Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

11 min read

How I discovered the keys to social activism in Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Jerusalem.

I went into the world because I wanted to find what is true. I wanted to genuinely make the most of this infinite and wholly beautiful opportunity called life, to discover what the world is, to ring hard the bells of my beliefs and see if they did not break. I wanted to experience with no fear, and inhale deep all the truth I could — to shed attachment through austerity and courage, to banish illusion. And not, when life came to close, to discover that I had not lived.*

These are the words I wrote to myself as I embarked on a year-long fellowship to study my passion of “social-environmental justice,” a broad field of study and action combining social education, economic programs, and technological solutions designed to foster social structures in which people have fundamental human rights and access to key environmental resources.

Thomas J. Watson who, as head of IBM World War II, provided the punch-card technology used by Nazi Germany to keep the killing machine running smoothly, was later overcome by guilt and worked to ensure that such atrocities never occurred again. To this end, he established a fellowship for college graduates, providing a year-long grant for “independent, purposeful exploration and travel – in an international setting – to enhance capacity for resourcefulness, imagination, openness and leadership, and to foster humane and effective participation in the world.”

By the end of that year, I was to make a surprising, life-altering discovery.

It was with this idealistic mission that I embarked upon my “Watson year.” By the end of that year, I was to make a surprising, life-altering discovery. I realized that the truth I sought wasn’t to be found “somewhere out there,” but was rather rooted in my own Jewish heritage. Though I grew up with a mixture of appreciation and ambivalence for Judaism, T.S. Eliot’s words later rang true: “And the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started, and know that place for the first time.”

Year of Exploration

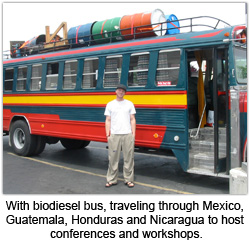

I departed from Washington D.C. to Honduras, commencing my year of studying “social/environmental justice” (SEJ) through visiting and working with governmental programs, social enterprises, nonprofits, and educational institutions around the globe. I traveled to the coastal plains of Guatemala to investigate sustainable agriculture, to the gang-ridden and marginalized favelas (shanty towns) of Brazil studying participatory democracy, and to the dwindling rain forests to understand how communities unite against the destruction of their environment.

I departed from Washington D.C. to Honduras, commencing my year of studying “social/environmental justice” (SEJ) through visiting and working with governmental programs, social enterprises, nonprofits, and educational institutions around the globe. I traveled to the coastal plains of Guatemala to investigate sustainable agriculture, to the gang-ridden and marginalized favelas (shanty towns) of Brazil studying participatory democracy, and to the dwindling rain forests to understand how communities unite against the destruction of their environment.

In India, I witnessed startling contradictions: some of the world’s greatest displays of luxury and economic development, alongside some of the world’s most crushing poverty. I encountered millions living in rural communities with only a singular pond for bathing, bathroom needs, animal cleaning and yes — drinking water. In such places, 80 percent of death and morbidity are due to water borne disease (Gram Vikas, 2008) and globally about 1.5 million children die each year from the lack of hygiene and unclean water (WHO, 2007).

Missing Human Element

By the end of the year, however, it became clear to me that the world of social-environmental justice had largely overlooked the most challenging and important factor in affecting change — individuals. Nietzsche once said that “to be human is to be elsewhere,” suggesting that we tend to run away from life’s hardest challenges while pretending to be confronting them. The problem with SEJ’s emphasis on mechanisms for change — economic policies, nongovernmental programs, technological solutions — is that they are focused on creating change through policy, not people. These solutions are cold “systems” that can be examined and studied – but that lack the deep human investment that a healthy world demands.

I discovered that where real change was taking place, the key driver was people taking responsibility to transform their reality at a personal, intimate level. It wasn’t so much about farmers having the appropriate methods to preserve their lands, or about affordable water filters, or digging wells. It was about a social and cultural momentum that inspires ownership and leadership.

I discovered that where real change was taking place, the key driver was people taking responsibility to transform their reality at a personal, intimate level. It wasn’t so much about farmers having the appropriate methods to preserve their lands, or about affordable water filters, or digging wells. It was about a social and cultural momentum that inspires ownership and leadership.

All these programs overlooked the importance of trust, care, mutual understanding and ultimately love.

I observed the failure of initiatives rooted in the belief that technology or policies alone could solve big problems. In Honduras, I saw that while farmers had adequate resources and funding at their fingertips for land stewardship, their lack of personal ownership translated into a beleaguered project at a cost of several million dollars. A hygiene program in the south of India failed when hundreds of bathroom units were used as cow stalls — while the villagers reverted to their traditional unsanitary practices. In the Kolwan Valley, India, wells were broken and abandoned just a few years after installation because the community did not possess the know-how to maintain them. Once the nonprofit team left, so did the human investment needed to keep the wells running.

All these programs overlooked the importance of trust, care, mutual understanding and ultimately love. As such, communication between the project implementers and community recipients broke down, and the projects ultimately failed.

People Change People

With thousands of projects globally and millions of dollars invested in this approach, it was difficult for me to break out of this mold and recast my understanding of how to best generate positive change in the world. It took nearly the entire year to build a new understanding, which crystallized for me during the final three months of my program. I conducted a series of interviews at one of India’s top business schools, Institute of Rural Management Anand, interviewing over 60 students who had chosen to focus on social enterprise rather than purely capitalistic endeavors.

Midway through one interview with a particularly inspiring student, I asked her, “What do you think planted in you this drive to change the world? There are many other people with a similar background and education who did not choose such an altruistic path.”

She responded, “In school, on the news and everyday in the streets, I saw the problem of poverty in our country. This inspired me to strive to make a difference.”

She responded, “In school, on the news and everyday in the streets, I saw the problem of poverty in our country. This inspired me to strive to make a difference.”

I pressed further: “Yet almost all of your classmates, who also know of these problems and are exposed to them on a daily basis, have not taken responsibility to affect change the way you have. What makes you different?”

She was startled and, as if stumbling upon a forgotten dream, replied, “My grandfather taught me to care about the world.” This man had fought for independence and knew what it meant to risk one’s life for an ideology. He shared these stories with his granddaughter and acted as her spiritual and moral guide. The result was a passionate and highly capable young woman, yearning to make a difference in the world.

From this conversation and others like it, I drew the following axiom: People must be invested with love and care if they are to invest love and care into their community and the world. Social heroes such as Martin Luther King Jr., Ghandi and Mandela did not arise out of a vacuum. Somewhere in their lives, they had a close mentor who loved them, nurtured their humanity, and taught them to truly care.

It was then that I concluded: Good parents, siblings and children, along with good friends, mentors, community members and neighbors, make the world flow positively. The foundation for social-environmental justice — indeed, the very marrow of its being — is founded in personal relationships.

The Jewish Model

Perched in the Himalayas of Dhramsala, India, I began the process of reflection and exploration, searching for a model that accounted for the import of personal relationships in its theory of change. I had studied a wide array of models for solving the social and environmental challenges of our generation, yet none seemed to fully grasp how the most enduring and resounding change emanates through building the right relationships. Through reading books, journal articles and essays, I stumbled upon the Jewish philosophy of Tikkun Olam, repairing the world.

Perched in the Himalayas, I stumbled upon the Jewish philosophy of Tikkun Olam, repairing the world.

In contrast to the classic model of practical action, Tikkun Olam recognizes the holistic basis of creating positive change. Tikkun Olam understands that each component of reality is interconnected. Just as you cannot repair an automobile without understanding how all the components fit together, so too healing the world cannot be viewed as separate from spiritual and communal repair. They are all vital aspects of an infinitely-faceted Reality.

The pinnacle of this ethic is the Torah commandment to “Love your neighbor as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18). We are responsible to treat each other with the greatest care and love, attending to the holistic needs of others as we would our own selves. We must be good family members, neighbors and citizens, and only from there — taking responsibility at a personal and holistic level — can the beauty of Tikkun Olam unfold.

Implicit within the command to “love your neighbor as yourself” is the idea that we must also love ourselves wholeheartedly. As Rabbi Hillel asks, “If I am not for myself, who will be for me?” This is the heart of Tikkun Ha’nefesh — “reparation of the soul” — which is Judaism’s complementary philosophy to Tikkun Olam. Those involved in practical change often develop myopia for direct action, and forget to appreciate that our souls and personal selves are part-and-parcel of the change we build. Some of the most effective peace activists I met during my Watson year were also some of the most angry and depressed. Their families, friendships and personal lives were a wreck, and though there was a strong ideology pushing them to generate positive external change, internally there was a self-denying struggle of desperation and forlornness.

Implicit within the command to “love your neighbor as yourself” is the idea that we must also love ourselves wholeheartedly. As Rabbi Hillel asks, “If I am not for myself, who will be for me?” This is the heart of Tikkun Ha’nefesh — “reparation of the soul” — which is Judaism’s complementary philosophy to Tikkun Olam. Those involved in practical change often develop myopia for direct action, and forget to appreciate that our souls and personal selves are part-and-parcel of the change we build. Some of the most effective peace activists I met during my Watson year were also some of the most angry and depressed. Their families, friendships and personal lives were a wreck, and though there was a strong ideology pushing them to generate positive external change, internally there was a self-denying struggle of desperation and forlornness.

As Martin Luther King Jr. once said, “People must come to witness the flesh and blood embodiment of an ideal before they can be moved to fully believe in it.” Without appropriate Tikkun Ha’nefesh we cannot arrive at a full Tikkun Olam. Just as Tikkun Olam takes a holistic view of what change truly means, so too does the command to “love your neighbor” demand that we first care for ourselves, and only then can we reach the greatest heights.

Next Steps

This fundamental shift in perspective deeply informed how I relate to the world as an agent of change. I used to believe that although I was Jewish, that heritage did not implicate me in any unique manner. I assumed that as a member of liberal-progressive society, I was to transcend such anachronistic divisions of peoples based on ethnicity and religion. However, I have found the contrary to be true: By embracing my heritage and steeping myself in Jewish consciousness, I am gaining access to the deepest parts of myself, unlocking and sparking my highest potential.

After the Watson year, I took these revelations with me to Guatemala where I joined old friends and colleagues to co-found a nonprofit called Semilla Nueva (Spanish for “New Seed”) which helps farmers gain food and livelihood security through the power of land stewardship. With these lessons in mind, we rooted our nonprofit in the philosophy of building genuine relationships with farmers and community leaders, and collaborating with them as friends and comrades.

After the Watson year, I took these revelations with me to Guatemala where I joined old friends and colleagues to co-found a nonprofit called Semilla Nueva (Spanish for “New Seed”) which helps farmers gain food and livelihood security through the power of land stewardship. With these lessons in mind, we rooted our nonprofit in the philosophy of building genuine relationships with farmers and community leaders, and collaborating with them as friends and comrades.

I had too many questions than could be answered in Guatemala. I came to Jerusalem.

Though it was tremendously meaningful to apply this aspect of Jewish consciousness so tangibly to life, I found myself wanting more. Over the course of the next two years, through my amazing “Partner in Torah,” Daniel, and independent learning, I continued to explore Jewish thinking. Eventually, I realized that my metaphysical relationship to Reality is the definitional tenet of life, and I had too many questions than could be answered in Guatemala. I began researching study opportunities in Israel and decided on a two-month program at Aish HaTorah.

The experience impacted me beyond my wildest expectations, and through that tiny crack in the door that Aish helped open, I caught a glimpse of the infinite wisdom and value contained in our Jewish heritage. However, at the end of two months, my time was up and there were a great deal of responsibilities awaiting me. With a heavy heart, I packed my bags and returned to Guatemala.

It quickly became clear that my choice was not sustainable, and that there was a calling for me to continue studies in Israel. It was perhaps the hardest choice of my life to leave Guatemala after having started so much with my close friends, but the opportunity seemed paramount to delve fully into Jewish studies. And it was “now-or-never.” After taking the next several months to help my colleagues better establish our nonprofit, I came back to Aish Jerusalem, where I am now studying full time. It feels like being on a superhighway of growth and learning, and every day I appreciate the opportunity to engage in Tikkun Ha’nefesh (repairing my soul), empowering my goal of Tikkun Olam.

How do I plan to translate my studies into action? I plan to address that question in a future article.

* Inspired by Thoreau's "Walden" pg 359