Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

9 min read

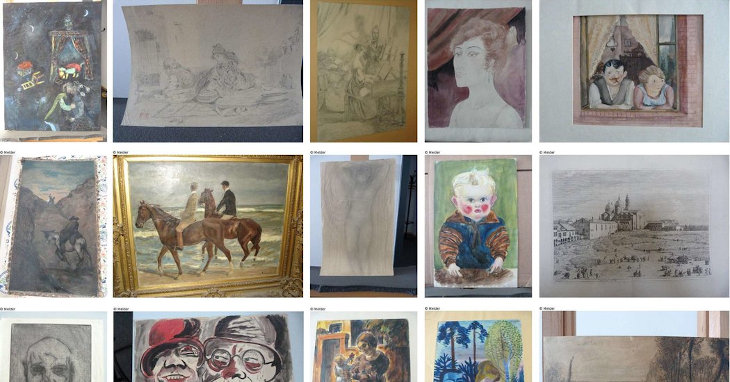

The public can finally see paintings from one of the largest Nazi-era collections of stolen art.

When German customs agents boarded the train on a September evening in 2010 they had little reason to suspect anything was amiss. The train had recently left Zurich and was crossing into Germany on its way to Munich, one of dozens of such journeys each week.

As they asked to see each passenger’s passport, one elderly German man became agitated and nervous. Alarmed, the custom agents searched his belongings and found something curious: eighteen crisp, new 500 Euro notes. Carrying this money – about 9,000 Euros, or a little more than $10,000 – wasn’t a crime, but the passenger was behaving so oddly that the agents called the police.

The passenger was Cornelius Gurlitt, a reclusive businessman living in Munich. He claimed he’d been in Switzerland in order to sell a painting, but had little documentation of the transaction. German police investigated his finances, and eventually obtained a search warrant for his small apartment. What they found rocked the global art world.

Cornelius Gurlitt

Cornelius Gurlitt

Hundreds upon hundreds of art works – by some of the most famous artists the world has ever known – were stuffed into filing cabinets and suitcases. 121 framed paintings and drawings were stacked on a shelf. A further staggering 1,258 unframed pieces were stuffed into drawers and filing cabinets. The pieces were dirty but unharmed.

Police couldn’t believe their eyes as they pulled canvas after canvas out of luggage and other spaces where they’d been crammed in the tight space. Many of the canvases bore the signatures of Renoir, Matisse, Monet, Picasso, Chagall, Durer, Delacroix, and other famous artists. The works of art were priceless. The oldest was an engraving by Albrecht Durer from the 1500s. The haul would eventually be assessed at a value of $1.35 billion.

It wasn’t hard to figure out how Mr. Gurlitt came to possess this unprecedented collection: his father, Hildebrand Gurlitt, had been one of the Third Reich’s primary art dealers, helping Nazis steal and sell hundreds of thousands of pieces of art from the 1930s through 1945. Historians believe that up to 20% of all the art in Nazi-occupied Europe was stolen by the Nazi regime and re-sold or, in some cases like Mr. Gurlitt’s, amassed in secret hordes.

Hildebrand Gurlitt

Hildebrand Gurlitt

Hildebrand Gurlitt was born in 1895 into an artistic family and became a museum director and champion of the type of avant-garde art popular in the 1920s and 1930s that would soon be labeled “degenerate” by the ascendant Nazi regime. Working first in the Konig Albert Museum in Zwickau, in the Saxony region of Germany, then at the Kunstverein Museum in Hamburg, Gurlitt’s insistence on promoting modern art by figures such as Max Pechman, George Grosz, Max Beckmann, Otto Dix and others led to his dismissal from both posts. After 1933, when he was forced out of his post in Hamburg, Gurlitt was classified as a Jew under the Nazis’ draconian racial laws; his father’s mother had been Jewish, though Gurlitt himself didn’t consider himself Jewish and was married to Helene, who was an Aryan German.

In the 1930s, the new Nazi regime began to seize “degenerate” art and force dealers to sell such art at below market prices. The Nazis had these pieces sold abroad as a way to raise money for their political activities at home. This clandestine art dealing channel was advertised as “Department IX” of the Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. Gurlitt applied for a job with the outfit and became one of four art dealers authorized to work for the Third Reich. (To guarantee no one would find out about his Jewish grandmother, Gurlitt registered his business in Helene’s name.) He pressured other art dealers to sell their art to him, often with the implicit understanding that they had no choice but to sell their collections to Gurlitt at below market rates. Many of these works were sold abroad, most often in Paris; some were kept for a museum that Hitler planned to build in the Austrian city of Linz.

Part of the Gurlitt Collection

Part of the Gurlitt Collection

Gurlitt prospered particularly at the expense of Jewish art dealers. In 1935, all German art dealers had to become members of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts, and that body began to systematically exclude Jews. Desperate, Jewish dealers found themselves selling their collections for a pittance. “When we speak about looting and art theft it normally wasn’t robbing,” explains Rein Wolfs, Director of the Bundeskunsthalle museum in Bonn. “It was a more, let’s say subtle, way of getting these works… It was mostly by suppression or by putting so much pressure on somebody that he had to sell.”

Throughout the 1930s, the Nazis seized modern art, often created by Jewish artists, from museums and private collectors, deeming the works too “degenerate” to be seen publicly. In 1937, senior Nazi official Joseph Goebbels arranged an exhibition of 650 of these stolen artworks in Munich. The exhibit attracted over two million people, including Adolf Hitler. Afterwards, the works were either destroyed or given to Gurlitt and other Nazi-approved art dealers to sell outside the country.

Soon, Hildebrand Gurlitt was distinguishing himself as one of the Nazis’ most profitable art dealers. He routinely sold Old Masters abroad, knowing that they would command the highest prices. Many works made their way into his personal collection, too. It’s hard to comprehend the scale of the looting: art historian Meike Hoffmann estimates that over 650,000 individual paintings, drawings, books, sculptures and other works were taken from museums, private collections and churches in Nazi-occupied Europe. Historian Susan Ronald notes in her book Hitler’s Art Thief; Hildebrand Gurlitt, the Nazis, and the Looting of Europe’s Treasures that by 1939 so many items were stolen that the Nazi art warehouse on Kopenikerstrasse in Berlin became one of Germany’s largest de facto art collections, with over 12,000 works. When World War II broke out in September 1939, that number swelled enormously.

After the war, Gurlitt presented himself as a victim of Nazi persecution, based on his Jewish grandmother, and was allowed to keep much of his art. He told Allied investigators that his private art collection had been destroyed in Allied air raids. In peacetime, he worked for an art collection in Western Germany called the Kunstvereins fur die Rheinlande und Westfalen, where he championed modern artists in the late 1940s and early 1950s, much as he had in the 1930s, as if the war never happened. When he died in 1956 at the age of 61, Hildebrand Gurlitt left his enormous secret art collection to his son Cornelius and his daughter Renate.

Cornelius was a reclusive figure. Nobody outside his small family knew of the priceless treasures crammed into storage areas all over the apartment he inherited from his father, until police searched his home in 2012. That same year, Renate died; when those going through her belongings found eighteen pieces of art of dubious provenance in her home, they were sent to the German Lost Art Foundation, which helps track down the owners of art that was seized in the Nazi era.

The foundation was able to find the owners of four of Renate’s works: two drawings the artist Charles-Dominique-Joseph Eisen, a painting by Augustin de Saint-Aubin, and a self-portrait by Anne Vallayer-Coster were all hanging on the walls of the Jewish Deutsch de la Meurthe family in Paris when their apartment and belongings were seized by the Nazis. One daughter, Georgette, survived the Holocaust, and was able to take possession of her family’s artwork.

In the case of Cornelius Gurlitt’s much larger collection, the German authorities did nothing for months. It was only a year later when the German magazine Focus reported on the existence of the collection that public pressure came to bear and the authorities stepped up their efforts to track down the heirs of the artwork’s original owners. In most cases, little could be done. Germany set up a special task force just to deal with the Gurlitt trove. It identified 499 works that could be proven to have been stolen by Nazis. Of these, the task force was only able to find heirs to claim four works of art. After two years, the task force announced it was dissolving; an international outcry led it to continue its work, though little changed. In many cases, it seemed too much time had passed: the original owners of the plundered artworks were dead and no heirs could be found to claim them.

Cornelius Gurlitt died in 2014 and seems to have had a change of heart before he died, desiring at last that the stolen artworks go to their rightful owners. He bequeathed the artworks to the Museum of Fine Arts in Bern, Switzerland, with the proviso that the museum continues to try and track down the pieces’ rightful owners. It has proved a difficult task, but the museum has come up with a creative way to highlight the problem of Nazi theft and to ensure that the Gurlitt Trove is seen widely. In 2017 they opened a special exhibit in Bern, as well as exhibits in Bonn and Berlin, showing some of the stolen paintings and educating museum-goers about Nazi activities.

A show is also currently underway at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. “Fateful Choices: Art from the Gurlitt Trove” shows a hundred works from the collection. The exhibit is a reminder of the fundamental way that Nazi looting changed the art world in Europe and beyond. “It sheds light on systematic looting of art by Nazi Germany,” explained Germany’s Ambassador to Israel, Susanne Wasum-Rainer, when she viewed the exhibition in Jerusalem. “The exhibit is a visible success because of the amazing cooperation across borders in the field of provenance research. It pays tribute to the families, collectors, and artists who suffered in the war.”