Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

5 min read

Deciding to keep kosher really meant grappling with one meaty addiction.

For anyone contemplating the laws of kashrut, the decision is inevitably reduced to a crude culinary arithmetic. Consider parting with treyf, and, soon enough, you’ll find yourself mentally dividing everything edible into three groups.

In the first, entitled “Food I’m not likely to miss,” I put shrimp cocktail and fried calamari and ham sandwiches, all of which I have always enjoyed but none of which, I realized, I would ever miss if I resolved to no longer be a few cheeseburgers removed from the faith of my fathers.

Speaking of cheeseburgers, I put them in group No. 2, “Food I’m somewhat likely to miss,” together with the oysters I enjoyed slurping with my dry martinis and the lobster I loved drowning in butter on breezy summer evenings with my family on Cape Cod.

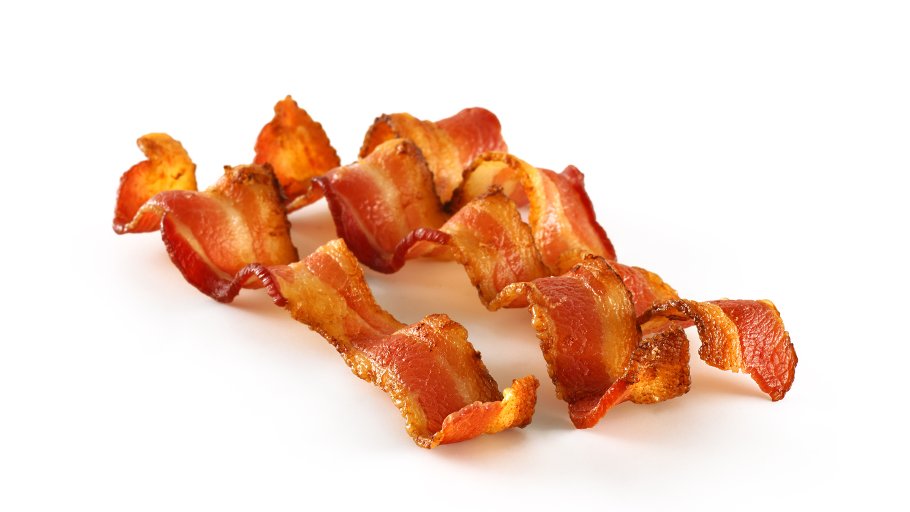

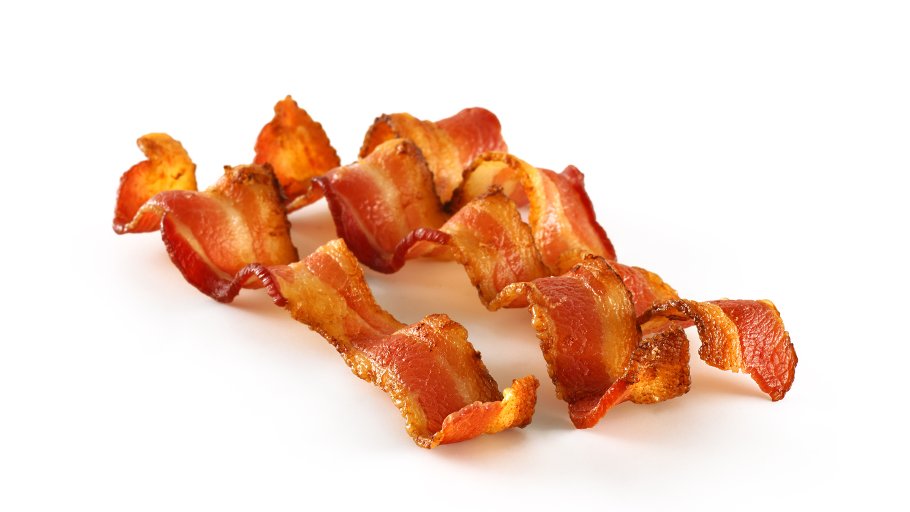

But group No. 3, reserved for food I could absolutely not imagine living without, contained one single entry: bacon.

It was, after all, my original sin, the instrument of my fall from grace. I had spent the first decade and a half of my life blissfully unaware of its scent or its taste, raised in a kosher home in Israel where a good cholent was the peak of fleshy goodness. And then, one day, slogging through puberty, I slouched into a friend’s home and smelled something transcendent. I understood, with that one whiff, what it must’ve been like to stand in the ancient Temple and take in the smoke rising from the burnt offering, every breath making clearer the spiritual affinities between meat and the divine. I asked my friend’s mother what she was making, and she replied it was bacon. She might as well have said Kryptonite: Bacon was a substance I never imagined actually existed on the same planet I myself inhabited. She asked me if I wanted a strip. Without thinking, I said that I did.

Reader, I loved it. The appeal was more than gustatory; it was emotional. Eating bacon was like taking communion in a religion of my choosing, casting off the yoke of tradition my parents placed on my back without my comprehension or consent. I still believed in God, still felt deeply Jewish, was still proud of my heritage, but with every crispy, fatty bite I felt I was forging my own path forward, a path that didn’t require me to forgo life’s pleasures to pledge my allegiance to my people and my faith.

I delivered a version of this sermon often, frequently over breakfast buffets where bacon took its rightful place beside the potatoes and next to the eggs. The days of burnt offerings, I thundered with my mouth full, were long gone; God, surely, would never have created such splendors only to prohibit us from ever enjoying them.

It’s been several swineless years now, and I miss bacon less and less every day. Meat is great, but meaning is better.

Each bite I took was a theological tractate, because bacon, unlike all other forbidden food, wasn’t just a prohibited treat: It was a synecdoche for all of treyfdom, a metaphor for the prickly and trying relationship between God and his chosen people. I enjoyed it deliberately, mindfully. It was, I believed, the instrument of my liberation.

When I got older, when the wisdom of old ideas shone brightly, when kashrut beckoned, I hesitated for a long time, mainly because of bacon. Giving it up felt like surrender. I was never, I realized, going to rationalize my way into submission. If I was going to return to the purities of my youth, I had to just plunge in and do it.

At first, every meal was a small heartbreak, defined by the meat that wasn’t there. Was this burger really good without a strip or two on top? Was that salad really healthy without the gift of crumbled goodness? And, most importantly, was my spirit growing even as my waist trimmed down?

I got my answer one balmy afternoon as we New Yorkers often do, on the street. I was hurrying somewhere when I passed an outdoor café where a young woman had just received her order: a BLT, the very spiritual balm I had ordered on so many drunken nights. I slowed down, allowing the familiar smell to settle in my nostrils. I expected to feel jittery, angry, distressed. Instead, I felt what might’ve been the greatest calm of my life. It wasn’t the calm of comprehension: I still can’t fully articulate why I decided to once again keep kosher. It was the calm of mastery and of mystery, of knowing that my soul, responding to strange signals from the primordial past, is being called upon to do something it doesn’t yet understand but that it can still, even as it obeys higher powers, command the gullet to do its bidding.

By not eating bacon, in other words, I felt at the same time completely in charge and not at all in charge, which is about as good a description of life as you’re likely to find.

It’s been several swineless years now, and I miss bacon less and less every day. Meat is great, but meaning is better.