An Open Letter to University Presidents

An Open Letter to University Presidents

18 min read

When does, “I have to live my own life” become selfishness?

I loved my parents, but of course I had to live my own life.

My parents were from the “Us Generation.” In that long-ago era, adult children lived at home until they married. They worked, and handed over their earnings to the family coffers. Irving Levinsky, who would become my father, was a pharmacist. He owned a drugstore in Camden, New Jersey. What he made paid the rent and the bills for his Russian immigrant parents, his younger brother Harry, who was in law school, and his two younger sisters, Sadie and Mamie, until they finished college and got married.

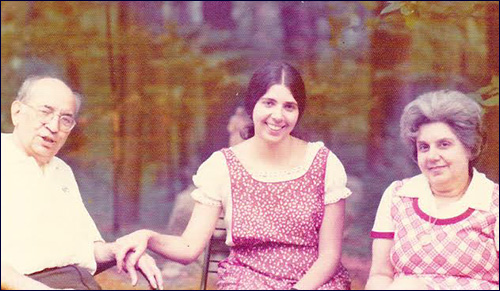

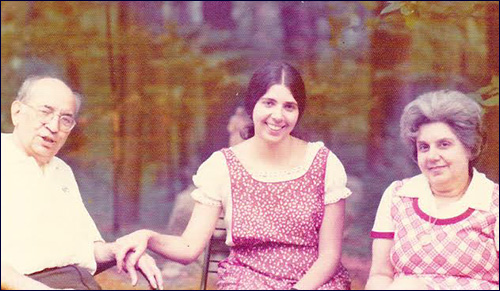

Levinsky Family taken during my ashram years (1982)

Levinsky Family taken during my ashram years (1982)

Both my parents came of age at the onset of the Great Depression. Of course, most young adults were not so selfish as to get married during the Depression. Marriage meant renting your own apartment, buying your own beds and icebox and stove, and ceasing to contribute to the family’s meager income. It was like jumping ship to your own private lifeboat in the middle of a storm, when your job was to keep the Family Ship afloat.

My mother, Leah Lintz, was a secretary for the Philadelphia school system. During the Depression, she was paid in scrip, a substitute for money. With scrip she supported herself and her widowed mother in a modest apartment in Philadelphia.

When the Depression was finally over and World War II was boosting the economy, my parents got married. For a year they lived in a cozy apartment across the Delaware River from Philadelphia, but Leah considered it too far away from her mother. So Irv bought a four-plex on Kaighn Avenue in Camden. He and Leah, soon joined by my brother Joe and me, lived in the downstairs apartment on the right side; my Aunt Mamie, Uncle Toots, and their two children lived in the downstairs apartment on the left side; my maternal grandmother Nana lived in the apartment above us; and my paternal grandmother, Grandmom, with my unmarried Uncle Harry, lived in the apartment above Aunt Mamie.

When I was nine years old, in 1957, my parents joined the migration to the suburbs. My father hired an architect and planned a ranch type house, with an apartment on top for Nana. Before construction began, however, Nana’s Parkinson’s disease debilitated her beyond being able to climb steps. So my father had the architect redesign the house with Nana’s bedroom on the ground floor.

As for Grandmom Levinsky, she moved into a suburban high rise, and Aunt Sadie moved into the apartment across the hall, so that she could look in on Grandmom several times a day. My father, after a long work day in the drug store, stopped by to visit his mother three days a week. He paid for Grandmom’s two-bedroom apartment and, when she later needed it, full-time help.

Lacking the medication that would later be developed for Parkinson’s disease, Nana degenerated quickly. She couldn’t dress or bathe herself, or get up out of bed or a chair by herself. Also, her senility had her asking the same silly questions over and over. My mother, patiently and lovingly, took care of her mother. When people would suggest that she put Nana into a nursing home, my mother would recoil as if someone had suggested that she put her children into a “very clean, well-kept” orphanage. To my mother’s mind and heart, parents, like children, belonged at home.

The same selfless devotion my parents showed to the generation above them they showed to the generation below them. My father worked 12-hour days in his drugstore to send my brother and me to expensive private colleges. When fake fur coats came into style in the sixties, my mother took me to Wannamaker’s in Philly and bought me an expensive fake fur, while she herself wore a cloth coat older than I was.

My parents wanted a daughter who would become a lawyer or psychologist, marry a nice Jewish boy, settle down a few miles from home, and give them grandchildren. They deserved such a daughter. But instead, they got me.

I admired and appreciated my parents, but for my own life I chose a different template. When it was time for me to go to college, I was accepted at the University of Pennsylvania, just 50 minutes from our house. Both Aunt Mamie’s daughter and Aunt Sadie’s daughter had graduated from U. of P. Right out of college, they had married local Jewish boys, chosen their china patterns, and set up house within ten miles of their parents. My father offered me my own red convertible if I would live at home and go to U. of P.

Brandeis was a 300-mile journey from home, but in terms of values and ideals, it was in a different galaxy.

I spurned the offer. I craved independence, which meant distance, which meant going to Brandeis, outside of Boston. Brandeis was a 300-mile journey from home, but in terms of values and ideals, it was in a different galaxy.

It was the heyday of the Sixties: radical leftist politics, pot, and every kind of experimentation dominated the campus. Suddenly my parents were hopelessly old-fashioned. I called them once a week, and visited them on college vacations, but from then on my life choices were based on what was right for me; they no longer figured into the equation. Just as touch-tone phones were an obvious advancement over rotary dials, so it was clear to me that living my own life was an advancement over the outmoded ethos of living for the family.

For my junior year of college, I decided to go to India with the University of Wisconsin’s College Year in India Program. It was 1968, when intercontinental contact was limited to aerograms, telegrams, and virtually inaudible telephone calls transmitted by underwater cables. My desire to travel to India wrestled in my heart with a deep fear: My father, who was 65, came from a family of weak hearts. His father had died of a heart attack at 62, his brother Harry at 42. What if my beloved father had a heart attack while I was in faraway India? How long would it take me to get the news? How many days would it take me to reach his bedside? One night while at the Program’s six-week orientation in Michigan, I dreamed that my father died while I was in India. I woke up vomiting.

The Program provided a psychologist. I confided in her my conflict: my filial love versus my travel lust. In the end, my travel lust won out.

In India, in a remote and exquisite jewel of a place called Bandadara, I had a spiritual awakening. From that day on, the goal of my life became God-consciousness or Enlightenment. I found a guru, meditated three times a day, and ditched my plans to go to Psych Grad School.

At my father’s insistence, I returned to Brandeis and finished my degree. My parents, of course, came up to Boston for my college graduation, which was on a Sunday. My plan was to pack up my apartment and on Thursday drive home in the Chevy Camaro my father had given me. I intended to live at home and look for a job in journalism. My parents, who drove back to New Jersey on Sunday afternoon, did not mask their joy that I would be returning to the embrace of the family.

A community of spiritual seekers had renounced everything to achieve awareness of God.

Me with my guru Mataji

Me with my guru Mataji

On Monday, however, my life took a sharp turn in the opposite direction. I decided to take a drive down to Cape Cod, and on the way stop at an ashram that a Reconstructionist rabbi had told me about. On 21 acres of idyllic woodland, the ashram and its small monastic community were presided over by an Indian guru, a 64-year-old Bengali woman called, “Mataji.” I arrived in time to join the midday meditation, held outside under the trees. The ethereal atmosphere and serenity of the ashram was reminiscent of what I had loved in India. Here was an enlightened guru and a community of spiritual seekers who had renounced everything in order to achieve the goal I cherished: God-consciousness. I requested to stay for the summer and ended up staying for fifteen years.

My parents with me at the ashram (1975)

My parents with me at the ashram (1975)

My parents, staunch Conservative Jews, were devastated, but I knew I had to live my own life. They came to the ashram for a week’s visit, and were forced to admit that it was not the free-for-all commune they had imagined. The ashram was clean and orderly; Mataji was warm and welcoming; and the community showed my parents such consideration that it was hard, actually impossible, for them to hate their dream-buster. Their opposition melted into resignation.

We settled into a rhythm where I went home for a week twice a year, at Rosh Hashana and Passover, and they came up for a week’s visit once a year. My mother’s motto became: “When you hang long enough, you get used to hanging.”

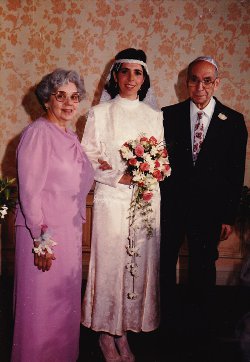

At the age of 37, I came to Jerusalem, started studying Judaism, and became Torah observant. When I was almost 39, my 77-year-old mother and my 83-year-old father finally escorted me to the huppah. My husband Leib Yaacov, a musician from California, was a nice Jewish boy from a good, middle-class Jewish family whom my parents resonated with. Fourteen months later, I gave them a grandchild, a baby girl we named Pliyah Esther.

At my wedding (1987)

At my wedding (1987)

It seemed that our dreams had finally converged. But now we were separated not by a religious ideology, but by a physical ocean. In those years before email and Skype, we made weekly phone calls and took videos of the baby on VHS tapes with a video camera as big as a typewriter that weighed as much as a watermelon. We sent the video tapes by post, and a couple weeks later my parents got to see their grandchild turning over for the first time or saying her first words.

My parents couldn’t understand why, as Orthodox Jews, we couldn’t live in New York. For me, living in the holy atmosphere of Jerusalem’s Old City and praying at the Kotel [Western Wall] was oxygen for my spiritual soul. From my parents’ point of view, it was candy.

My parents traveled to Israel every year to see us, schlepping Fisher-Price baby equipment and Star-Kist tuna that we couldn’t get in Israel. When my friends told me that their parents were “too old” to come to Israel, I scoffed. Even at 85, with painful arthritis, my father’s undauntable devotion, more than El Al, carried him across the ocean. And once a year my parents, together with my in-laws, sent tickets for us to come to America.

At 3 AM Wednesday night, February 7, 1990, I was awakened by the phone call I had dreaded all my life. My brother Joe, an emergency room doctor in New Jersey, was crying into the phone. Dad, at age 86, had gone into the hospital for stomach surgery to remove scar tissue from an ulcer operation three decades before. Something had gone wrong. “Dad’s gone septic,” my brother cried. Three hours later, with my two-year-old Pliyah, I was on a plane to New York.

“Dad’s gone septic,” my brother cried. Three hours later, with my two-year-old Pliyah, I was on a plane to New York.

For the next five excruciating weeks, my father, unconscious and hooked up to wires and tubes in the I.C.U., lingered. Every day I drove my mother to the hospital. Every day I stood by my father’s bed, reciting psalms and praying. At the end of February, my husband Leib Yaacov flew in to be with us.

My parents with Pliyah (1988)

My parents with Pliyah (1988)

At that point his parents in Los Angeles made what would be a fateful decision. Their 50th wedding anniversary was coming up in May, and they were planning a big party, inviting relatives from all over the country. They decided that since Leib and Pliyah and I were already in America, why not have the party in March?

But dare I leave my father for five days to go to L.A.? I begged his doctors to give me a prognosis. Would my father, already five weeks with no change in his condition, maintain the status quo? My ultimate nightmare, the nightmare that had plagued me since India many years before, was that he would die while I was far away. I desperately wanted to be with him when he made the transition from this world to the next.

The doctors declined to offer predictions. I flew to Los Angeles. Twenty-four hours later, my father’s kidneys started to fail. The next morning he died. And I knew, amidst tears that threatened to drown me, that my father, who had always longed to have me near, had stayed in this world as long as I was finally, finally beside him. When I left for Los Angeles, his desperate clinging to life let go its hold.

With my father’s death, my mother, who had lived to take care of him, lost her raison d’etre. On the last day of sitting shiva, after six traumatic weeks in America, I hurried back to Israel, the last reservation we could get before Passover. But I assured my mother that we would send her a ticket to come to be with us that summer.

That summer, however, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. Tensions in the Middle East skyrocketed, as the U.S. threatened Iraq, and Iraq threatened Israel. Of course, my mother was not coming to Israel during a war, and I was not leaving Israel during a war. While we stood in line to get our gas masks and bought plastic sheeting and tape to make our sealed room, the countdown to war stretched into months.

Finally in January, America attacked Iraq. The Gulf War lasted until March. By April, it seemed safe to book my mother a ticket to come to Israel in July. Strangely, throughout my life, even in India, I had never gone more than a year without seeing my parents, and now, when my mother needed me most, seventeen months elapsed without my seeing her.

My mother, depressed, spent the month of July with us in Jerusalem. I begged and cajoled her to come and live with us, but, at 80 years old and bereft of my father, she had neither the energy nor the interest in starting life over again in a foreign country. She said she would think about it as, sitting in a wheelchair, the airline attendant wheeled her away for her flight back to America.

At the end of August, my brother Joe phoned me, and announced that Mom had stomach cancer. Amidst uncontrollable sobs, I asked him how long she had to live. He answered, “She’ll definitely be here for Rosh Hashanah. She’ll definitely not be here for Passover. And she may or may not be here for Hannukah.”

Joe paid for Leib, Pliyah, and me to come to be with Mom for Rosh Hashanah. I took her to the oncologist and asked him when I should plan on coming back to America to take care of her. He replied that she had three to six months to live. I would do well to come back in a couple months.

Pliyah with my mother 2 weeks before her death

Pliyah with my mother 2 weeks before her death

On Rosh Hashanah, my cousin Dorothy asked me why I was leaving. Obviously, she didn’t understand that I could not spend Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the year, in America. What, I should pray in the local synagogue where the congregants chatted throughout the service, rather than in the sublime sanctity of my Jerusalem shul? And how was I supposed to spend Sukkot in suburban New Jersey? I didn’t even know anyone there who had a Sukkah. I reassured Dorothy that I would come back in plenty of time to take care of my mother when she needed me.

For the next two decades, I would be haunted by that look.

Throughout our entire 9-day visit, my mother looked at me in a way I could not interpret. Was it pain? Disappointment? Anger? When I asked her what was wrong, she would answer, “Nothing.” For the “Us Generation,” exploring feelings or discussing relationships was as strange an occupation as jogging. Her love was in her actions, not her words. For the next two decades, I would be haunted by that look.

Two days after Rosh Hashanah, Leib, Pliyah, and I returned to Jerusalem. My brother Joe, who was separated from his wife, moved in with our mother. Two weeks later, during Sukkot, Joe called me and told me that Mom was not getting dressed in the morning. I immediately phoned her and asked why not. She replied, “I have no one to help me get dressed.”

I told her that I would come right after Sukkot. Then I phoned my travel agent, a religious woman who worked out of her home, and asked her to book me a flight the day after the holiday. All the flights from Israel to New York were booked solid for a week after Sukkot, she told me. Then she added, “But if your mother is sick, what are you waiting for? Why don’t you go today?”

Of course she was right. I booked a flight for that night. When I called my mother to tell her I was coming, there was no answer. I tried again in an hour, then in another hour. Where could she be? Finally, I reached my brother in the emergency room where he worked. He told me that my mother had had an angina attack, and had called an ambulance. She was in the local hospital. In that pre-cellphone era, he didn’t know the number of the phone by her hospital bed, but he intended to go there right after he finished his shift. He promised to tell her that I was coming to be with her that night.

I threw into my suitcase Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’s book On Death and Dying, and clothes to last for months. I was a good daughter. I would take care of my mother till the end.

In the hustle and bustle of the airport, Batya told me: “Your mother is dead.”

Waiting for my flight at Ben Gurion airport, I was surprised to hear my name paged. I walked to the nearest paging phone. The operator conveyed the message to call my friend Batya immediately. Standing there in the hustle and bustle of the airport, I listened to Batya’s flat-tone voice tell me: “Your mother is dead.”

For the next 23 years, I lived with the piercing guilt of knowing that I had made a bad choice. I should have stayed with my mother, even at the cost of missing Yom Kippur and Sukkot in Jerusalem. Little Ms. Spiritual, I had spent so many years in the Land of “I Have to Live My Own Life,” that I had not noticed when I crossed the border into the Land of Selfishness.

Every year on Yom Kippur, when we hit our hearts while confessing our sins, when I reached, “For the sin I have committed before You by scorning parents…” I would burst into inconsolable tears.

This year, two days after Rosh Hashanah, my brother Joe called me. He cried into the telephone as he told me that he had been hospitalized with serious heart problems. He was afraid of dying. I tried to encourage him but, as a doctor, he recognized how grave his condition was.

When I hung up the phone, I knew, with perfect clarity, what I had to do. I booked a flight to America leaving in four hours. I told my husband that I would be gone for Yom Kippur, and possibly for Sukkot. I cancelled my professional commitments and packed in fifteen minutes. My husband drove me to the airport, and by 11 a.m. the next morning I was in Philadelphia, standing by my brother’s bed in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit.

I spent four to five hours a day sitting with my brother, as he slowly came out of heart failure. On Yom Kippur, I prayed at the local Orthodox shul. It wasn’t Jerusalem, but when I reached the words, “For the sin I have committed before You by scorning parents…” for the first time in 23 years, I shed no tears.

That’s when I knew I had finally rectified my transgression against my parents. I had put my brother’s welfare over my own spiritual preferences. God had given me a second chance, and I had exited the Land of Selfishness into the wider world of putting family first.