Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

8 min read

Malka Schaps, a world-renowned professor of mathematics, is smashing glass ceilings.

Examples abound of Orthodox Jewish women serving in advanced career positions: law, medicine and the military. Now, with her appointment as Dean of Exact Science at Israel’s Bar Ilan University, mathematician Dr. Malka Schaps is perhaps the first Orthodox woman in the world to rise to this rank at a major university.

It’s been a long road for Malka, now a 65-year-old grandmother of 17. She grew up as Mary Elizabeth Kramer in suburban Ohio, attending Christian Sunday school where she studied Bible stories and memorized the Ten Commandments.

While in seventh grade, her family switched from the Christian church that her mother preferred, to a less dogmatic Unitarian one favored by her father.

It was a harbinger of what would eventually become a total move away from Christianity.

Late in high school, Malka began a personal philosophical search.

“I was raised with a commitment to be ‘good’ – not to lie, cheat or steal,” she says. “At the same time my theological position was basically atheist. This raised the very question of: Why be good?”

Malka delved into the classic philosophers such as Descartes, Nietzsche – “looking for a ‘good reason to be good.’” When she didn’t find answers, she began to consider the possibility of religion. “Once I started thinking in those terms, it was obvious that Judaism – the root of monotheism – was a good place to start.”

Malka moved on to Swarthmore, an elite liberal arts college in Pennsylvania. Her father – a professor of American history who never got tenure – pushed her to become an academician. “In retrospect, he was trying to compensate for having been less successful in his own academic career,” she says. He was pushing me to fulfill his unfulfilled ambitions."

Malka was struck by the depth of Jewish wisdom and tools for self-discipline.

Malka’s next big step toward Judaism came during her sophomore year at college, when she served as a counselor at summer camp. Her co-counselor was Jewish. Though Malka had met many Jews before, this one was “observant.” Malka’s new friend taught her how to read Hebrew (using an Israeli Telma soup poster), took her to Friday night services, and showed her some basics of keeping kosher.

What began as a passing curiosity at summer camp, soon mushroomed into a path to Orthodox conversion.

"Jewish observance, with its wisdom and tools for self-discipline, has a depth that I never saw in other religions," she says.

While still an undergrad, Malka spent a semester doing research at a university in Kiel, Germany. It was there – under the shadow of the Holocaust – that she began to consider the idea of becoming Jewish.

“As the Passover holiday approached, I wanted to attend a Seder, which I’d never done before,” she told Aish.com. “I went looking for the Jews, and discovered there were only three left in the entire city.” She eventually connected with an Australian rabbi in the city of Hamburg who had been imported as the community mohel. He became her teacher, offering guidance on how to keep kosher and observe Shabbat.

Back at Swarthmore, Malka met a young man named David Schaps. He came from a New York Jewish family who kept kosher at home. He was becoming more observant; their paths to Judaism occurring in parallel.

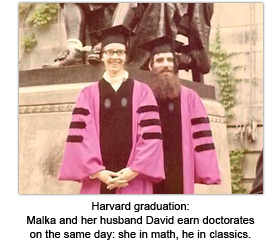

Malka converted to Judaism and married David. Together they set about pursuing PhD studies at Harvard. After a few years, they earned doctorates on the same day: she in mathematics, he in ancient Greek classics.

How did her parents react to the conversion?

“After I started keeping kosher, I came home and my mother served my favorite meal of mashed potatoes and pork chops. She was not too pleased when I wouldn’t eat it.

“She eventually got used to it. She even bought a new set of dishes so I could cook kosher at her house. Though for many years I think she hoped I would return to the Unitarian church.”

Amazingly, Malka discovered only recently that she may have Jewish blood.

“When my mother was 95, she told me that ‘back in Germany, the Kramers were Jewish.’ All these years nobody – including my father – had ever mentioned Jewish ancestry. This might explain his Unitarian background – when German Jews were ‘dropping out,’ that was a more palatable option than going full Christian.”

Following graduation from Harvard, Malka and her husband made the big move to Israel. They preferred it, she says, because “living here is like being in the center of things.”

Both Malka and David found teaching positions in Israel, but the adjustment was difficult. “It is said there is never a year of ‘working so hard and accomplishing so little’ as your first year of teaching. On top of it all, I was also trying to learn Hebrew.”

Malka and David started a family. After two children, they decided to become foster parents as well. "The other families in our apartment building had 13 children each, so we felt a need to expand.”

Two foster children stayed with the family until adulthood. Others were a rockier ride.

“We had two foster children who were siblings. At one point the parents wanted to take them back, but the kids didn’t want to go. That resulted in a long, drawn-out court case.”

On another occasion, the Schaps had a foster baby whose mother suddenly took him away and didn’t allow them to see him. “That was extremely painful,” she recounts. “For years I would go to observe him, just looking through the chain-link fence. When he was 13, I called his grandmother and she gave us permission to come visit.”

Along the way, both Malka and David both found a niche at Bar Ilan, Israel’s only religious university. He became a professor of classical studies, specializing in Greek literature and philosophy. He served for many years as chaplain in the Israel Defense Forces, and still teaches a daily Talmud class.

Malka joined the Department of Exact Sciences, encompassing to the core disciplines of mathematics, physics and chemistry. Her career flourished – she lectured at academic conferences around the world, sharing her research on “spin representations,” a futuristic quantum mechanics field that even she is hard-pressed to explain. She also founded a program in financial mathematics, which she ran for five years.

The career path was far from easy. “A professorship is not easy to attain, because you have to publish. Especially for mothers of small children, it’s hard to manage a family and a career. The challenge is simply finding the time to do everything.”

A few months ago, when it came time to choose a new dean, Malka’s name was submitted for candidacy. Initially, she resisted the idea of taking precious time away from her research. “In the end, I did it for the sake of raising the status of women. Girls are just as smart as boys and can be successful in scientific careers.”

In her “spare” time, Malka has become a prolific author of novels. Under the pen name Rachel Pomerantz, her works address many of the issues she’s confronted in her own life – particularly the idea of human bias and prejudice.

“People from different cultures have a different historical view, a different family structure, and a different set of basic premises,” she says. “It is important to account for that and not expect everyone to behave in a way that resembles your own.”

One of her most popular works examines the social divide between Israelis – religious and secular, Arabs and settlers. In researching the topic, she spent nine years as president of the prestigious alumni organization, the Harvard Club of Israel. This gave her the chance to meet with people from a variety of backgrounds and beliefs.

It’s important to speak with people – even if you don’t agree with them.

“My premise is that it’s important to speak with people – even if you don’t agree with them. When two people find a common interest, they can communicate and discover that the ‘other side’ is really human. In terms of transferring this to real life, it’s not always so easy. It requires real openness and mutual respect. It wasn’t even easy to create it in a novel!”

Is there hope for greater understanding between the various sectors of Israeli society?

“School and the workplace are the most natural places for this to happen,” she says. “At Bar Ilan, for example, people sit together in class and help each other. So it is definitely achievable."

Another of her novels revolves around two college roommates – one a woman who converted to Judaism and moved to Israel; the other who remained a secular, non-Jewish mathematician in the United States.

“These characters represent the two divergent paths my life could have taken,” Malka says.

Throughout her many years in academia, has she encountered an opposition to religion, as something that “serious intellectuals would never countenance”?

“Yes, but I always point out that the study of mathematics shares something in common with Judaism. They both seek to discern a greater order of things and the objective truth.”