling on her own behalf never dawned on her.

The invisibility, inaudibility and anonymity of my special education days may be long gone. But every now and then, I still get to be inanimate. Fifty years after my school bus driver hollered, “I gotta pock heeya. I got wheelchairs,” a friend and I attended a dazzling concert at Carnegie Hall. At its conclusion, we proceeded from the lobby to the sidewalk. A man several inches in front of us said to his companion, “Let the wheelchair pass.”

The invisibility, inaudibility and anonymity of my special education days may be long gone. But every now and then, I still get to be inanimate. Fifty years after my school bus driver hollered, “I gotta pock heeya. I got wheelchairs,” a friend and I attended a dazzling concert at Carnegie Hall. At its conclusion, we proceeded from the lobby to the sidewalk. A man several inches in front of us said to his companion, “Let the wheelchair pass.”

I smiled and said, “You mean, ‘Let the woman in the wheelchair pass.’”

The man retorted, “Well, you’re a part of it.”

“No,” I replied, “it’s a part of me.”

A Life Not with Standing is available as a print book and as an e-book.