Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

17 min read

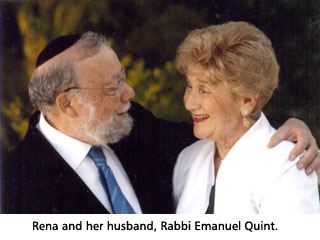

As a Holocaust survivor, Rena Quint strives to live her life to the fullest.

The following interview appears in Women Talk, Debbie Shapiro's new book of interviews and profiles of Jewish women around the world.

Rena Quint was liberated from Bergen-Belsen as a young child, with no memory of her real family. Taken away from her mother and later from her father, in the camps she had seen one adopted mother after another sent to the gas chambers, while she somehow survived the unspeakable -- a lone flame among the ashes.

The first ghetto the Germans established was in my hometown of Piotrkow. When they built a wall around the Jewish section, the Jews who already lived there were allowed to stay, so we were allowed to remain in our own home. Jews from surrounding areas were herded into the ghetto and, later on, Jews from nearby cities and towns as well. The ghetto became very, very crowded. Five or six families lived in one apartment, and there was never enough food.

My father worked in a glass factory. The Nazis used all able-bodied men and women as slave labor.

One day, the Nazis entered the ghetto and started rounding up all the Jews who were not working. They came into the houses with guns and screamed for everyone to get out. People were frightened and tried to leave all at once. There was a stampede. Everyone was crying and yelling. We were taken to a very big square. From the square we were marched to the synagogue.

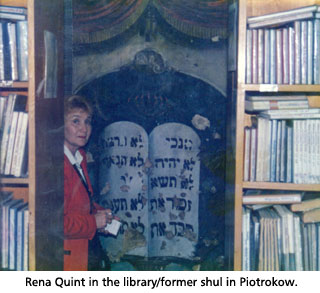

Today the synagogue is used as a library. You can still see the Magen David on it. If you ask the librarian to open a curtain, you can see the indentation where the Aron Kodesh used to be.

In the synagogue, we were crowded into two rooms, the main sanctuary and the beis medrash, which was on the floor below. I remember lots of yelling and crying -- and shooting. I must have been holding on to my mother. I was about five years old at the time.

I also remember a man standing just outside the shul door. He may have been my uncle; I really don’t know. He beckoned to me, calling me by my name, which in those days was Fredgia, and told me to run. I really don’t understand why I was willing to run or why my mother was willing to let me go. You’re a mother. Would you let your child leave you during a time of danger? Would you let your child just run away like that?

Everyone in that synagogue, including my mother and two brothers, was taken by railway cars to Treblinka.

I let go of my mother’s hand and ran out of the synagogue. Everyone in that synagogue, including my mother and two brothers, was taken by railway cars to Treblinka, where they were gassed and their bodies burned. The man who told me to run took me back to my father in the ghetto. My father hid me in a cellar.

When my father saw that it was impossible to continue hiding me, he dressed me like a boy. He cut my hair, changed my name from Fredgia to Froyim (Ephraim) and told the Germans that I was ten years old, because ten-year-old boys were considered old enough to be used as slave labor. I’m not tall now, so I couldn’t have been tall then -- but somehow I got away with it. I worked in the glass factory together with all the men.

I have very few memories of that time. I do remember waking up one morning and discovering that I was covered with pimples. It was probably chicken pox, or German measles, or some other children’s disease. At the time, I saw it as the worst thing that could ever happen to me, and was thrilled when the rash disappeared.

I also remember the German Shepherd dogs. If the Germans thought that one of the workers was slacking off in his work, they would sic a vicious dog on him. These types of things one doesn’t forget. I also remember the heat of the ovens and the men helping my father cover up for me. But I don’t remember much else. After all, I was only five years old at the time.

Eventually -- I have no idea how much later -- the Germans rounded us up and took us to the train station, together with Jews from the other factories. They loaded us onto cattle cars and we started moving. I have no idea how long we traveled. We had nothing to eat or drink the entire time. With only two pails for our needs, the car stank. People vomited. People died. People walked over each other. There was no air.

When the train finally stopped, the Nazis flung open the doors and threw the dead bodies onto the snow. The rest of us had to jump. There was snow on the ground and we used it to drink and wash our faces. As we were getting adjusted to this new situation, Germans on motorcycles with side cars drove up to where we were standing. Using loudspeakers, they announced that we were being taken to a work camp and that the men should go to one side of the train and the women to the other.

My father realized that the Germans would soon discover my disguise when we’d undress to enter the showers for disinfection. The Germans really didn’t care if we were clean or not, but they wanted to confiscate our clothes and make sure we weren’t hiding anything on our bodies. It was obvious that I couldn’t join my father in the men’s camp. My father asked a teacher that he knew if she could keep an eye on me. That woman became my new “mother.” I don’t remember the teacher’s name or what she looked like. When she was murdered, another woman took her place. Over the next few years I had several different “mothers.”

When she was murdered, another "mother" took her place.

That was the last time I saw my father. He gave me some pictures and said that after the war was over he’d meet me in Piotrokow. He didn’t live long enough to go back, and I never returned either.

Years later, I did some research and discovered that according to official German records I was in the Piotrokow Ghetto until 1943. From there I was taken to a labor camp and, later on, to Bergen-Belsen.

I remember entering Bergen-Belsen with one of the infamous death marches. Many of the people marching with me had died along the way. We were very cold and sick. I was with a woman -- one of my many “mothers” -- but I don’t have a real memory of her. I was still carrying the pictures that my father had given me. When we went into the showers, one of the guards grabbed my pictures from me and tore them up. For him, it was garbage. For me, it was my last connection with my roots.

It was probably 1944 when I arrived in Bergen-Belsen, but I really don’t know for sure. There are no records, absolutely none. Before the war ended, the Germans tried to burn everything, to hide what they had done. When the British arrived, the smell of death and infectious disease was so rampant that they burned the rest of the camp. So I can tell you when I was liberated, but I cannot tell you when I arrived.

When we woke up each morning, we’d pull the dead bodies out of our bunk and dump them outside. There were bodies everywhere. It was perfectly accepted; they were just there. As a child, I didn’t know that these were terrible and unusual things. I took it for granted and thought it was normal.

I was in a special section for women and children. One side was for mothers and their children; the other side for orphans. I was always in the side for mothers with their children because there was always someone who “adopted” me as her daughter and took care of me. We were alive because Eichmann was keeping us there to be used as bargaining chips with the Allies.

Most of the mothers and children in my section did not survive. Those who did survive looked like skeletons. The women who adopted me needed someone to love, and I needed someone to love me and take care of me, so we both benefited.

April 15, 1945, the day the British liberated Bergen-Belsen, started out like any other day. I was sitting outside under one of the trees, surrounded by corpses, positive that I’d never get out. No one ever got out of Bergen-Belsen -- they just died. When a person was incapable of sitting any longer, he’d simply lie down and die, just like that. But then something happened that had never happened before. Tanks entered the camp. People were running and shouting. The British had arrived!

When the British entered the camp, they found thousands of dead bodies everywhere.

When the British entered the camp, they found thousands of dead bodies everywhere. No one knew who they were. There was no way to identify them. To prevent the spread of disease, the British bulldozed the bodies into mass graves of 5000 corpses each.

The British tried to give the people who were still alive food, but after starving for so many years many of the inmates were not able to digest real food, and died.

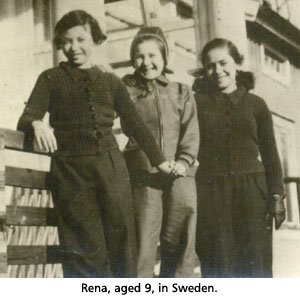

I was ill with typhus. The British brought me to a makeshift hospital, where I lay on a stretcher covered with real sheets! Later on, I was sent with a group of 6000 women and children to Sweden.

The start of a whole new stage in your life. What happened there?

In Sweden, one of the women claimed to be my relative and “adopted” me. She became my new mother. But I was so sick that I was transferred from the DP hospital to a regular Swedish hospital. There, a Christian couple wanted to raise me as their own child, but the hospital personnel explained that since I was Jewish, I belonged in Palestine. I often wonder what would have happened to me had I ended up going with that couple.

I spent one year in Sweden. There I met a woman named Anna. She had two children: a boy, Sigmund, aged fifteen and a half, and a daughter, Fanny, aged nine and a half -- my age. Anna’s brother, who had moved to the United States before the war, sent her immigration documents. But while she was preparing to travel to America, her daughter, Fanny, died. Now Anna had an extra immigration document. She asked me if I’d like to go with her to the United States and become her new daughter. She gave me her daughter’s name, birthday, and place of birth, and put my picture in her passport. In 1946 I arrived in the United States together with my new mother and brother.

Anna’s brother lived in Lindenhurst, Long Island. He and his family took care of us. They were Orthodox. But three months later, while we were vacationing in the Catskills, Anna passed away.

That must have been so painful for you.

I just accepted it. It was something that kept happening to me. I had already lost several “mothers.” It was reality. Now that she was gone, I knew that I’d have to find someone else to become close with. I knew that somehow someone would become my new mother.

The first time I ever attended a funeral was when Anna passed away. People stood around her grave and cried. No one explained to me what was happening. They thought I understood. But in Bergen-Belsen, thousands of people had died and were buried in mass graves, yet no one cried. No one mourned their passing. I couldn’t understand why everyone was making such a fuss over just one woman. It didn’t make sense to me.

Photo of the three girls

After the shivah, the family that had brought Anna to the United States decided that they couldn’t take responsibility for another child -- me. A wonderful family in Brooklyn, the Globes, invited me to their home for Shabbos. At the end of Shabbos they asked me the same question that I had been asked so many times before: Would you like to become our daughter?

Would you like to become our daughter?

Before adopting me, the Globes searched the world to find out if I had any living relatives. They discovered two cousins in Israel. But my cousins were not interested in raising me. They told my parents that life in Israel was very difficult and that I was much better off in America.

This wonderful couple, Jacob and Leah Globe, became my parents. They raised me as their daughter. They succeeded in providing me with a normal childhood. I had toys, a bicycle, a social life; I went to school; I learned to play the piano -- everything. I was their only child. They showered me with all their love.

In 1947, my adoptive parents changed my official name from Fanny, the name of the little girl who’d died, to Frances, and finally to Rena. Rena means joy -- Freidel in Yiddish. Before the war, my name had been Fredgia, which is the Polish version of Freidel.

My mother lived to be over a hundred years old. My granddaughter remarked that when she arrived in the Next World, the first people she encountered must have been my biological parents, who thanked her for raising me like her own daughter. I really had two sets of parents, each of them with their own individual role and merit.

Throughout the years, as I was growing up and later on as I raised a family, I never spoke much about the Holocaust. But in 1981, when my children were older, I attended a survivors’ gathering. After that I started doing a lot of research as I began searching for my roots.

Were you successful?

I didn’t find anyone who remembered my family. It was as if we had never existed. Then, in 1984, we made aliyah and I started volunteering in Yad Vashem. In 1989 I went to Poland with a Yad Vashem group to research my roots. I found my birth certificate and my parents’ marriage license. The marriage license provided me with a lot of information: my parents’ ages; my mother’s maiden name, Nesser; and my grandparents’ names. Through these pieces of paper I was able to make a connection with my past. I didn’t have any pictures of my biological family and I couldn’t remember what they looked like, but now I had their names.

As a Holocaust survivor, I feel impelled to live my life to the fullest. Those who didn’t survive charged those who did to tell the world what happened, so they should never forget! When I speak about the Holocaust, I am doing my part to keep it from being forgotten. We know the truth, and we must teach it to our children and grandchildren.

I often accompany groups visiting the camps in Poland as a historian and eyewitness. We usually visit Auschwitz-Birkenau, Treblinka, and Maidanek, the three main camps where Jews were murdered. We also go to Warsaw and Lublin, the site of the famous Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin.

My survival was nothing short of a miracle.

Many of the young people on these tours never realize that these people were killed solely because they were Jewish. I explain to them that my survival was nothing short of a miracle. So many things, all completely out of my control, continually occurred to make sure that I would live. Hitler tried to destroy the Jewish people. When Jews assimilate and intermarry, they are continuing Hitler’s job.

Very often, the groups that I lead are mixed, with both religious and non-religious kids. During the Shabbos meals, the religious kids start dancing, and soon the others join in. Within five minutes you can’t tell the difference: They’re all Jews. They gain a strong sense of Jewish identity. For many of these kids, this is the first step toward discovering and reconnecting with their heritage.

After touring the camps and learning so much about the Holocaust, the kids become extremely sensitive to anti-Semitism. When our groups walk the three kilometers from Auschwitz to Birkenau, we are surrounded by armed security guards who are being paid to protect us. But we are all very aware that sixty-some years ago they were there to shoot us. It’s a strange, eerie feeling.

One year, we were traveling on the freeway when there was a bad accident on the opposite lane. Since our group contained doctors and nurses, we stopped to offer medical assistance. The kids were upset. “Why should we stop?” they argued. “Maybe the guy who is injured, or the guy’s father, killed Jews during the war.” But our people got out, crossed the barrier, and helped the injured driver.

When the doctors and nurses returned to the buses, they explained, “We’re doctors. We’re Jews. We’re human beings. This is what we have to do. If the man dies, of course they will say that the Jews killed him. But if he lives, will they say that Jews saved him? Who knows? But it really doesn’t matter. We had to do the correct thing.”

We’ve had our share of anti-Semitic incidents. One time our group of seven buses -- that’s about 350 people -- was on its way to Kielce, where there had been a pogrom after the war, when we received a phone call that about 50 skinheads were waiting for us there. We decided to turn back, though the kids were very upset. They argued that we outnumbered the skinheads and could easily fight them. But that in itself was problematic. The media would focus on the fight rather than the reason we were there to begin with.

When my husband and I visited Treblinka, we were unable to locate the memorial stone for my city, Piotrokow, among the other 17,000 memorial stones there. A few years later, as I led a group of young people to the camps, before arriving in Treblinka I went to each of the buses and asked the kids to look out for Piotrokow’s memorial stone. In Treblinka, the weather was absolutely horrible, raining and simply awful. As I was standing at the place where my mother and brothers were murdered, one of the boys in the group -- a real hippie with long hair and earrings -- raced up to me and said, “Rena! Rena! I found it! I knew I would find it. I prayed that I would find it!” After he calmed down a bit, he continued, “I come from Argentina. My family knows nothing about being Jewish. No one in my family had anything to do with the Holocaust. But now that I found your stone, I am positive that I am a part of the Jewish people.” This boy found his Jewish identity in Treblinka!

On another tour, I was walking in Warsaw on Shabbos morning with a few of the other members of our group, including a very husky he-man kind of Israeli, when some Polish punks surrounded us and began taunting us with all sorts of anti-Semitic remarks. We stood very still and ignored them until eventually they got tired of making fun of us and left. After they were gone, the husky Israeli said, “They called me a Jew. I’ve never been called a Jew before. I’ve always been an Israeli. I had to come to Poland to realize that I’m a Jew, not just an Israeli ….”