Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

7 min read

Life was at stake. A young Rabbi Yisrael Salanter was moved to take forceful action.

In 1848, a cholera epidemic struck Vilna, Lithuania. It was near Yom Kippur.

Two incidents have come down to us from that frightful time, one rather well known, one not. It is the lesser known incident that, I believe, speaks loudest at this time of the coronavirus.

In 2020 we have been mentally, medically and psychologically unprepared for an epidemic, let alone a pandemic. The same was true in Vilna in 1848. Leadership was called for. Rabbi Israel Salanter stepped up.

Only 38 years old at the time, he assumed spiritual authority for the physical welfare of the Jewish citizenry. He was a brilliant Talmudist, but was not a member of Vilna Beth Din and held no other communal position.

Although there are different versions of precisely what did on Yom Kippur, most versions yield this picture: He issued a halachic ruling that it was required (not permitted) to eat on Yom Kippur in order to prevent the weakening of one’s body, which would render one vulnerable to the cholera and to death. People were dying every day in Vilna. Rabbi Israel not only issued the ruling, he ate himself, in full view of the congregation. He shortened the prayers. He advised people to take walks in the fresh air.

An uproar ensued. By what authority did this young rabbi usurp the prerogative of the Beth Din of Vilna, “the Jerusalem of Lithuania”?

Rabbi Israel was unmoved. Life was at stake. His relatively young age and secondary position did not alter his course.

There are also different versions about what he did the day after Yom Kippur. One version, transmitted by Rabbi Y. Y. Weinberg, has it this way:

When called to task by the Vilna Beth Din for not consulting with it before he issued his ruling, the rabbi did not defend himself or provide his reasoning. Rather, he delivered a brilliant talmudic discourse – on a totally unrelated topic. He made his point. His knowledge was equal to that of the Beth Din. He was not to be questioned.

Parenthetically, his leadership during the cholera epidemic was the initial step that transformed him into the major figure in Jewish history that he has become.

Rabbi Israel’s act on Yom Kipppur is the more well known of his actions during the cholera epidemic. The lesser known act is this:

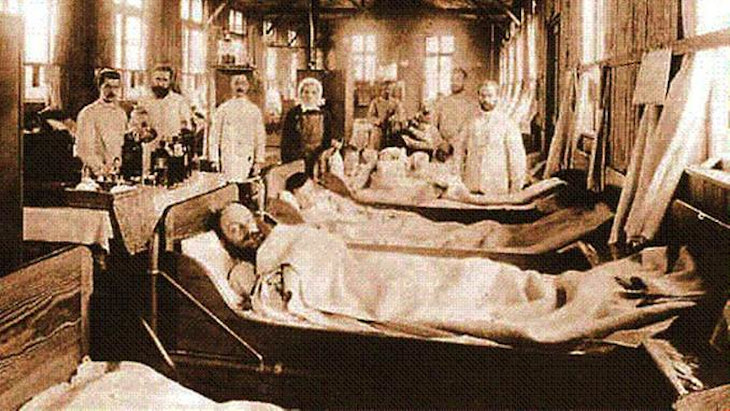

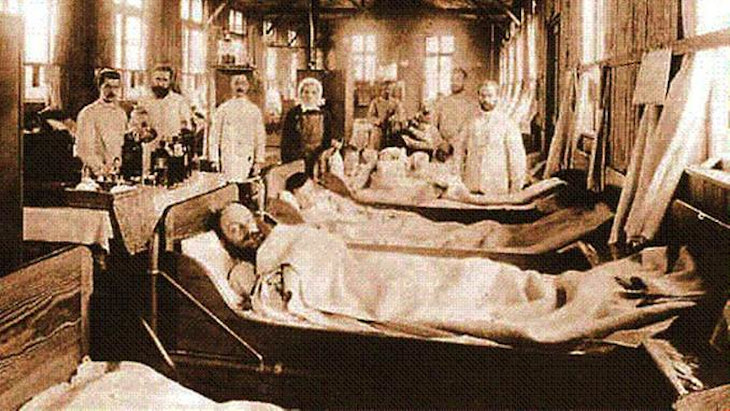

Rabbi Israel established and raised the funds for a makeshift hospital of 1,500 beds and persuaded physicians to work without pay.

Rabbi Israel established and raised the funds for a makeshift hospital of 1,500 beds and persuaded physicians to work without pay. He organized a platoon of 60-70 yeshiva students to be first responders, to provide what we would call today emergency services to those who fell ill with cholera.

Rabbi Israel was especially present on Fridays and Shabbos to make certain that his lenient rulings concerning the preparation of hot meals on Shabbos for the ill were implemented by his students, without resort to asking gentiles to step in to perform the otherwise forbidden Shabbos labors. These were obligations on Jews.

An extraordinary exchange punctuated this sequence of events. A certain elder in Vilna fell ill to cholera. Rabbi Israel’s students spared no effort to save his life, including chopping wood and boiling water for him on Shabbos. After a while, the elder got well, whereupon he came to Rabbi Israel and his committee to thank them for saving his life. He said, however, that the yeshiva students were excessive in their violation of the Shabbos laws.

Rabbi Israel, known for his extreme self-effacement and sensitivity to other’s feelings, did something no one had ever seen him do. He became outraged and yelled at the man in full view of all those present:

“You idiot! You’re going to tell me what is permitted and what is forbidden? I have taken on myself to ask 60 to 70 young people to work with the ill continually, and I promised their parents that I would keep them healthy, G-d willing, and indeed they are all healthy – not one has taken ill. Are you prepared to do this?”

The elder apologized profusely – which was not the point. The point was that Rabbi Israel could not afford to let the message get out that these young men ought not risk their patients’ health by easing up on the Sabbath violations, which, if they did, would also mean not risking their own health; and the entire project could collapse in tragic loss of life.

I regard Rabbi Israel’s triage hospital as the more challenging and meaningful of the two steps that he took, given the current coronavirus with its attendant risks undertaken by health workers, the triage hospitals in public parks, the suggestions by some that young people intentionally expose themselves to the coronavirus and (hopefully) build an immunity to it, so that they can treat others (hopefully) without risk.

Rabbi Israel’s actions raise weighty questions. How could Rabbi Israel expose his students to the ill? How could he take it upon himself to promise their parents that none of them would become ill themselves? How do we explain that reportedly none of them did fall ill? Would any rabbi do this today, during the coronavirus?

Among the possible answers:

Perhaps there is a distinction between cholera and the coronavirus, or between the conditions of contagion in a relatively small city like 19th-century Vilna and large cities today.

Perhaps Rabbi Salanter’s utter acceptance of the Torah’s demand that human life be saved, no matter what, protected him and his students. Put differently, perhaps the utter faith of the students in the supremacy of saving human life, and in the spiritual stature of their mentor, protected them.

I may be misinformed, and I hope I am, but I do not think anyone today would or could take upon himself the actions and the promise that Rabbi Israel took upon himself. We are left with the imperative to do all we can, as individuals, to protect ourselves. Analogous to our hand-washing, mask-wearing and social distancing, Rabbi Israel issued rulings for the healthy. Among them was not to eat fish, since the doctors in Vilna considered it a risk.

Rabbi Israel ruled: To eat fish is to eat pig meat. Equally forbidden.

One of the eminences of Vilna approached Rabbi Israel and asked:

“Since I always eat fish on Shabbos, and since I am healthy, may I taste soup made with fish?”

Rabbi Israel answered: “Sure. Just put some hazir (pig product) in the soup and then eat them together.”

Postscript: Writing apparently during the cholera epidemic, Rabbi Israel made these points:

Precaution is piety. Adherence to the strictures of the doctors, even if that upends normal religious practice, is itself adherence to the religion.

Bitterness is not in order. Since change in lifestyle is the proper religious response to the crisis, the change is an opportunity to serve God with joy.

Minimize mourning. In a dialectical docket of complementary values, Rabbi Israel priorities the sweetness of the fate of dead – their eternal reward – but then notes the supreme importance of mourning over the dead and the loss of the richness of this world, finally locking both values into the present moment: If someone has died from cholera, the relatives should not stress themselves by mourning overmuch, but take hold of the first value, seeing their loved one as having reached the ultimate goal: eternal life.

This article originally appeared in the Intermountain Jewish News.