Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

10 min read

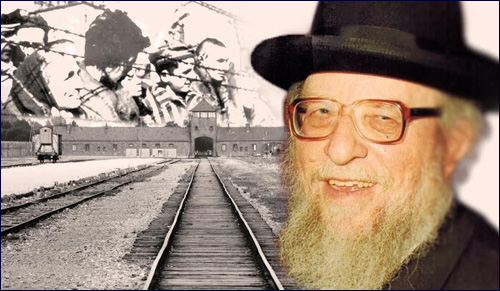

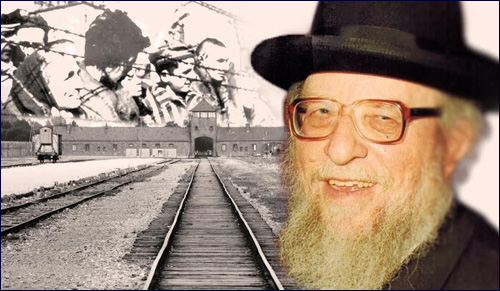

Incredible, harrowing stories from the life of a great Torah scholar.

Adapted from "Rav Gustman" (ArtScroll)

Rabbi Yisrael Zev Gustman (1908-1991) was a Talmudic genius. As a young man, he married the daughter of a top rabbi in Vilna, the center of Jewish life in the early 20th century. Rabbi Gustman's father-in-law died shortly before the wedding, thus the young 20-year-old inherited a seat on the illustrious rabbinical court of Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzinski, the head of European Jewry prior to WW2.

World War Two broke out in September 1939, with the Third Reich attacking Poland. Soon the Nazi murder machine followed the Wehrmacht, and the mass extermination of Jews at the front began. Meanwhile, pursuant to the secret treaty known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the Soviet Union invaded and took over the eastern areas of Poland and all of Lithuania.

Times became increasingly hard in Lithuania under Russian occupation. Whatever was needed was unavailable or in desperately short supply, including with winter boots. A delegation of citizens approached the Commissar (the Russian political leader of Vilna) with a desperate plea that he somehow manage to obtain boots for the city residents, without which they would be unable to withstand the bitter cold of the Lithuanian winter.

The Commissar answered them confidently. "Do not worry yourselves about this matter," he said, "The Soviet Socialist Republic, led by its great and kind father (Joseph Stalin), provides for the people!"

The Commissar was as good as his word about the boots. Within a relatively short period, by Soviet command-and-control economic standards, a locomotive entered the Vilna train station pulling boxcars filled with boots.

But there turned out to be a snafu: Upon unloading them, it turned out that the boxcars were filled with left boots only! What was to be done with thousands of left boots? No one among the Soviets had any idea what had happened. There were various theories, culminating in one question: Were there other boxcars somewhere else filled with right boots? If so, where were the missing boxcars?

Rabbi Gustman described this problem to Rabbi Chaim Ozer, who poured over railway maps in great detail. He finally pointed at a particular interchange, saying that the boxcars were there, and instructed Rabbi Gustman to go to the Commissar and inform him of the location.

If you are wrong, you will be taken out to the wall and shot for wasting our precious time with mystical nonsense during wartime.

Rabbi Gustman replied that he was aware of the short fuse of the Soviet authorities and there was a possibility that he would be treated as some kind of suspect or saboteur, and imprisoned or worse. But Rabbi Gustman relied on Rabbi Chaim Ozer's statement and proceeded to the Commissar.

The Commissar received him with all the contempt of a Communist faced with a "superstitious person" from the reactionary class of religious clerics, peddling what Karl Marx called "the opiate of the masses." The Commissar laughed at what he called the "wild guesses" of an old rabbi who could not possibly know the complexities of Soviet railway transportation. But Rabbi Gustman stood his ground, and the Commissar eventually listened.

"We will send word there to inquire about the missing boxcars," he said. "But know this: If you are wrong, you will be taken out to the wall and shot for wasting our precious time with mystical nonsense during wartime and for making a mockery of Soviet power."

Shortly thereafter, the Commissar received a telegram, and wonder of wonders! The boxcars were where Rabbi Chaim Ozer had indicated they would be, marked with the words "Destination Vilna." As a result, many of the freezing residents of Vilna received both right and left boots. From then on, the Soviet Commissar held Rabbi Gustman in high esteem, for he had divined what even Soviet Power had failed to reveal.

Rabbi Gustman related that during the entire period of the War, he recited Vidduy (the confession before death) hundreds of times, because death approached so close and so frequently. At such times he used the short form of the Viduy because he was unsure if he would be alive long enough to recite the long form.

On one occasion, the Nazis decided to "liquidate" all the Jews in a Vilna labor camp. Rabbi Gustman and other Jews were marched to the Ponary Forest outside of Vilna and lined up at the edge of a long pit. An SS man walked down the line of Jews and shot them in the head one by one, after which each one fell backwards into the pit. When the SS man came to Rabbi Gustman, he shot him in the head as well. Rabbi Gustman felt the bullet and fell into the pit as the others had, assuming he was dying.

When the SS man came to Rabbi Gustman, he shot him in the head.

But once in the pit, he found that he could move his hands and feet. He was alive! He lay still until the Nazis had finished their work, then untangled himself from all the corpses and pulled himself out of the pit. Rabbi Gustman attributes his survival in that instance to an open miracle: The bullet was actually embedded in his skull, though was invisible and no apparent wound had been inflicted.

On another occasion in the Ponary Forest, Rabbi Gustman was present when Jewish families were brought. A pit had been dug and the men were separated to stand on one side of the pit while the women and children stood on the other side. The Nazis then took the children out of their mothers' arms, flung them up in the air, then shot them while they were still in the air – after which they would fall into or be hurled into the pit. Mothers would run up to the Nazis and beg to be killed first as not to witness the death of their children.

Seeing this horrific scene, Rabbi Gustman could not hold himself back and determined to speak to the hearts of the executioners. He approached the Nazi officer in charge of the massacre and requested permission to speak to him. In response, the Nazi bashed him in the head with the butt of his rifle, and Rabbi Gustman fell to the ground bleeding from a gash in his head.

When he later lived in Jerusalem, Rabbi Gustman used to stand and watch the children march through the streets each year during the Jerusalem Day parade. He explained: "My eyes that have seen children murdered can appreciate the sight of Jewish children marching in joy through the streets of Jerusalem."

Rabbi Gustman had an only son, Meir HY"D, whom he called Meirke. He was the apple of Rabbi Gustman's eye, a boy as sweet and beautiful as any little boy one can imagine. During an Aktion against the Jewish children of the Vilna Ghetto, the SS found the improvised hiding place that Rabbi Gustman had found for 4-year-old Meirke. Rabbi Gustman lifted the boy and held him in his arms to protect him. But the Nazis beat and beat the boy as Rabbi Gustman held him, until blood flowed all over his father's body. When they were convinced the boy was dead, they pushed Rabbi Gustman and his son into a pile of manure.

Rabbi Gustman washed and buried his precious son's body himself and took off the boy's shoes, which he exchanged for bread for his starving wife and daughter. His usual procedure was to divide all the food he managed to obtain, giving the largest portion to his daughter, the next largest portion to his wife, and the smallest portion for himself. But this time, as he tried to consume his portion of bread, he found himself unable to do so; he felt he was consuming his own son's flesh, as it is written in Deuteronomy 28:53, "And you shall eat the flesh of your children."

One night Rabbi Gustman's young daughter told her father that they were starving in the Ghetto and that they should leave. Rabbi Gustman knew it was mortal danger to try to escape from the Ghetto, as many had attempted to do so and had been shot (including Rabbi Gustman's own brother). But the little girl insisted that they needed to escape. After hearing the heartfelt plea of his little daughter, Rabbi Gustman decided on the spot that they would flee.

He decided to split the small pea in half, for his wife and daughter.

The Gustmans managed to escape through a small gap in the fence without being seen by the Nazis. They walked along the side of the road, reaching the forest near Vilna. Shortly afterwards the Nazis "liquidated" the Ghetto of Vilna, slaughtering the Jews still clinging to life there. They had escaped before the ultimate catastrophe.

Once while hiding in the forest, Rabbi Gustman found a single pea without the peapod and had a question about how to divide it between himself, his wife, and his daughter, all of whom were suffering from hunger pangs. He ultimately decided to divide the single pea into two halves and gave one half to his wife and the other half to his daughter, foregoing his own share. From this episode and others like it, Rabbi Gustman would say that he learned the value of food.

When Rabbi Gustman reached the forest, his plan was to become a partisan to fight against the Nazis and defend himself and his family. However, to be accepted as a partisan, there was a single condition: A person had to come with a weapon.

Rabbi Gustman's opportunity came when he saw a lone Nazi soldier passing through a quiet place in the forest. Rabbi Gustman jumped the soldier, threw his rifle as far as away as he could, and killed the soldier with his bare hands. Years later Rabbi Gustman would look down at his hands and say, "I fulfilled the mitzvah of killing Amalek with my bare hands."

At times when the partisans were hiding deep in the forest from the Wehrmacht, with food and water extremely scarce, the partisans lips were so parched and their tongues so heavy that they lost the ability to speak. In order to be able to communicate when necessary, the partisans were forced to rub bird droppings on their mouth, in that way regaining the minimum ability to speak.

Prior to the war, Rabbi Gustman was once traveling outside Vilna with his teacher, the sagely Rabbi Chaim Ozer. Rabbi Chaim Ozer pointed out a cave and said, "Remember this cave." Rabbi Gustman had no idea why.

Further en route, Rabbi Chaim Ozer spent a great deal of time pointing out to Rabbi Gustman various plants, explaining which types were good to eat and which were poisonous. At the time, Rabbi Gustman was puzzled: What made Rabbi Chaim Ozer – whose sole pursuit was Torah study – spend his time on a lesson in botany?

Further en route, Rabbi Chaim Ozer spent a great deal of time pointing out to Rabbi Gustman various plants, explaining which types were good to eat and which were poisonous. At the time, Rabbi Gustman was puzzled: What made Rabbi Chaim Ozer – whose sole pursuit was Torah study – spend his time on a lesson in botany?

In gratitude toward the plants which saved his life, Rabbi Gustman personally served as gardener at the yeshiva.

During the war years, as Rabbi Gustman and his family hid from the Nazis in the forest, they were dependent on whatever wild plants he could gather for nourishment. He then understood the importance of that lesson – and credited Rabbi Chaim Ozer with prophetic foresight in instructing him on techniques of wilderness survival.

After the war, Rabbi Gustman lived in America, and eventually made his way to Jerusalem where he headed a prominent yeshiva. Till the end of his days, as a mark of gratitude toward the plants to which he owed his life, Rabbi Gustman personally served as gardener of the yeshiva building in Jerusalem.

After the war, Rabbi Gustman lived in America, and eventually made his way to Jerusalem where he headed a prominent yeshiva. Till the end of his days, as a mark of gratitude toward the plants to which he owed his life, Rabbi Gustman personally served as gardener of the yeshiva building in Jerusalem.

Adapted from "Rav Gustman" (ArtScroll)