Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

8 min read

Including what he considered to be his greatest day.

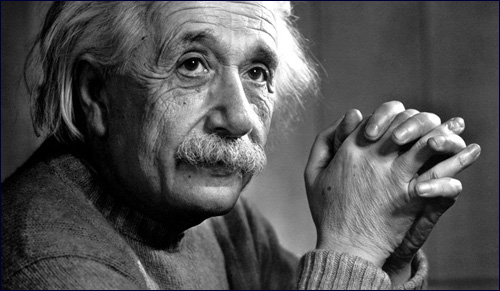

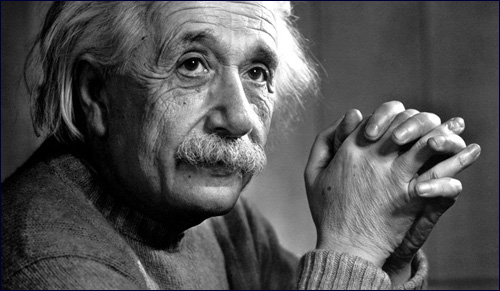

Albert Einstein is known for his famous theory of relativity, his iconic formula about the intensity of energy E=mc2, and for being one of the most brilliant scientists of all times.

Many of us know the basic outlines of Einstein’s life: he was born into a Jewish family in Germany in 1879, achieved fame at a young age for his groundbreaking work on particle physics, and fled Nazi Germany in 1933, arriving at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton in the United States where he taught until his death in 1955.

Here are ten less well-known facts about this brilliant physicist which might surprise you.

A number of myths flourish about Einstein. It’s often said that he didn’t talk until he was four and that he failed math as a child. It is true that Einstein’s language development was delayed – one nursery school teacher told his parents he’d never amount to much – but by the time he was two years old, Einstein was beginning to learn to speak, much to his family’s relief.

As for failing math, in 1935, a rabbi in Princeton, New Jersey, where Einstein was on the faculty, showed Einstein a newspaper clipping that claimed of him “Greatest Living Mathematician Failed in Mathematics.” Einstein laughed, correcting the column. “Before I was 15 I had mastered differential and integral calculus,” he explained.

Einstein’s family wasn’t religiously observant; in fact, growing up in Munich, young Einstein attended a local Catholic school. (He later recalled helping his classmates with their religion homework.) When Einstein was nine years old, however, he developed a love for Judaism. He started keeping kosher, observing Shabbat and even made up prayers that he’d sing on his way to school.

While he didn’t maintain this level of observance into adulthood, Einstein always was proud of being Jewish. In 1933, one month after Hitler was elected Chancellor of Germany, Albert Einstein and his wife Elsa left Germany for good.

Einstein’s parents continued a long-standing Jewish custom of inviting a poor student for a meal each week. When Einstein was a young child, his family hosted a Jewish medical student named Max Talmud for dinner each Thursday.

It was Max Talmud who first introduced Albert Einstein to science books, of which there were none in his parents’ home. The ten-year old Einstein devoured works by Charles Darwin, raced through the five-volume classic series “The Cosmos – Attempt at a Description of the Physical World” by Alexander von Humboldt, and read the twenty volume popular “Science for the People” series by Aaron Bernstein. Albert’s lifelong love of science was born.

Einstein travelled to Switzerland for college, where he attended the Zurich Polytechnic. The only woman in his physics classes was a young Serbian woman named Mileva Maric. They married in 1903, when Einstein was 23. Their union was unhappy and Albert soon offered Mileva an unusual bargain: if he ever won the Nobel Prize, Albert promised her he’d give her all the prize money. In return, he asked for a divorce. Mileva thought it over for a week, then agreed.

Years later, in 1921, Einstein won the Nobel Prize in physics and turned over the prize money to Mileva.

After fleeing Nazi Germany in 1933 for the United States, Einstein took up the cause of opposing racism in the United States. He became close friends with actor Paul Robeson; together this unlikely duo formed the American Crusade to End Lynching. In 1937, when the famous Black singer Marian Anderson was turned away from a hotel room in Princeton, New Jersey, where the Einsteins lived, Einstein and his wife Elsa invited Ms. Anderson to stay with them. From then on, whenever Marian Anderson passed through Princeton, she stayed with the Einsteins.

In 1946, Einstein issued a challenge to the citizens of his adopted country: “What...can the man of good will do to combat this deeply rooted prejudice? He must have the courage to set an example by word and deed….” Throughout his life, Einstein set an example, counting Black Americans as friends, lecturing at traditionally black colleges, and speaking out against racism.

In 1921, Einstein and the chemist (and later first president of Israel) Chaim Weizmann travelled to the United States to raise funds for an audacious new plan: the establishment of a new Jewish university in the Land of Israel. “I feel an intense need to do something for this cause,” Einstein wrote to a friend.

Two years later, Einstein visited Jerusalem’s Mount Scopus, where the new university’s main campus was being built. He was invited to speak from “the lectern that has waited for you for two thousand years.” Overcome with emotion, Einstein later wrote “my heart rejoices” as Hebrew University grows.

Albert and Elsa Einstein toured the land of Israel and was mobbed everywhere he spoke. “I consider this the greatest day of my life,” Einstein announced at one venue.

After fleeing Germany in 1933, a month after Hitler’s election as Chancellor of Germany, Einstein spoke out against the barbarity of the Nazis.

Nazis circulated a pamphlet in Germany decrying the Einsteins’ flight as an act of ingratitude and deceitfully speaking out against Hitler. The pamphlet ominously finished up by describing Einstein as "unhanged" – hinting that he would be put to death were he ever to set foot back in Germany.

Einstein insisted that his scientific research and understanding enabled his belief in God, instead of undermining it.

Once, sitting at a Berlin dinner party, Einstein stunned the table with this following statement: “Try and penetrate with our limited means the secrets of nature,” Einstein told the stunned guests, “and you will find that, behind all the discernible laws and connections, there remains something subtle, intangible and inexplicable.”

Years later in Princeton he explained his persistent belief in God in simpler terms. When a sixth grader wrote to the Einstein asking if scientists prayed, he made time to write her back, noting, “Everyone who is seriously involved in the pursuit of science becomes convinced that a spirit if manifest in the laws of the Universe – a spirit vastly superior to that of man, and one in the face of which we with our modest powers must feel humble….”

Of Israel, that is. Einstein was offered the presidency of Israel, a largely ceremonial role as head of government in the Jewish state, twice. Both times, he turned down the honor.

The first time was in 1948, when Israel’s ambassador to the United States, Abba Eban, called Einstein to offer him Israel’s premiership. Einstein smiled and refused, replying, “I know a little bit about nature but hardly anything about human beings.”

He was asked again in 1952. This time Einstein wrote a formal letter, explaining he lacked the experience to help govern, and also that “advancing age” was “making increasing inroads on my strength.”

At the end of his life, Einstein became even more outspoken for Zionist and Israeli causes. At the age of 73, looking back on his life, Einstein declared that “my relationship with Jewry had become my strongest human tie once I achieved complete clarity about our precarious positions among the nations.”

On the morning of Wednesday, April 13, 1955, Einstein met with the Israeli consul to go over a televised speech he was planning to celebrate the 8th anniversary of Israel’s founding. He penned a sentence about the prospects for Israel to make peace with its Arab neighbors, then broke off. Einstein's health faltered, and he died five days later. His speech, the last words he ever wrote, remained unfinished.

Works cited include:

Bucky, Peter A. The Private Albert Einstein. In collaboration with Allen Weakland. Kansas City: Andrews and McMeel, 1992.

Dukas, Helen and Banesh Hoffmann. Albert Einstein: The Human Side. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979.

Einstein, Albert, Out of My Later Years. Secaucus, New Jersey: The Citadel Press, 1956.

Folsing, Albrecht. Albert Einstein. Translated by Ewald Osers. New York: Penguin Books, 1997.

Isaacson, Walter. Einstein: His Life and Universe. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007.

Neffe, Jurgen. Einstein. Translated by Shelley Frisch. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007.

Pais, Abraham. Einstein Lived Here. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994.