An Open Letter to University Presidents

An Open Letter to University Presidents

14 min read

A pilgrimage to discover my family's roots that the Nazis tried to destroy.

I was 12 when I first noticed the photo. An elderly couple, she wore a kerchief, he a long beard. They sat in the front seat of an open wagon pulled by a large horse. Thatched cottages of an ancient looking shtetl (town) loomed in the background.

"Wow, Grandpa!" I asked earnestly. "How did you get this great photo from Fiddler on the Roof?"

To my astonishment he replied, "Those are my parents. In my hometown of Staszow (pronounced Stashov) in Poland."

To my astonishment he replied, "Those are my parents. In my hometown of Staszow (pronounced Stashov) in Poland."

I learned then that my mother's grandparents, together with her aunts and uncle and their 22 children who I had barely heard of before, were murdered in the Holocaust. Yet growing up in the comforts of Canada, details about the war, my relatives and Staszow remained as distant as the scene in the photo.

That all changed last month, when I was invited to participate in an Aish HaTorah Faculty visit to Poland. Meant to help us integrate more fully the reality of that tragedy -- and the potential tragedies if we fail to take the necessary action against our enemies of today -- 60 of us were to set out to visit the death camps and the ghettoes. I decided that if I would already be in Poland, perhaps I should include a visit to the old shtetl. But what remained of Jewish life there? Was there a way to learn where my family lived? Where to even start?

Google.

Searching for "Jewish Staszow" (after 10 attempts at other spellings), I discovered an article by a man named Jack Goldfarb, who had made a similar pilgrimage to Staszow and helped restore the old Jewish cemetery. Searching further, I clicked on a blog by a Danny Miller. Suddenly there appeared on my screen a picture of my great-great-uncle, Itcha Meyer Korolnek! Danny is his great-grandson, now a screenwriter in LA. He reminisced in his blog about the stories he'd heard from Itcha Meyer about life in Staszow. This led me to info from a 1932 Staszow Town Registry, which contained my great-grandparents' home address!

Another Google hunt led me to the marriage records of my great-grandparents. (Many of these records are thanks to the Mormon Church's efforts to document and posthumously baptize the Jews of Europe!) Leibish Unger and Esther Goldkind married in 1888. Esther gave birth to eight children, including my grandfather and his twin in 1903. Four children emigrated to Toronto in the 1920s, and the rest remained behind, in part because of their fear of a "less Jewish" environment abroad.

I learned about the remaining "Jewish sites" to be seen, tracked down a local English-speaking guide, and transportation. Everything was complete!

A few weeks ago, on a Thursday morning, my twin brother, Raphael, and I were picked up by a young Polish driver. I was feeling the drama and the excitement: the first return of our family since November 8, 1942, when the Jews of Staszow were driven from their homes and delivered to death at the Belzec concentration camp.

A few weeks ago, on a Thursday morning, my twin brother, Raphael, and I were picked up by a young Polish driver. I was feeling the drama and the excitement: the first return of our family since November 8, 1942, when the Jews of Staszow were driven from their homes and delivered to death at the Belzec concentration camp.

History of the Town

Jews had lived in Staszow since the 1400s. In 1610, the Christian ruler of the area, looking for a pretext to exile the Jews from his province, orchestrated a blood libel. They accused a local Jew of killing a Christian child to use his blood for Pesach matzah, the unlucky man was executed and the remaining Jews deported. Their possessions were confiscated and used to build the dominating church tower, which stands till today over Staszow. Invited to return by a subsequent ruler, Jews began to flourish there.

Like many other shtetls, by the time of World War II, Staszow was 60 percent Jewish, and on the whole enjoyed a rich Jewish life amongst their non-Jewish neighbors. (Except for the occasional small pogrom of course, like one in 1932.) They had a huge central synagogue, a Jewish inn, kosher butchers, mikvahs, a Jewish hospital and two yeshivot.

When the Germans conquered Poland in 1939, all that changed. Their quiet life was shattered. For two years my family lived a period of relative calm, but anxious worry. "Thank God we're well and we're coming along as best we can," my great-aunt wrote in May 1941. "If things will be quiet then it will be good. In the home everything is in the best order, you shouldn't worry about anything."

We are so worried. We are so nervous.

Perhaps more honestly, my grandfather received this note on the back of a photo from another aunt: "We are so worried, and we don't know what will be in the future. We are so nervous. Please answer soon."

That was the last the family was heard from.

With the help of archives I found at the New York Public Library website, I succeeded in piecing together the last months of my 32 relatives. On December 30, 1941,the uneasy quiet was broken. Staszow woke up to posters in the streets announcing that no Jew could leave the town. Transgressors would be shot. From that fateful day, their end was sealed and the disastrous campaign against them mounted quickly. On January 6, the "Fur Action" was announced: Jews were obliged to hand over all fur garments. Failure to comply punishable by death. Several Jews, not yet fully aware of the Nazi methods, were found in possession of furs and were shot.

On January 15, no Jewish business could operate except under the supervision of a German or Pole. The next few months saw regular incidents of mass robbery, beatings and occasional lynchings. By Passover, the last for the Jews of Staszow, they began hearing of the extermination actions in other shtetls around Poland. A 19-year-old girl tried to escape to the forests but was caught and shot. The holiday passed in great trepidation.

On June 15, the Ghetto Decree was announced. The 5,000 Jews of Staszow were forced to move into two small sections of the town, and their last meager means of making a living were cut off. A 6 p.m. curfew kept my family and the others crowded in strange homes in the worst sanitary conditions, 10-15 packed in a room. Another 2,000 people from neighboring villages were added to this pile of misery.

Mayor Suchan took every advantage to extort, terrorize and torment the Jews without relent. In August, a Jew was shot for baking bread, another for slaughtering a cow and four women for preparing a piece of leather.

The Jews desperately sold any last remaining belongings not already pilfered, for pennies. Homes, though, could not be sold. The Poles knew it was only a matter of time until they would be theirs: "A free new home for every family."

Polish peasants brought large sacks to gather the Jewish spoils.

By November 7, the Jews were well aware of their impending doom. A survivor wrote, "Maybe it is the last Shabbat, God forbid, of the fine and extensive Jewish community of Staszow. One does not wish to believe that the angel of death is already preparing to take our innocent souls. Everybody runs to see his near and dear ones, to console the dejected, to plan means of escape, and also to say goodbye to one another. We want to be together during our last moments."

That night, the community was ordered to prepare a feast for 150 members of the roving Nazi "resettlement" unit which was making its way from town to town. In anticipation, peasants from the vicinity had already gathered with large sacks to gather the spoils, impatiently asking "Hasn't it started yet?"

On the mournful dawn of November 8, 1942, the Jews were ordered to appear in the Market Square by 8 a.m. From there, 5,000 abandoned souls were marched off forever. Before they even left town, 189 had been murdered in the streets.

Running for the Bus

All this information generated intense feelings about my return to the shtetl of my ancestors. On one hand, it was the place drenched with the blood of my family. On the other, it was where they had lived, worked, laughed, celebrated births, marriages, bar mitzvahs, Shabbat and holidays, for so many generations.

When I told our driver the purpose of our visit, he hesitantly asked: "Had we heard whether Poles participated in the Holocaust in any way?" We were dumbstruck, not finding words to answer. Finally, we shared with him the common knowledge that Poles were considered by survivors to have been complicit with the Germans.

He said that growing up in Poland, where every student must visit Auschwitz and studying the Holocaust is mandatory, the Polish role in the fate of the Jews has been erased! As a hotel employee, he had once heard a lecture in sensitivity training (Jews are the number one tourist group to the country) where he was told that Poles were active participants, but was wondering if it was really true.

"In Staszow," I responded, "1,000 Jews found shelter in hidden bunkers and barns to avoid the final deportation. Of those, 900 were turned in by their neighbors."

Not 15 minutes passed, when he received a first hand illustration. As we drove toward Staszow, we decided to stop at the burnt-out synagogue in the town of Krasnik. The taxi pulled over to ask directions from an old lady standing by the road. When she heard the word "synagogue," she glanced quickly at us in the back seat, grabbed her bags, and raced away from us at granny-lightning speed.

Stunned, I turned to our driver and said, "Looks like she doesn't like Jews much."

Equally shocked, he replied, "No, I think she was just running for a bus." (There was no bus.)

A middle-aged woman yelled at us, "Go away!"

After finding and visiting the synagogue, we exited to the sight of a middle-aged woman in the back of a car, yelling something to our driver over and over. We asked what she was saying. Reluctantly, our driver confessed, "She's saying 'Go away!'" We had just encountered more hatred in the first hour off our tour bus, than in our entire lives in Canada! (Later, he cautioned us, that the word "Zyd," meaning Jew, "is not a nice word to use.")

With trepidation, we finally closed in on Staszow, now a picturesque village of 18,000. Zero Jews. We met our guide, Simon, in the Market Square, a large quaint open area surrounded by shops. As I stepped out of the car, my kippah proudly flashing on the top of my head (I decided not to wear a baseball hat -- I wanted to let the villagers know that we're still here), people all around stopped in their tracks and stared. For minutes.

From this spot 64 years ago, my great grandparents and their offspring had been led to their deaths in an act of hysterical evil that today's pastoral scene belied.

Raised in Staszow, Simon quickly pointed out that most of these stores were once owned by Jews. We decided to begin with the site of the synagogue. Once home to 5,000 congregants, it had been torn down ("because it was not being used") and replaced by an efficient-looking green office building. A small plaque noted the significance of the site.

Strolling back to Simon's car, under the watchful eyes of what felt like everyone in Staszow ("We don't get a lot of visitors here", Simon suggested helpfully), he pointed to a section of the sidewalk. "Once, after a snowfall, the whole sidewalk was covered with snow except for one spot. Someone noticed, and deduced there must be a Jewish family hiding in a secret basement below. The Nazis were called in and the family taken away."

As we circled the square in Simon's car, he shared with us what he had heard from his aunt, who lived through the war. "The day the Germans entered the town, the first thing they did was grab a rabbi. They tied him by his hands to one of their cars, and dragged him round and round this square until he died."

Next stop was the local history museum, located nondescriptly in the basement of a Communist-era block apartment building. We expected it to be devoted to the memory of the 60 percent of the community which had been obliterated. We were someone surprised to discover the first room full of Staszow's famous sabers, and photos of prize Arabian horses. The next large room wasn't more relevant either, but moving through it, we were guided to a closet-sized alcove: the memorial to 5,000 Jews. A few photos, a map of the ghetto, and a couple of cheap menorahs filled most of the "Jewish wing."

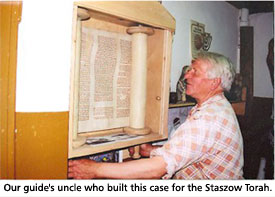

The prize possession, though, was a Torah scroll from the old synagogue. As we studied it, we were abruptly joined by an older ruddy-faced gentleman with a large smile who began to speak to us rapidly in Polish. He was Simon's uncle -- apparently tipped off to the presence of Jewish visitors -- who had personally handcrafted the glass and wood case that housed the Torah. He assured us that they were aware of the scroll's holiness, and had washed their hands before handling it. He recounted how the Torah had been rescued from the burning synagogue by a 9-year-old boy.

The prize possession, though, was a Torah scroll from the old synagogue. As we studied it, we were abruptly joined by an older ruddy-faced gentleman with a large smile who began to speak to us rapidly in Polish. He was Simon's uncle -- apparently tipped off to the presence of Jewish visitors -- who had personally handcrafted the glass and wood case that housed the Torah. He assured us that they were aware of the scroll's holiness, and had washed their hands before handling it. He recounted how the Torah had been rescued from the burning synagogue by a 9-year-old boy.

I, Survivor

We headed off to our next destination: the family home. What would we find? The same old home? (Many still existed throughout the town.) Something familiar from the photo which started this odyssey? At the corner of the street, an ancient-looking grey wood structure stood, with a couple of derelicts at the door. This was the old Jewish bathhouse -- mikveh, no doubt -- which was now occupied by "low income residents."

At last we found the address. We were disappointed to see that it was a newish home, but nevertheless we were overcome with feelings of nostalgia. In the back, an aged barn and garden gave us a taste of what it might have been like. Across the road we excitedly spotted a place that looked right out of the pictures of the shtetl, complete with old wooden wagon and live chickens! I pulled out my camera, when suddenly an old woman began to scream and headed toward us from the coop. (We had been warned that Poles often react this way to foreigners, suspecting that they're Jews coming to reclaim lost property.) Simon calmed her down, but by that time several other neighbors had emerged from their homes to witness the excitement. We entered into a pleasant conversation with the next door neighbors, who weren't quite old enough to be worried about their property.

After the requisite photo shoot, we continued through the picturesque, impossibly quiet streets, until we came upon a massive tower and impressive Medieval church. This, then, was the "Blood Libel" tower built from plunder of the first exile of Staszow's Jews in 1610.

Every tombstone had been smashed.

Before taking leave of Staszow we had one final stop, the cemetery where Jews had been buried for six centuries. Every tombstone had been smashed. One more recent tombstone brought the tears to our eyes. It read, "Here lie the remains of two people, one a teenager, one in his 40s, whose remains were found in the year 2000 in a basement bunker. Assumed to be Jews who had hidden during the war, they were re-interred here."

On the road out of Staszow, a road filled with blood and tears that will eternally cry out from the earth, Simon filled in the final details of our family's last day on earth. "All the non-Jews were instructed to bring every wagon and horse to the Market Square. At 10 a.m. the miserable procession began to move out of town. They were marched on this road for five miles until they reached the town of Niszen. Here, a mass grave was dug and 740 victims were slaughtered. The rest continued another 10 miles until they reached the train station. They were packed in, 100 to a cattle car, and shipped off to Belzec for extermination."

Life expectancy: four hours.

The Jewish community of Staszow was no more. I don't look at that picture of my great grandparents and their wagon the same way anymore. They are now a conscious part of me. I am their memory. I am their survivor.