Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

5 min read

The little known story is now being told.

Life for German and Austrian Jews had become steadily more restricted ever since the Nazis were elected to power in Germany in 1933. Then on November 9, 1938, mobs ran wild in the streets of German and Austrian cities, vandalizing Jewish homes and businesses, burning synagogues and terrifying and beating up Jews.

That night, which became known as Kristallnacht, nearly 100 Jews died and hundreds of buildings were destroyed. 30,000 Jewish men were sent to concentration camps in the aftermath.

Jews scrambled to leave, but there were very few places in the world willing to take in desperate Jewish refugees. The Jewish men confined to concentration camps in 1938 were told they were free to leave - if they could find a country willing to take them in. It proved an almost impossible task.

The Jews of Britain came together to help. In 1933, with Hitler’s rise to power, a group of prominent Jews, including Anthony de Rothschild, Otto Schiff, Simon Marks (chairman of the famous department stores Marks & Spencer), and Dr. Chaim Weitzman (who later became the first President of Israel), had formed the Central British Fund for German Jewry (CBF). In the aftermath of Kristallnacht, the CBF came up with two audacious plans to rescue Jews.

The CBF brought about 10,000 Jewish children to Britain in 1938 and 1939 in a massive program that was called the “Children’s Transport”, or Kindertransport.

After the horror of Kristallnacht the British government relaxed the rules of entry of certain categories of people. Unaccompanied refugee children could enter the country, receiving a temporary travel visa, if private citizens guaranteed they would pay for each child’s education, care and eventual ticket out of the country. The CBF organized British citizens to guarantee the expenses.

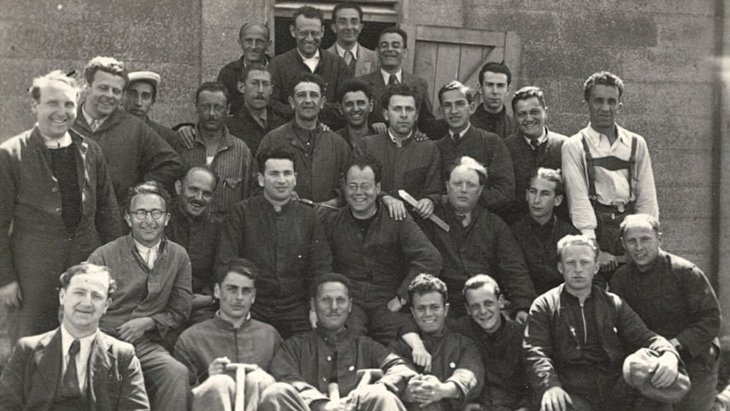

Kitchener camp, 1939. Georg Benjamin, front left. Courtesy http://www.kitchenercamp.co.uk/

Kitchener camp, 1939. Georg Benjamin, front left. Courtesy http://www.kitchenercamp.co.uk/

Some Jewish women were allowed into Britain on two year “domestic” worker visas in order to alleviate the servant shortage. (My own grandmother was among these Jewish women whose lives were saved because British households wanted a supply of cheap domestic servants.) But the 30,000 Jewish men who languished in Nazi concentration camps had no options. No country wanted them.

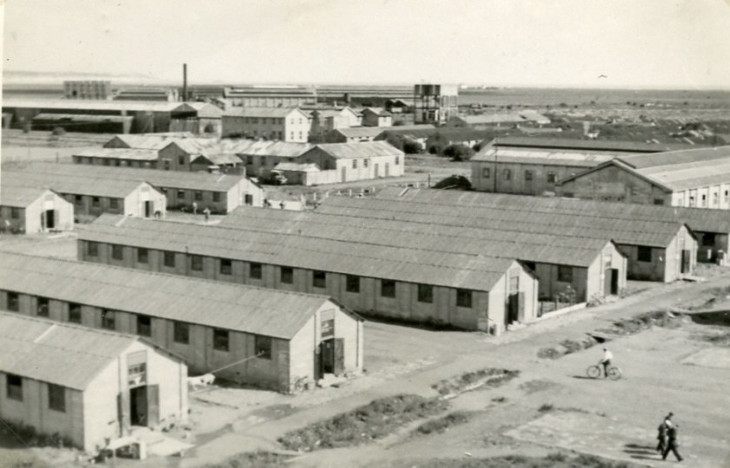

The CBF got to work, lobbying officials to take in these Jewish men. Britain’s government didn't want refugee camps on its soil. Housing German citizens, whatever their religion, was seen as particularly risky. But the CBF gained permission for a transit camp. A disused military camp called Kitchener camp in the southern English county of Kent was requisitioned to provide temporary shelter. Up to 5,000 men could be brought to Kitchener if the CBF pledged funds to support their upkeep.

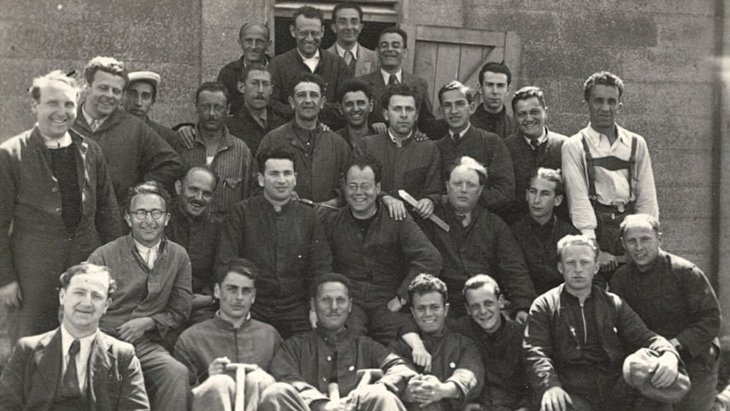

Kitchener camp, 1939, Moshe Chaim Gruenbaum, http://www.kitchenercamp.co.uk/

Kitchener camp, 1939, Moshe Chaim Gruenbaum, http://www.kitchenercamp.co.uk/

Time was short and the CBF started bringing Jewish men from concentration camps to England in February 1939. The Jewish community turned to a pair of Jewish brothers, Jonas and Phineas May, who’d previously helped run the Jewish Lads Brigade, a youth group, to run the camp. With their background in running summer camps, the CBF thought Jonas and Phineas could help welcome the traumatized Jewish men.

Lothar Nelken was a judge in Germany who’d been fired from his post for being Jewish and imprisoned in Buchenwald concentration camp. He arrived in Kitchener camp on July 13, 1939. “At around 9pm we arrived in the camp,” he recorded in his diary. “We were welcomed with jubilation…The beds are surprisingly good. One sleeps as if in a cradle.”

Eventually thousands of Jewish men called Kitchener Camp home. “It was necessary to start a system for admitting 400 men a day,” Phineas wrote on June 14, 1939.

Kitchener camp, Jack Agin, Cook, 1939. Source: Clare Ungerson’s Four Thousand men,

Kitchener camp, Jack Agin, Cook, 1939. Source: Clare Ungerson’s Four Thousand men,

with the kind permission of the Wiener Library

The camp bustled with life. Shabbat services, classes, a newspaper, several bands all occupied the camp’s swelling population. The camp also hosted weddings between the refugees and their fiancées who’d manage to make it out of Nazi Europe. The men hoped to bring their wives and children over to start new lives in England. As war became more likely, the mood in the camp plummeted. Jewish women and children left behind in Nazi Europe were in grave danger.

By September 3, 1939, when World War II was declared, about 4,000 Jewish men had been brought to Kitchener camp. With the world at war, the men realized their families wouldn’t be able to join them.

Many of the refugees were determined to fight Nazis. “Kitchener men” were allowed to join Britain’s Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps, a logistics division that helped plan British military invasions. Over 800 Kitchener refugees accompanied the British Army as they fought in northern Europe in 1940. After the evacuation of British troops from Dunkirk, the Kitchener refugees were brought back to England.

After France fell to the Nazis in 1940, the public mood changed and British authorities were uncomfortable having so many German-born men on English soil. Refugees who’d enlisted to fight were allowed to remain in the army. Other refugees were moved to internment camps, mainly on the remote Isle of Man; many of the refugees were sent to Canada and Australia. Few saw their families ever again.

For 70 years, the story of Kitchener camp was very little known. It is now being told. On September 2, 2019, a plaque was unveiled in the town of Sandwich, near the camp, marking the remarkable story of 4,000 Jewish men who were rescued. Phineas and Jonah May’s children were present, as were the descendants of some of the refugees whose lives were saved at Kitchener.

One descendent who attended was Paul Secher, whose father Otto arrived in the camp in May 1939. “My father didn’t talk about it very much,” Secher said. “I sensed it was a painful subject for him. He managed to escape (Germany) but his parents and a sister didn’t. The burden must have been immense.”