Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

10 min read

How he and his tefillin survived.

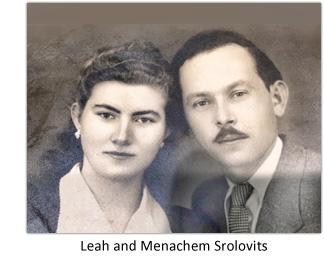

My father, Menachem Srolovits, was born in 1915 in a town outside Budapest. He was the oldest of 11 children in a chassidic family. As a child, Menachem was very thin – but he was strong. When I look at pictures of him, I think he looked like Clark Gable from “Gone With The Wind” – a handsome man with slicked-back hair, a trim mustache, smooth skin, and piercing eyes.

On the occasion of his bar mitzvah, Menachem received a pair of tefillin from his parents.

Menachem’s parents were once wealthy; they owned real estate and hired Gypsies to help around the house. But when he was a teenager, the family fell on hard times. He understood that finances were tight at home, so he found a job in a matzah bakery. Although he worked 10-to-12-hour days, he made time to put on tefillin and thank God for all his blessings.

Menachem was inducted into military service in 1941 as an assistant assigned to a high-ranking officer in charge of a large division. The Hungarian government mandated all young men to serve in some capacity. During the earlier years there had been no overt signs of hatred toward Jews, but that changed rapidly. As life grew worse for the Jews throughout Europe in 1943, and as Hitler gained more power and started rounding up Jews in Poland and elsewhere, the treatment of non-commissioned Jewish soldiers started to deteriorate. The commander, who liked Menachem, allowed him to keep his tefillin inside their little zippered blue bag, which he kept in his deep-pocketed coat.

As World War II spread throughout Europe and the Hungarian Jews were rounded up by force and taken to camps, Menachem became a prisoner of war, held by the Hungarian and German armies somewhere on the Russian border. He had a very powerful voice, so the commander demanded that he sing Hungarian songs to several hundred soldiers whenever they were at the main army base, far from the front line. In return for singing, Menachem received extra food and was permitted to keep his tefillin.

As World War II spread throughout Europe and the Hungarian Jews were rounded up by force and taken to camps, Menachem became a prisoner of war, held by the Hungarian and German armies somewhere on the Russian border. He had a very powerful voice, so the commander demanded that he sing Hungarian songs to several hundred soldiers whenever they were at the main army base, far from the front line. In return for singing, Menachem received extra food and was permitted to keep his tefillin.

As the war in Europe got worse, Menachem, along with a small group of Jewish prisoners, had to dig ditches by the front line while bullets whizzed by them. It was so cold in Russia that many of his fellow prisoners froze to death. It was common for the prisoners to swap clothing and shoes with the dead prisoners for better ones. Since the ground was frozen solid, none of the Jewish prisoners were buried properly.

Menachem was very concerned he might not make it through the war. He was becoming thinner and thinner as the weeks and months passed. Jewish prisoners all around were dying from frostbite or bullets from the Russian soldiers. They constantly were being pushed to different locations, with very little rest.

One night, the entire group of soldiers and Jewish prisoners stopped in a remote Russian farm. The soldiers slept in the warm house, while the Jews were sent to the unheated barn with the pigs and horses. That was the night when Menachem held onto his tefillin tightly and asked God to please watch over him as he tried to escape. Menachem had enough. He was going to take a chance and risk his life. If he succeeded, he would finally be free.

Gunshots rang out and Menachem collapsed in the snow.

When one of the guards was distracted and looked away, Menachem ran across a snow-covered field. The soldier screamed “Stop! Stop!” but he kept on running. Several gunshots rang out, and one bullet hit Menachem’s right leg. Menachem ran a few more yards and collapsed in the snow.

As Menachem lay on the ground, in excruciating pain, the soldiers surrounded him and mocked him. One soldier wanted to shoot him on the spot, while another resisted the temptation. “We need them for the front lines,” the second soldier said. “Too many of these Jews have been dying. Let’s send him back to the hospital and get him patched up, so he can come back here and continue to dig trenches.”

The soldiers picked Menachem up and dropped him in a small indentation in the ground used to collect water. They did that just to torture him. They did it several times before they put him on a truck headed back to a field hospital, 10 miles from the front lines. Menachem was in pain. But he clutched his pocket where his tefillin were. When he got to the hospital, a group of soldiers took him inside. They took off his coat and set it aside, and then they dropped him into a stainless steel drum full of ice cold water. They kept laughing and making jokes.

A doctor walked into the operating room, told the soldiers to put Menachem on the table, and immediately ordered everyone out of the room.

Menachem was all stretched out on the table, sopping wet, under blinding lights. He was thinking, “I’ve been shot. I’ve been tortured twice this evening. What else can God want from me?” As he stared into the doctor’s eyes, the doctor leaned over Menachem and whispered in his ear: “I am a Jew. I never had a bris. I will take care of you.” Menachem was speechless. The doctor removed the bullet, stitched Menachem up, and said, “You are super thin. I’m going to order that they put you to work in the kitchen and you must eat everything you can lay your hands on so that you can fatten yourself up.” This was music to Menachem’s ears.

Shortly after Menachem started to work in the kitchen, the doctor told him that in a week or two he would be transferred to another field hospital. “Once I am gone, you must take a knife or utensil and open your wound so it starts bleeding heavily again,” the doctor told Menachem. “This will save you from going back to the front lines where I am told the battles are becoming more intense.”

Shortly after Menachem started to work in the kitchen, the doctor told him that in a week or two he would be transferred to another field hospital. “Once I am gone, you must take a knife or utensil and open your wound so it starts bleeding heavily again,” the doctor told Menachem. “This will save you from going back to the front lines where I am told the battles are becoming more intense.”

Menachem reopened his wounds and the new doctor declared him unfit to return back to the front. Weeks later, word spread within the hospital that the Russians had killed all the soldiers and prisoners on the front lines. In the end, my father’s life was saved by that bullet in his leg.

Some time later, all the prisoners at the remote base in Russia where Menachem was held were told, “You are free to go.” Menachem and two other prisoners thought that the near-by mountains and forests would be a safe place to hide. As they got deeper and deeper into the forest, one of them noticed a cave in the mountain, partially hidden by trees. They climbed in and stayed there for several days, slowly eating the small amount of food they had brought with them.

The war soon ended and Menachem was finally free.

My father walked from the Russian frontier back home to Hungary. He begged for food, knocking on doors and saying in Russian, “I am a refugee. Please help me with some scraps of food, or even a raw potato.” He slept in the streets, or in open fields. But still he held onto the hope that with of God’s help he would make it back to his hometown of Nyirbator.

Three and a half months later, Menachem arrived, only to find that gentiles were living in the house where he, his parents, and his 10 siblings had lived. Not knowing what to do, he wandered around town and came across two friends. They hugged and kissed each other, with joy and tears.

With Hungary in a state of chaos, they broke into the police station and made it their temporary home.

Upset that the Jewish homes were occupied by gentiles, the three friends devised a plan. With Hungary still in a state of chaos, they broke into the padlocked police station, where they found badges, handcuffs, and – to their amazement – guns. They tried out all the keys to the jail cells, spruced up their appearances, had a nice meal, and made the police station their temporary home. Menachem was happy and thankful to have survived, but he was not in his own home yet, and he had no idea where the rest of his family was.

The next morning, the three self-appointed detectives went door to door and politely asked the squatters to vacate the premises. If they declined to leave, the three friends opened their coats to show their weapons. If the squatters insisted on staying in the house they had taken over illegally, they were forcefully handcuffed and whisked away to jail.

The three friends got their homes back, but their parents and siblings had not returned home from the war. Menachem closed the shades every morning before he prayed with his tefillin, the same tefillin that accompanied him and gave him comfort and hope throughout the war. He prayed that his parents and siblings would return home every day. and found a measure of comfort. Menachem and his buddies continued to evict and arrest people in town, and he wondered what he would do to put some normalcy back in his life.

One day, one of Menachem’s brothers returned from the war, then another came back, and then another. The town and its houses were filling up. After several weeks, four brothers were back home. The other seven siblings and their parents never were seen again.

One day back at the police station, as Menachem was cleaning his gun, it went off accidently, nearly killing one of his best friends. Menachem saw this as a message from God that it was time to pick a real profession. So he become an apprentice glassier, which gave him skills as well as the opportunity to work outdoors

Menachem became an apprentice glassier. One Friday afternoon Menachem was called to fix a glass door for the Gruenbergers, a family he'd known before the war and who had survived Auschwitz. When Menachem arrived, their daughter Leah was cooking the Shabbos meals. She knew that Menachem and his brothers were living without parents, and invited them for a Shabbos meal.

Menachem became an apprentice glassier. One Friday afternoon Menachem was called to fix a glass door for the Gruenbergers, a family he'd known before the war and who had survived Auschwitz. When Menachem arrived, their daughter Leah was cooking the Shabbos meals. She knew that Menachem and his brothers were living without parents, and invited them for a Shabbos meal.

Before long, Menachem and Leah were married in the living room of her home.

Menachem and Leah had two boys, and life went on as normally as possible. The entire family escaped from Hungary in 1956. First they went to Vienna, where they got the papers that allowed them to enter the United States in 1957.

My father was a man of courage and compassion toward others, regardless of who you were. He made everyone feel important. He never made a lot of money, but was always happy with what God provided him and his family. He never envied those who had more and always taught us to care for those who have less.

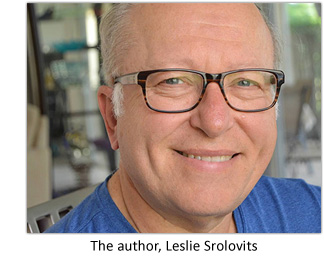

My father passed away 13 years ago, at the age of 89, and not a day goes by without my thinking of him and what he had to endure. I often wonder how a human being can go through so much, yet continue to raise a family and always have a smile on his face.

The tefillin are now in my possession and they remind me daily of who my father was, what he stood for, and how I can strive to be more like him. God willing, I will give them to my grandson Jonah for his bar mitzvah. That pair of tefillin, with all its history, will be passed to the great-grandson of Menachem Zev Ben Chaim Srolovits, of blessed memory.